Rt. Hon. Sir William Alexander and Isabella Hankey

Fact File

Sir William ALEXANDER (1755-1842)

Sir William ALEXANDER (1755-1842)

The Right Honourable Sir William Alexander was a distinguished Scottish jurist whose long career placed him among the most respected legal figures of late Georgian and early Victorian Britain. Born in Edinburgh on 18 May 1755, he was the eldest son of William Alexander (1729–1819) and Christine Aitchison, and heir to a family deeply embedded in Scotland’s civic and political life.

His paternal grandfather, also William Alexander, had served with distinction as Lord Provost of Edinburgh between 1752 and 1754 and later represented the city in Parliament from 1755 to 1761. This lineage situated Sir William within a tradition of public service that shaped both his ambitions and his sense of duty.

He was raised in a large family that included numerous brothers and sisters including: Charles, James, Apolline, Bethia, Marianne, Christine, Jane, Robert, Isabella, Joanna, Andrew, and John Regis Alexander.

Sir William benefited from the intellectual and social advantages of Edinburgh during the Scottish Enlightenment. He was educated with a view to the law and, at an early age, committed himself to a legal career in England.

On 3 May 1771 he was admitted to the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court, and after a prolonged period of study and preparation he was called to the English Bar on 22 November 1782.

He quickly established himself in the Court of Chancery, where he practised for nearly two decades. He developed a reputation as a careful and authoritative lawyer, particularly skilled in matters of equity and real property law which were fields that demanded both technical mastery and sound judgment.

His abilities and professional standing were recognised in 1800 when he was appointed King’s (then Queen’s) Counsel, marking him out as one of the leading advocates of his generation. In 1809 his career advanced further with his appointment as one of the Masters in Chancery, a senior judicial office involving oversight of complex legal and financial matters within the equity courts.

The culmination of Sir William Alexander’s judicial career came on 9 January 1824, when he was appointed Chief Baron of the Exchequer, one of the highest judicial offices in England. Upon assuming this role, he was knighted and sworn in as a member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, reflecting both his eminence within the legal profession and his trusted position within the constitutional framework of the state. As Chief Baron, he presided over cases concerning revenue and finance at a time when Britain was navigating the economic and administrative challenges of the post-Napoleonic era.

After six years in this demanding office, Sir William resigned in December 1830, making way for Lord Lyndhurst to succeed him as Lord Chief Baron. Retirement allowed him to withdraw from public life and return to Scotland, where he lived at his estate in Airdrie, Lanarkshire.

In 1837 he further augmented his landed position by inheriting the estate of Cloverhill in Dunbartonshire, consolidating his status as a Scottish gentleman of means and standing.

Sir William Alexander died in London on 29 June 1842, at the age of eighty-seven. In accordance with his Scottish roots and family connections, he was buried at the small burial ground attached to Roslin (Roslyn) Chapel, south of Edinburgh, a site long associated with notable Scottish families and historical memory. There is a memorial plaque in his name at the Chapel. His estate was worth £140,000 when he died.

Remembered for his integrity, learning, and long service to the law, Sir William Alexander exemplified the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century ideal of the professional jurist: a man whose authority rested not on political ambition but on legal expertise, public trust, and a strong sense of inherited responsibility. His career bridged Scotland and England, Enlightenment-era training and Victorian institutions, leaving a quiet but enduring mark on the British legal system.

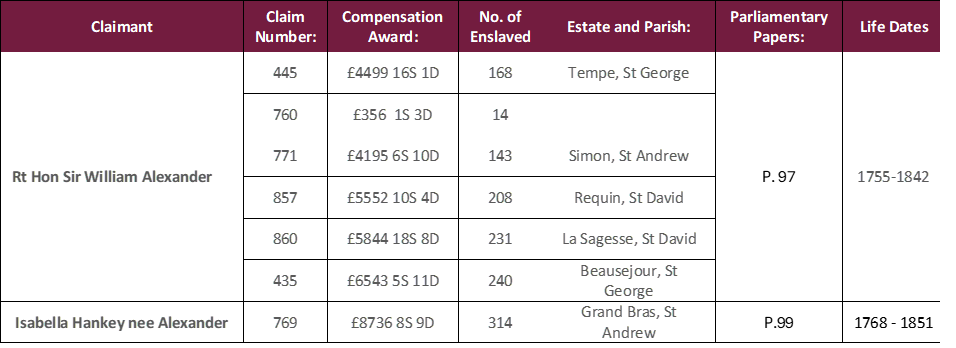

Compensation Claims

Sir William Alexander was among the British elite who benefited materially from the system of slave compensation that followed the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Although he is best known as a senior judge and former Chief Baron of the Exchequer, the compensation records reveal that he was also a substantial absentee claimant with extensive financial interests in enslaved labour on Grenadian plantations. Through a series of awards made in the mid-1830s, Sir William received compensation for enslaved people held on multiple estates across the island, reflecting both the scale and diversity of his colonial investments.

Tempe Estate

Sir William Alexander’s involvement on this estate, claim no. 445, places him firmly within the network of British elites who held substantial financial interests in plantation slavery at the moment of its abolition. The claim, settled on 26 October 1835, related to 168 enslaved men, women, and children and resulted in a total compensation award of £4,499 16s 1d. Although John Alexander Hankey was listed as the first claimant and acted as proprietor and attorney for the estate, Sir William Alexander appeared among the third claimants, alongside members of the Trevelyan family and other prominent figures. This structure indicates that Tempe Estate was held under a complex web of ownership, trusts, and financial obligations rather than by a single individual. Sir William’s position as a third claimant strongly suggests that he held a legally recognised interest in the enslaved people on the estate. The administration of the claim was carried out by Hankey and his attorneys, reflecting the common practice of absentee ownership. Sir William, by this point retired from high judicial office, did not manage Tempe Estate directly and would not have resided in Grenada. Nevertheless, his entitlement to a share of the compensation demonstrates that he benefited materially from the labour of the 168 enslaved individuals whose lives were monetised at emancipation. Their coerced work over many years underpinned the estate’s value and, ultimately, the compensation paid out by the British Treasury. Tempe Estate was one of Sir William Alexander’s most significant Grenadian interests, both in terms of the number of enslaved people involved and the scale of the award. The size of the compensation places the estate among the larger holdings on the island. This claim also highlights the close interconnection between legal authority and slave ownership in Britain. As a former Chief Baron of the Exchequer and Privy Councillor, Sir William stood at the apex of the British legal system, yet he simultaneously held financial interests in enslaved people treated as property under colonial law.

Claim no 760

Sir William Alexander was one of several secondary claimants with a recognised legal or financial interest in a small group of enslaved people. The claim, settled on 16 November 1835, related to 14 enslaved individuals and resulted in a total award of £356 1s 3d. The first claimant was John Alexander Hankey, who was the principal party entitled to compensation and likely held the direct proprietary interest in the enslaved people concerned. Sir William Alexander appears among a larger group listed as third claimants, alongside members of the Trevelyan family, Thomson Hankey, and Sir Robert Heron, some of whom were acting as executors. This configuration strongly suggests that the enslaved people formed part of a complex estate, trust, or mortgage arrangement rather than a single, straightforward plantation ownership. Sir William’s presence as a third claimant is particularly revealing because it shows Sir William operating in his professional capacity as well as his personal one. As a senior lawyer and judge, he was well positioned to act as trustee or executor in complex estates that included enslaved people as assets whose value could be divided among multiple parties with legal claims. His role did not require him to manage enslaved labour directly. Slavery was embedded within British legal and financial structures extending far beyond plantation ownership alone. This smaller claim demonstrates how elite networks bound senior British figures into slavery’s profits, even when their connection to enslaved people was mediated through legal instruments rather than plantation management.

Simon Estate

A much larger award followed under Grenada claim no. 771. Sir William received a share of £4,195 6s 10d for 143 enslaved people. This reinforced his position as a major beneficiary of the compensation scheme and suggests a continuing pattern of investment in plantation slavery. Simon Estate, like many Grenadian plantations, relied on the coerced labour of enslaved men, women, and children whose forced productivity underpinned both colonial wealth and metropolitan careers.

Requin Estate

His compensation portfolio expanded further with Grenada claim no. 857, which yielded £5,552 10s 4d for 208 enslaved people. This was one of Sir William’s largest payments and points to substantial enslaved holdings whose monetary value was transferred directly from the British Treasury to him at emancipation.

Sagesse Estate

Another major award was made under Grenada claim no. 860 for Sagesse Estate, amounting to £5,844 18s 8d for 231 enslaved people. Sagesse was one of Grenada’s better-known plantations, and compensation at this level indicates ownership or control over a very large enslaved population. Taken together with his other claims, this award shows that Sir William’s wealth was significantly bolstered by the final act of state-sanctioned compensation to slaveholders.

Beausejour Estate

Finally, Sir William received a share of £6,543 5s 11d under Grenada claim no. 435 for 240 enslaved people. This was his largest single award and placed him firmly among the most heavily compensated Grenadian claimants.

Note: Sir William was one of a number of claimants for all of these estates. Each estate was awarded a single compensation sum, which was then divided among claimants according to legally defined interests. The order of claimant indicates legal standing (principal claimant, executor, or beneficiary), not equal entitlement.

In the slave compensation records, the first claimant was the principal claimant, usually the collecting proprietor or the person with authority to lodge and receive the award on behalf of the estate.

The second claimant was typically an executor or trustee, recognised because of a formal legal responsibility arising from a will, settlement, or trust.

Third claimants were those with additional legally defined interests in the enslaved people or the estate, such as beneficiaries, co-owners, mortgage holders, or parties named in trust arrangements.

The order in which claimants are listed does not indicate that the compensation was divided equally; it reflects legal standing and the nature of each person’s interest, not the size of the payment they ultimately received.

Viewed collectively, Sir William Alexander’s compensation claims as a 3rd claimant reveal the deep entanglement between Britain’s legal, political, and judicial elite and the economics of slavery. While he occupied one of the highest judicial offices in the land and sat on the Privy Council, he was simultaneously a beneficiary of a system that treated enslaved people as financial assets. His compensation awards illustrate how abolition reinforced elite wealth derived from slavery converting human lives into state-backed monetary payments that flowed directly into the hands of men like Sir William Alexander.

Sir William Alexander and the Slave Registers

Sir William does not appear as a named owner in the Grenada slave registers, despite being a major beneficiary of enslaved labour on the island. This absence reflects the way slave ownership was structured rather than a lack of involvement. As a senior British judge, Privy Councillor, and absentee investor, Sir William’s interests in Grenadian estates were held through trusts, mortgages, executorships, and shared ownership arrangements. Day-to-day control of enslaved people was exercised by local proprietors, attorneys, or estate managers, whose names were recorded in the registers instead.

The slave registers were designed to track the movement, numbers, and legal status of enslaved people, not to expose the full chain of financial or beneficial ownership. As a result, figures such as Sir William remain largely invisible in these records.

His presence emerges only when the system ended, in the compensation claims, where his legal entitlement to enslaved people was formally acknowledged and converted into cash. His absence from the registers therefore highlights a structural feature of British slavery: elite beneficiaries were often shielded from direct identification with the enslaved people who sustained their wealth.

Isabella Hankey nee Alexander

Isabella HANKEY was Sir William’s sister. She married the London West India merchant John Peter HANKEY (1770-1807) and was the mother of John Alexander HANKEY. She passed away in 1851, leaving a personal estate valued at £120,000. Although not listed in the compensation awards, she inherited estates and enslaved people in Grenada, actively managing her inheritance as an absentee owner.

Her will, proved on January 31, 1851, detailed her bequests. She left the manor of Essendine in Rutland to her eldest son, John Alexander HANKEY, and stipulated that her son Henry Aitchison HANKEY would not benefit unless he renounced an annuity she had charged on her real estate.

Her husband had left his Grenada estates, including sugar works and enslaved people, in trust. Two-thirds of these estates were for Isabella’s lifetime, with one-third to be disposed of by her.

Isabella also purchased additional property in Grenada, which she left in trust to her sons John Alexander HANKEY and Thomson HANKEY junior, to be divided among her four children: Julia Bathurst, John Alexander, Henry Aitchison, and William. Julia received portraits and other effects, while each son was initially bequeathed £20,000.

A codicil in 1848 revoked some bequests, dividing her estate three ways among her sons and leaving the Grosvenor Square house to Julia.

Another codicil in 1850 addressed potential compulsory purchases by the Great Northern Railway, directing proceeds to John Alexander Hankey.

John Peter HANKEY’S will, proved in 1807, specified that his estates in Grenada would be divided among his children after Isabella’s death. Isabella’s daughter, Julia, died in 1877, also leaving £120,000.

Grand Bras Estate, St Andrew

Isabella played a significant and long-lasting role in the ownership and control of Grand Bras Estate

After the death of her husband, John Peter Hankey, in 1807, Isabella’s relationship to Grand Bras shifted from that of a spouse within a mercantile-plantation family to an active property holder in her own right.

Her will records that she purchased a one-eighth share in Grand Bras Estate from Sir Morris Ximenes, thereby consolidating her proprietary interest. This purchase is important as it demonstrates deliberate investment and agency in a Grenadian slave estate.

From 1807 until 1851, Isabella held Grand Bras as a tenant-for-life, meaning she was entitled to the income and benefits of the estate for the duration of her life, even though the underlying capital interest may ultimately have passed to heirs or trustees. During this period, she was recognised as a joint owner, sharing legal and financial interests with other members of the Hankey family, notably Thomson Hankey, who is recorded as a joint owner from 1817 to 1832.

Isabella’s ownership sat within a much older and complex structure of shared proprietorship. Grand Bras had long been divided into fractional interests held by elite British figures, including Sir Thomas Charles Bunbury, Lauchlin Macleane, and Clotworthy Upton, many of whom had earlier delegated management to London merchants such as Simond & Hankey.

The estate was also heavily financialised. In 1775 it was mortgaged, along with the enslaved people attached to it, to David Garrick. This illustrates how enslaved labourers were treated as collateral within metropolitan credit networks that Isabella later inherited into.

Although she did not reside in Grenada, her interests were exercised through attorneys and agents, including Bridgeman Hewitson and John Stokes, who managed the estate, its enslaved workforce, and its commercial operations on behalf of the owners.

Finally, we can state that Isabella Hankey’s involvement in Grand Bras Estate was active, sustained, and financially consequential. She expanded her stake through purchase, held legal rights to the estate’s income for over four decades, and participated, through agents, in the plantation economy that depended on enslaved labour. Her role illustrates how elite British women could be embedded participants in Caribbean slavery, exercising ownership and control through legal instruments even while remaining geographically distant from the plantation itself.

Isabella Hankey and the Slave Registers

Despite being a joint owner and tenant-for-life of Grand Bras Estate from 1807 to 1851, Isabella does not appear by name in the Grenada slave registers. Her interests were represented through attorneys, agents, or co-owners who acted on her behalf in Grenada. Enslaved people on Grand Bras were therefore registered under the estate name or under the names of local managers rather than under Isabella’s own.

This absence should not be mistaken for a lack of ownership or agency. Isabella’s will records her purchase of a one-eighth share in Grand Bras following her husband’s death, demonstrating an active decision to invest in and consolidate her stake in the estate. For more than four decades, she was legally entitled to the income generated by enslaved labour there. The registers obscure this reality because they privileged operational control over beneficial ownership and because women’s property rights were commonly mediated through legal instruments rather than personal registration.

Isabella Hankey’s case shows how enslaved people could be owned by women whose names were largely absent from colonial administrative records, even while their financial rights were firmly protected. Her involvement at Grand Bras illustrates how slavery was sustained by absentee families, widows, and investors whose authority operated through law, inheritance, and credit rather than physical presence.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

William Alexander (judge) - Wikipedia

Rt. Hon. Sir William Alexander - www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/45714

Isabella Hankey (nee Alexander) https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146634544

Grand Bras Estate https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/1303