The Aerstins

Fact File: Elizabeth Aerstin

Claim Number: 147

Compensation Award: £27 10S 5D

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1

Parish: St. George Parliamentary Papers: p. 95

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

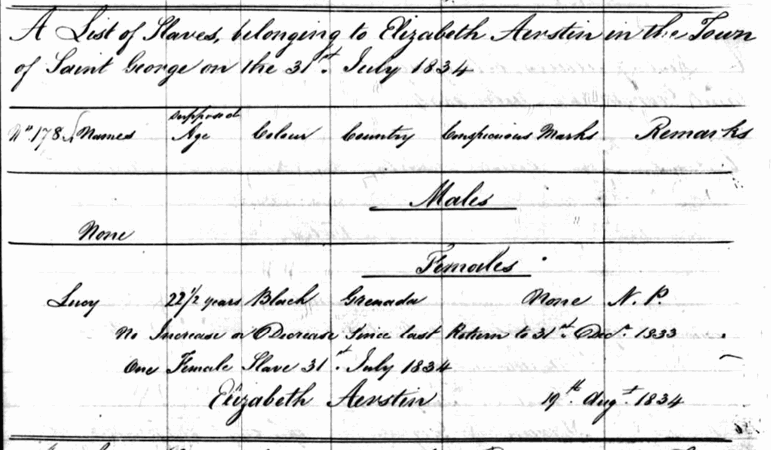

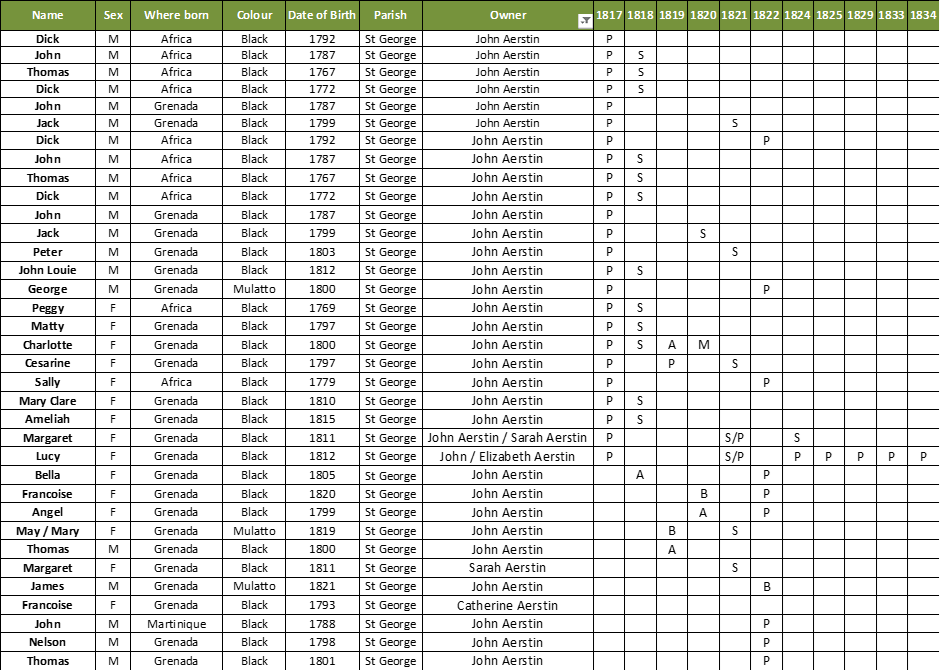

The Aerstin family, as recorded in the early 19th-century Slave Registers of Grenada, appears to be part of a small, interconnected group who were involved in the enslavement of people. The family is likely connected through blood relations, with John, Elizabeth, Sarah William and Catherine Aerstin all listed as proprietors in the Slave Registers. Their holdings were relatively modest compared to larger plantations.

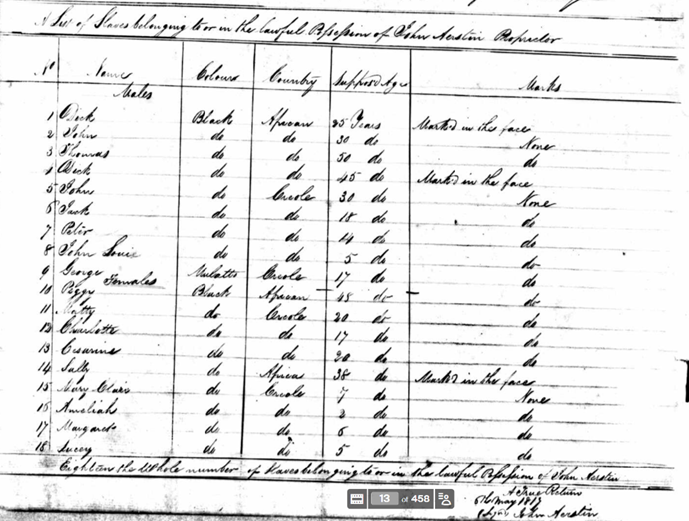

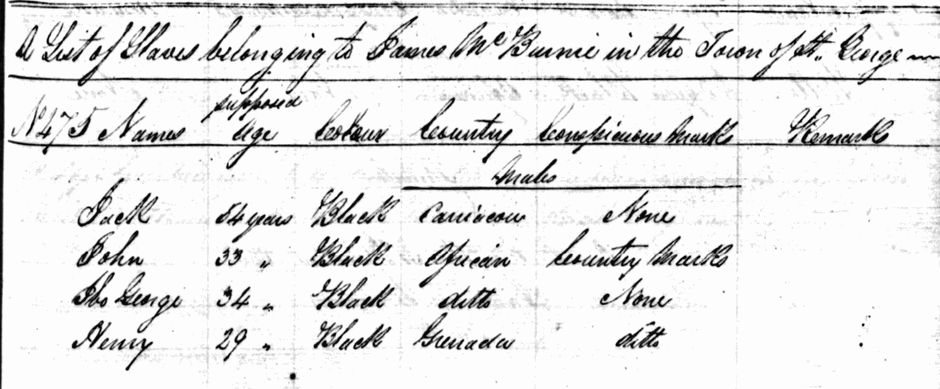

John Aerstin emerges as the central figure in the family’s history in early-19th-century Grenada. In 1817 he was based in St George that held eighteen enslaved people.

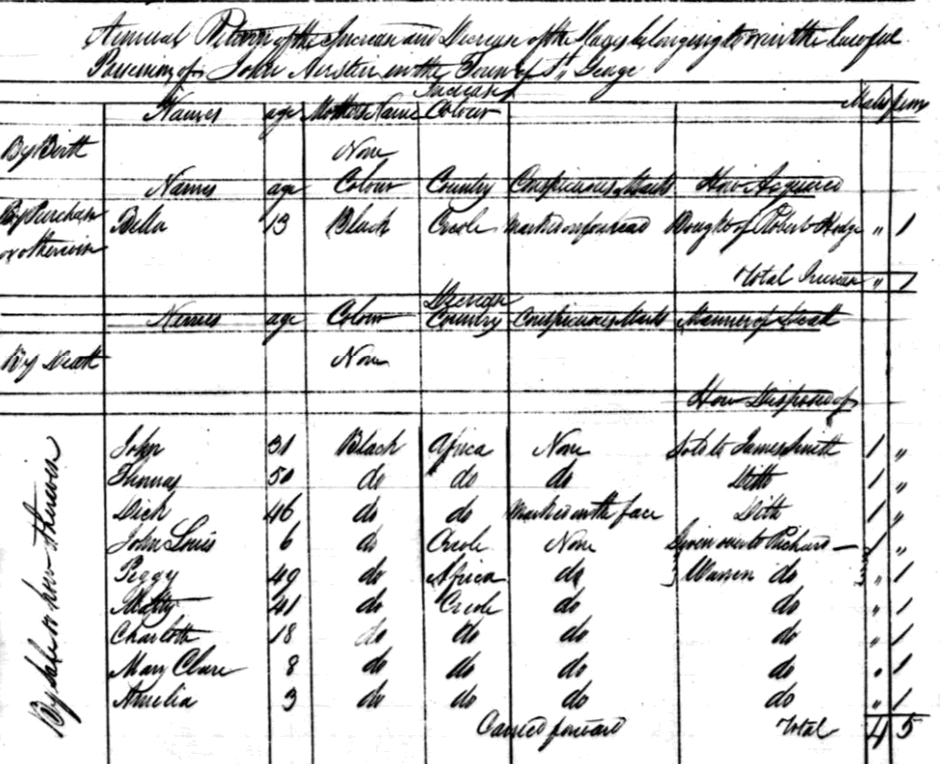

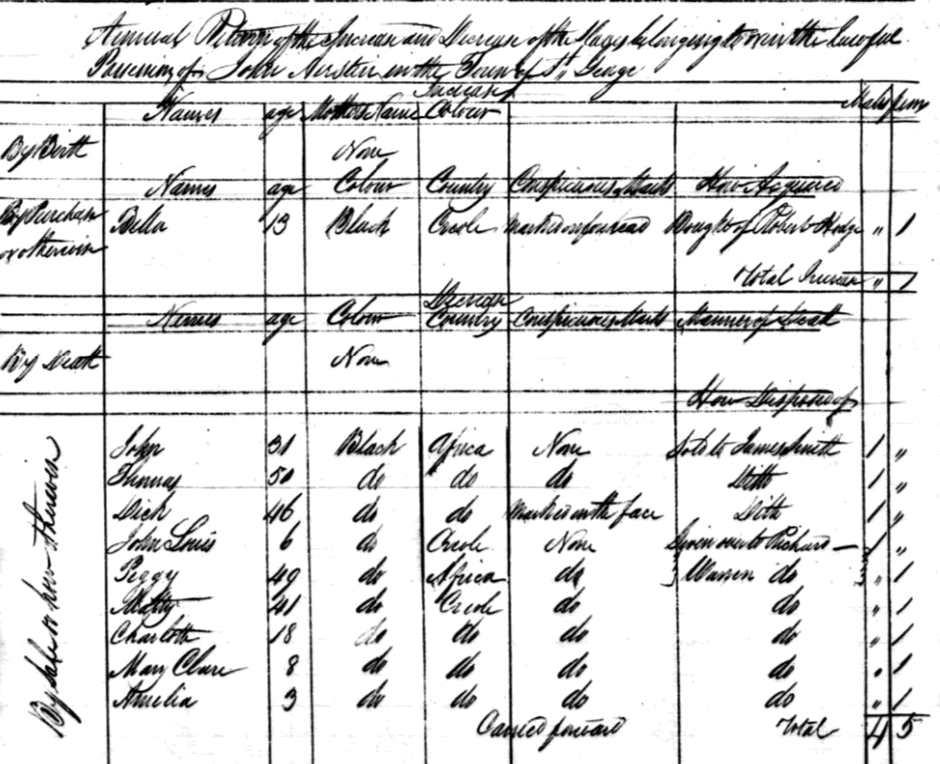

The 1818 register showed a number of changes. John bought 13 year old Grenadian Bella from Robert Hodge. He sold John, Thomas and Dick to James Smith. John Louis, Peggy, Matty, Charlotte, Mary Clare and Amelia were also sold, this time to Richard James Warren.

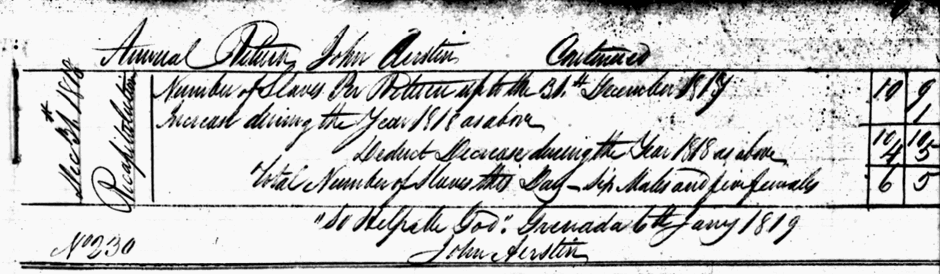

He ended the year with 11 enslaved people under his control.

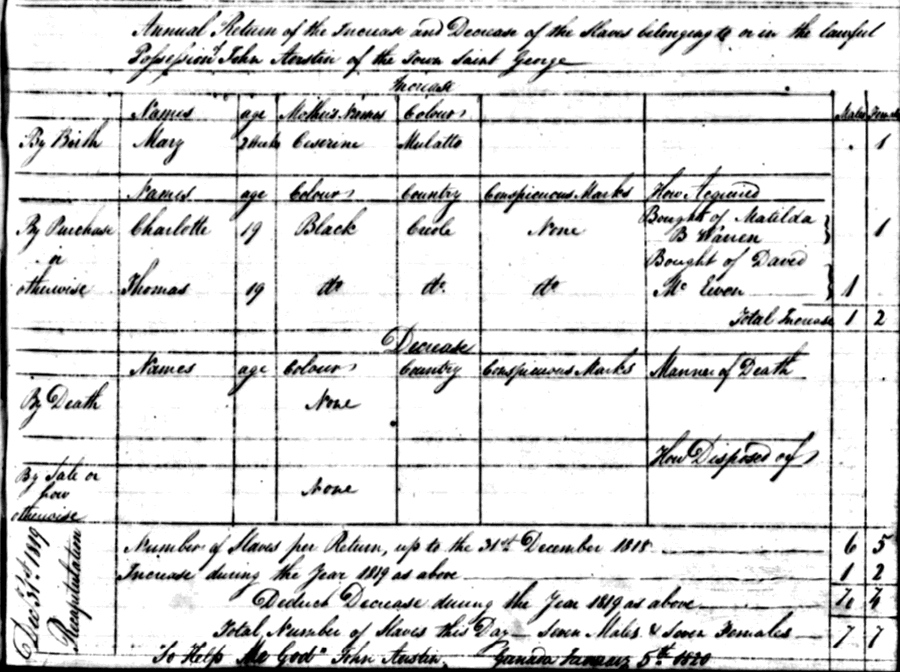

In 1819, the Slave Register shows that a child named May was also born under his control. Her mother, Cesarine, was described as a Black Creole, born in Grenada, while May was listed as a mulatto child, her mixed parentage left unspoken but implicitly revealing the dynamics of power on the plantation.

John enslaved two more people that year; Charlotte from Matilda B. Warren (perhaps the same Charlotte that was sold the year before) and Thomas from David McEwen. They were both 19 years old.

John enslaved two more people that year; Charlotte from Matilda B. Warren (perhaps the same Charlotte that was sold the year before) and Thomas from David McEwen. They were both 19 years old.

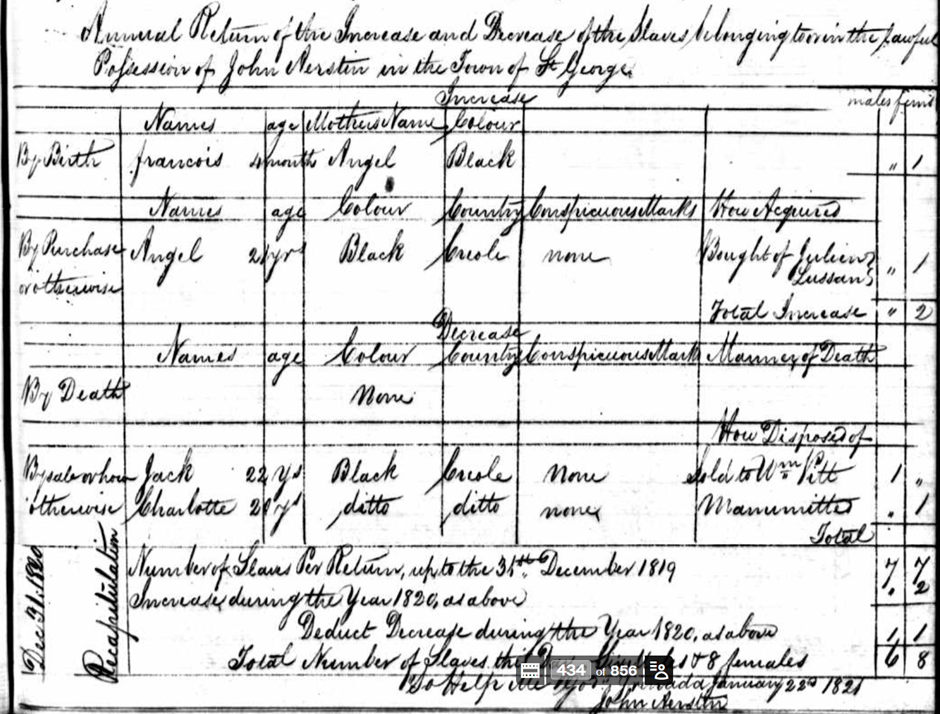

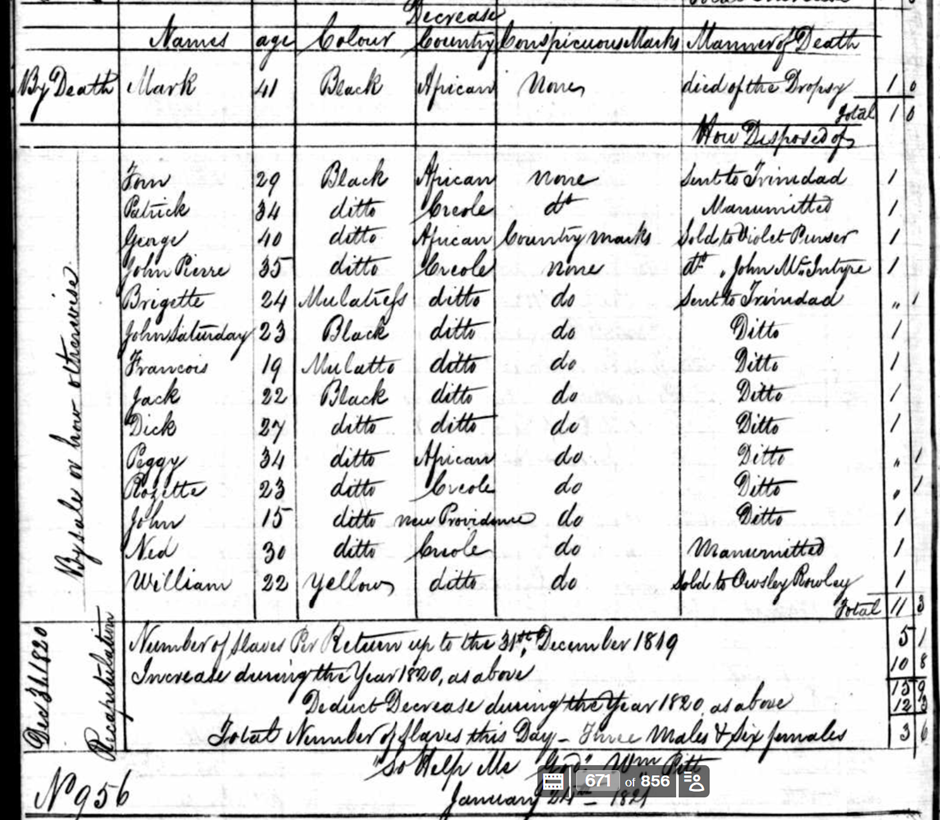

In the 1820 Slave Register, John had 14 enslaved people under his control (6 male, 8 female). He made the following changes. He sold Jack (22) to William Pitt and manumitted Charlotte (20). He bought Angel (21) who gave birth to a daughter Francoise.

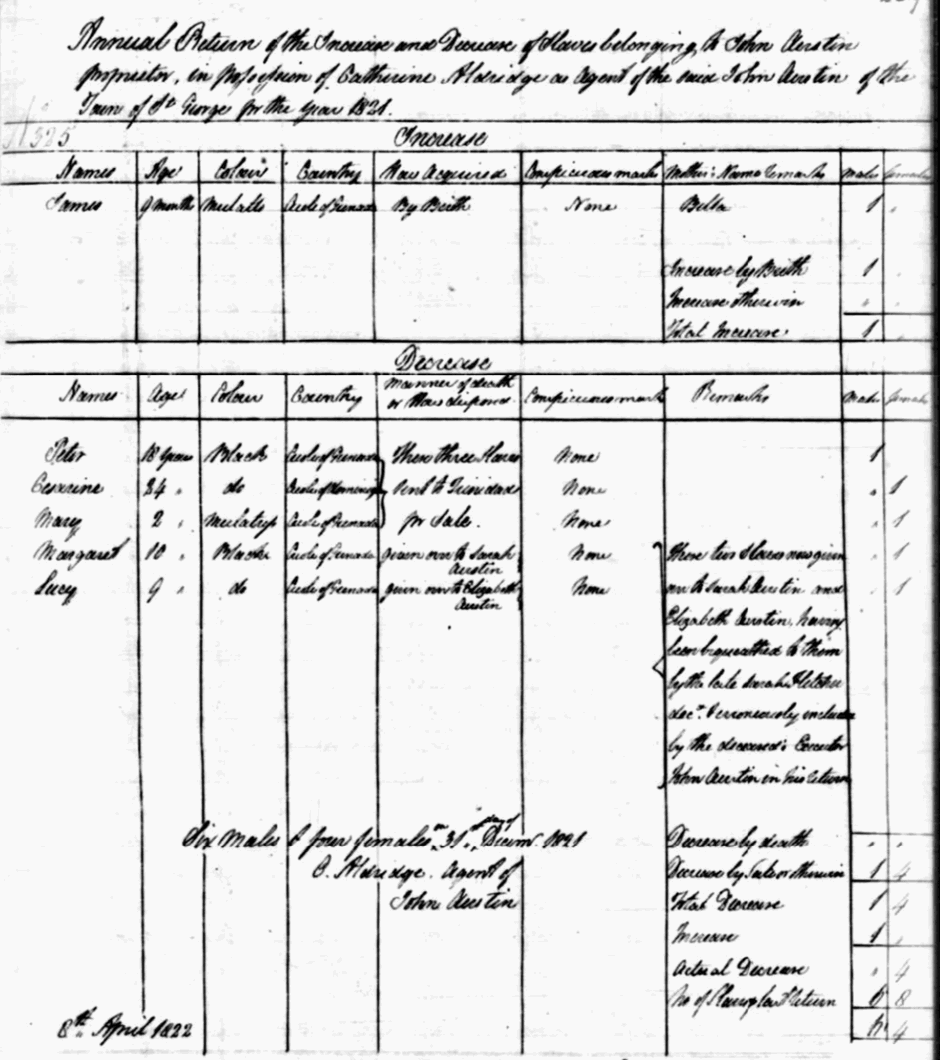

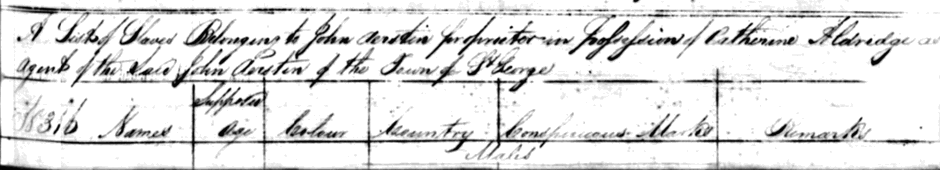

The 1821 Slave Register shows that he had placed his interests under the possession of Catherine Aldridge.

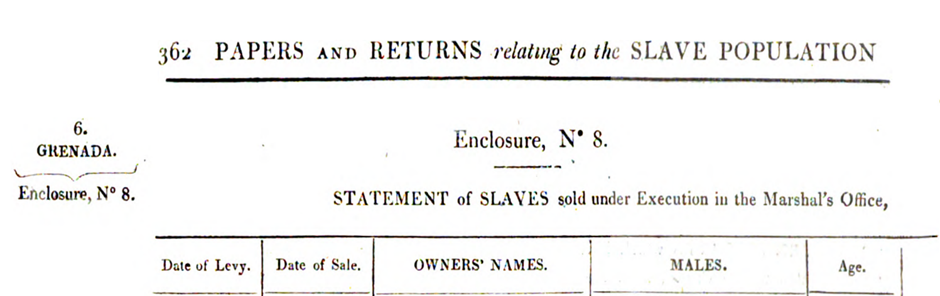

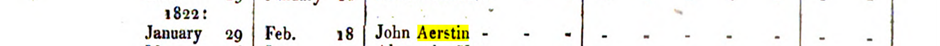

Peter, Cesarine, and May were shipped to Trinidad for sale, while Margaret and Lucy were transferred to Sarah and Elizabeth Aerstin respectively under a contractual arrangement tied to the late Sarah Fletcher, John was the executor of her will. It is likely that he was closely related to Sarah and Elizabeth in some way. There is a record of John AERSTIN selling an enslaved worker under execution in the Marshall’s office on 18 Feb 1822.

Peter, Cesarine, and May were shipped to Trinidad for sale, while Margaret and Lucy were transferred to Sarah and Elizabeth Aerstin respectively under a contractual arrangement tied to the late Sarah Fletcher, John was the executor of her will. It is likely that he was closely related to Sarah and Elizabeth in some way. There is a record of John AERSTIN selling an enslaved worker under execution in the Marshall’s office on 18 Feb 1822.

The Slave Register of this year, again under the possession of Catherine Aldridge showed 6 males and 4 females under his control. James was 9 months old.

The Slave Register of this year, again under the possession of Catherine Aldridge showed 6 males and 4 females under his control. James was 9 months old.

He likely died before emancipation, which would explain why no compensation claim exists under his name. There is also a record of a John Aerstin who died in Grenada in 1831, aged 29.

He likely died before emancipation, which would explain why no compensation claim exists under his name. There is also a record of a John Aerstin who died in Grenada in 1831, aged 29.

John may have had children with a woman recorded variously as Elizabeth Bagenhall, Backenhall, or Ballingale. The records of Samuel (1808) Ann (1807), Jane (1810), and Charles Aerstin (1814) suggest that a parallel domestic life existed alongside his role as plantation owner. There is also a record for the birth of Thomas Aerstin with Louisa Harris in 1820, Elizabeth Helen Aerstin with Catherine Pire in 1829.

Elizabeth Aerstin

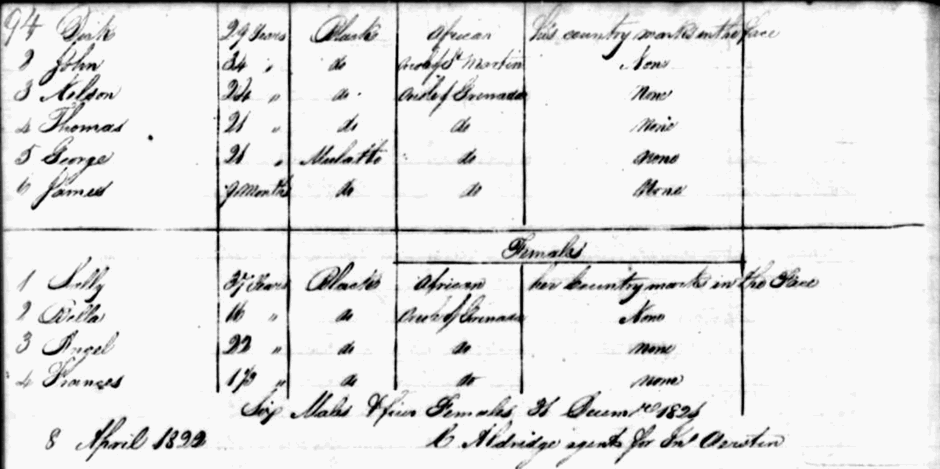

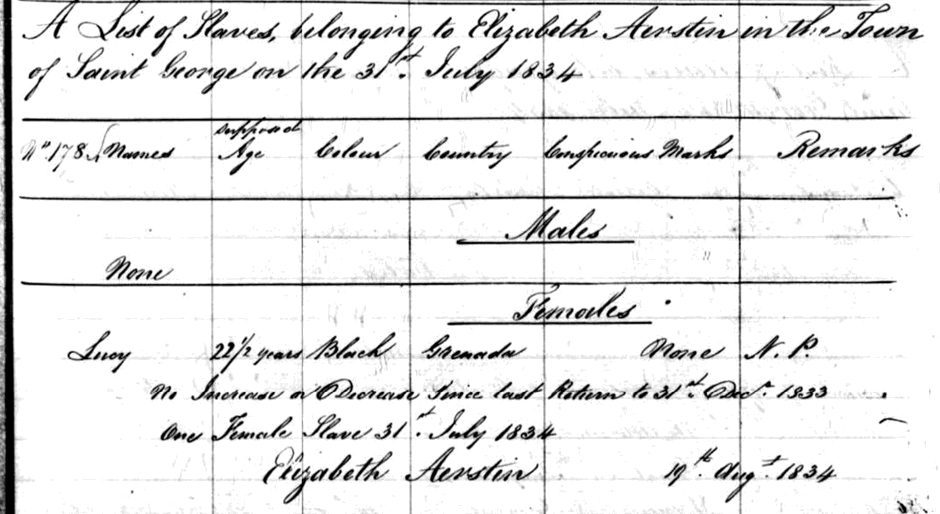

Elizabeth comes into focus through the 1821 Slave Register, when she appears as the owner of Lucy, who had been bequeathed to her by the late Sarah Fletcher. The record reads “This Slave bequeathed to me Sarah Aerstin by the late Sarah Fletcher deceased & commonly included by the deceased’s Executor John Aerstin in his return”

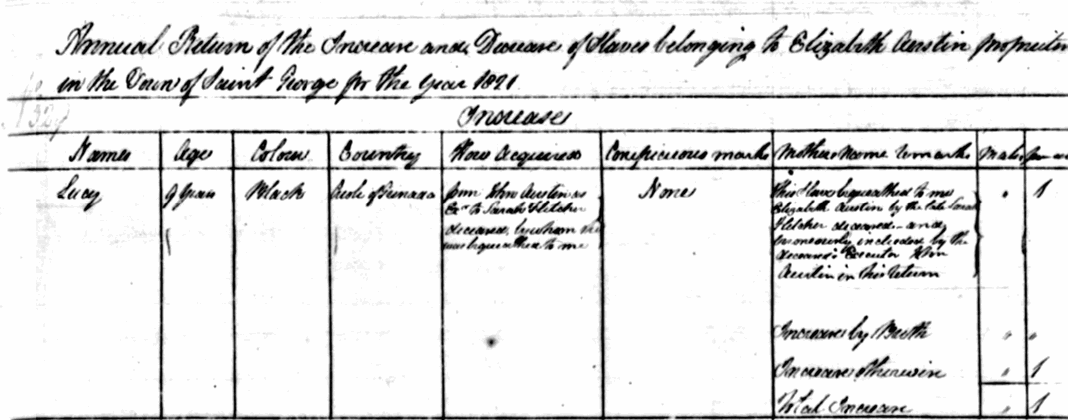

This transfer was formalised through the executor, John Aerstin. For more than a decade, Elizabeth’s register entries show no change: she owned only Lucy, and her holdings neither grew nor diversified. Elizabeth’s life appears modest compared with John’s. She had enslaved one person and did not engage in buying or selling others. Lucy appeared in the registers of 1824, 1825, 1829, 1833 and 1834.

When emancipation came in 1834, her enslaved worker, Lucy, by then 22½ years old, was legally freed. Elizabeth later received compensation in October 1835, amounting to £27 10s 5d, for the loss of Lucy’s labour.

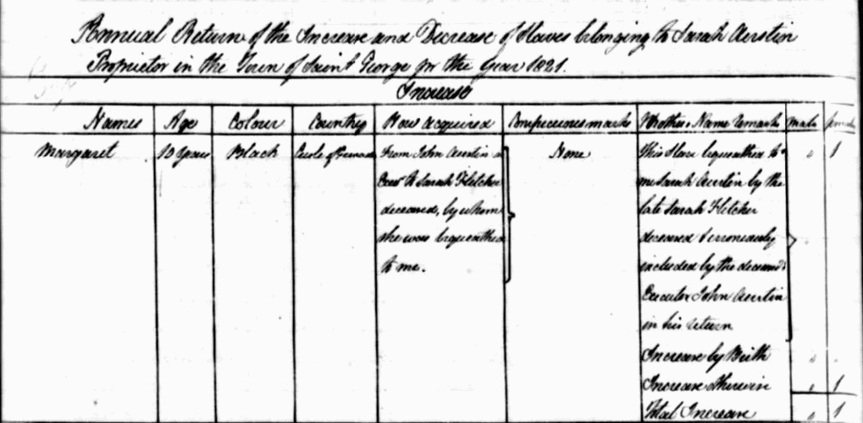

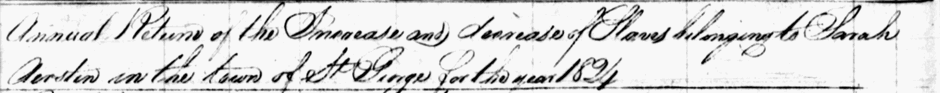

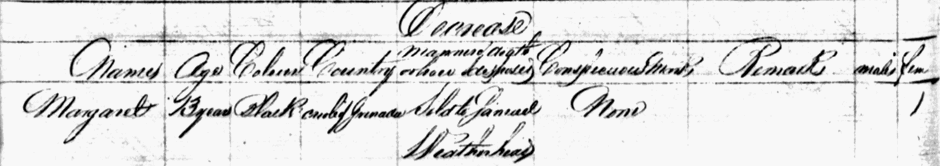

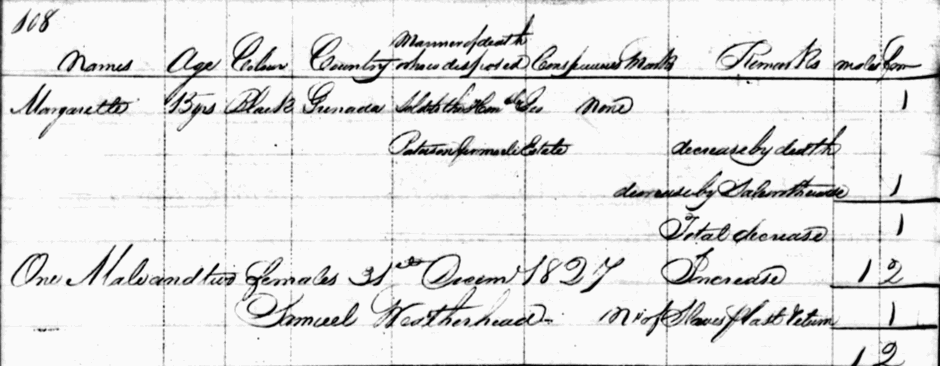

Sarah AERSTIN was also included in the 1821 register. She is listed as the owner of Margaret, a ten-year-old bequeathed to her by the late Sarah Fletcher under the same executor, John Aerstin, like Elizabeth. Sarah’s small-scale ownership resembles Elizabeth’s.

Sarah AERSTIN was also included in the 1821 register. She is listed as the owner of Margaret, a ten-year-old bequeathed to her by the late Sarah Fletcher under the same executor, John Aerstin, like Elizabeth. Sarah’s small-scale ownership resembles Elizabeth’s.

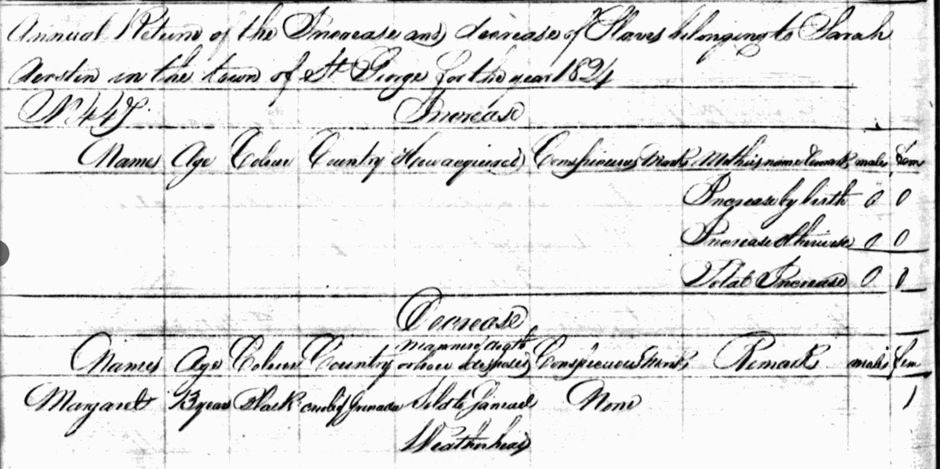

By 1824 she had sold Margaret, then aged thirteen, to Samuel Weatherhead. She held one other female enslaved person at that time, though no further details are recorded. After 1824, Sarah disappears from the registers entirely. Whether she died, migrated, married under a different surname, or simply ceased to own enslaved people remains unknown.

William Aerstin

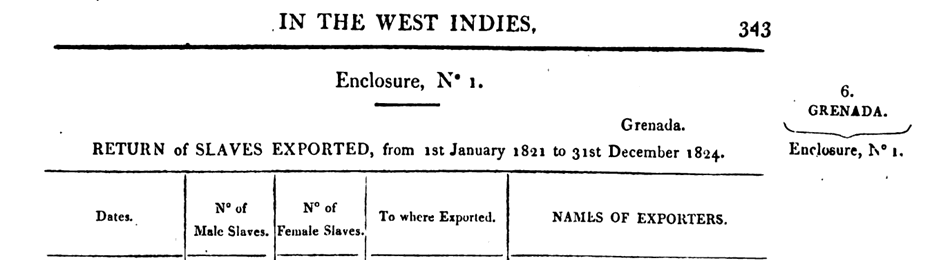

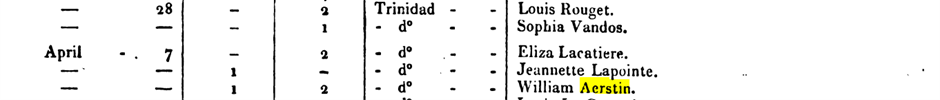

William Aerstin appears briefly but significantly. On 7 April 1821 he exported three enslaved people; two females and one male, from Grenada to Trinidad. These individuals may have been the same Peter, Cesarine, and her daughter May who had been enslaved by John Aerstin and were removed around the same period. His actions suggest that William participated directly in the inter-Caribbean slave trade.

There is a record of a William and Rose Aerstin having a son, Edmund, born on 9 November 1823 in St George.

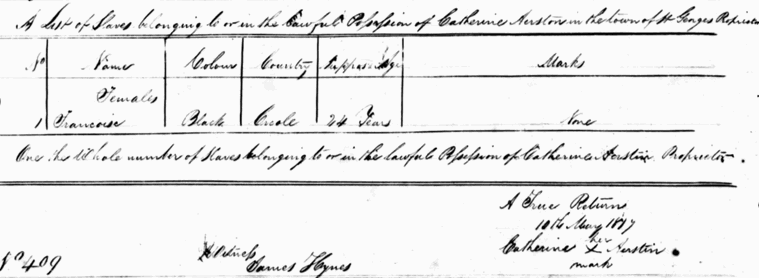

Catherine Aerstin

Catherine enters the historical record in 1817 as the enslaver of a woman named Francoise in St George. Her involvement appears minimal, and it is unclear how she connects to John or the others. She may have been a relative, wife, or widow, or simply part of a wider Aerstin network in the parish.

Summary

Collectively, the Aerstins formed a small but active slave-owning family in St George, participating in the transfer, management, and sale of enslaved people between at least 1817 and 1834. Their activities spanned ownership (John), small-scale inheritance and custodianship (Elizabeth and Sarah), and intercolonial exporting (William). The Aerstin family’s slaveholding activities were relatively small in scale but typical of the era, involving the inheritance and sale of enslaved people within family structures. The connection between John, Elizabeth, and Sarah suggests a tight-knit family unit. The lack of further records for Sarah and the relatively limited number of enslaved people held by Elizabeth contrasts with the slightly larger operations overseen by John before his death. The family appears to have profited from the British system of compensation after abolition, which rewarded slaveholders for the loss of "property" when enslaved individuals were freed.

The Enslaved

The people enslaved by the Aerstins reflect the human stories behind the numbers, registers, and transactions. They include children, mothers, young adults purchased for labour, and individuals forcibly exported across the Caribbean.

John, Thomas and Dick

Born in Africa, John, Thomas and Dick had all crossed the Atlantic in chains and survived the horrors of the Middle Passage. All carried with them memories of another continent, a childhood spent beneath a different sun, before being forced into a world that stripped them of their name and history. All three were bound by a shared experience of loss and endurance.

In 1817, their names appeared together in the records of the John Aerstin their lives catalogued as property. Then, in 1818, their fates intertwined yet again as they were sold together to James Smith. The sale meant the wrenching separation from what little community they had built, but it also meant that, at least for now, they would not face the unknown alone.

You can imagine, on the journey to their new destination, they would reminisce of the stories from their homeland, whispering fragments of songs and traditions that had survived the years. Thomas, despite his fifty years remained a figure of quiet strength, his endurance a silent testament to resistance. John, the youngest at 30, drew strength from their presence, learning that survival was not just about the body, but about memory and companionship.

They faced an uncertain future. Yet, by holding onto each other, they carried with them the spirit of endurance and the hope that, no matter how the world sought to break them, their lives and their memories of Africa would persist.

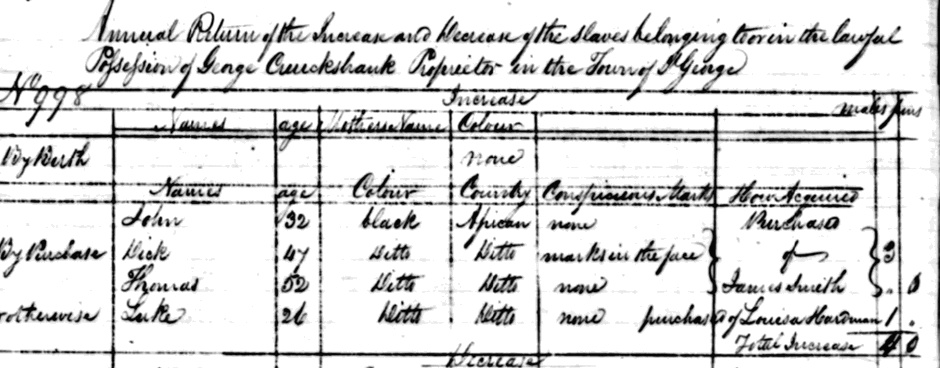

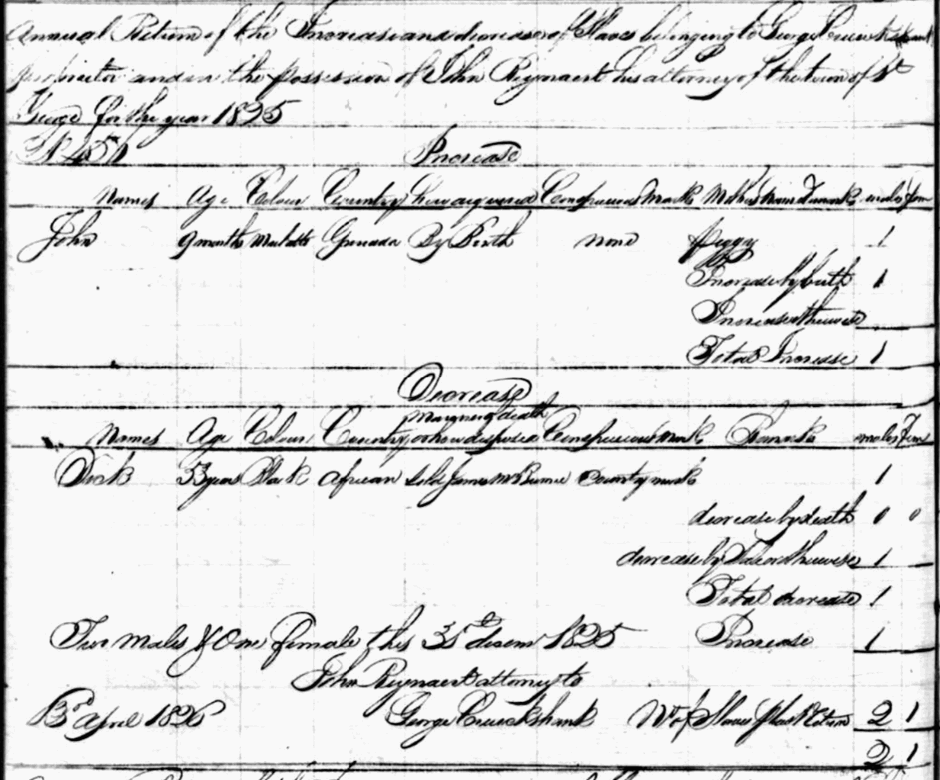

But their reprieve was brief. James Smith, into whose hands they had been delivered, did not intend to keep them for long. Almost immediately, he arranged their sale to George Cruikshank, another figure in the tangled web of Caribbean slavery. For John, Dick, and Thomas, it was another abrupt transition, their fates dictated by the shifting interests of men whose lives were built on the trafficking of others.

This was the last we saw of Thomas.

This was the last we saw of Thomas.

James Smith appears from the record to be more of a middleman than a long-term owner. His rapid transfer of the men suggests he was a trader, one who moved enslaved people as commodities, seeking profit in every transaction rather than seeking to cultivate or manage estates. For John, Dick, and Thomas, this meant their lives were measured in values and exchanges rather than roots or relationships, and each new sale threatened further separation and uncertainty. Still, moving as a group, they clung to the fragments of familiarity and memory that could not be sold, even as the world around them changed with every transaction.

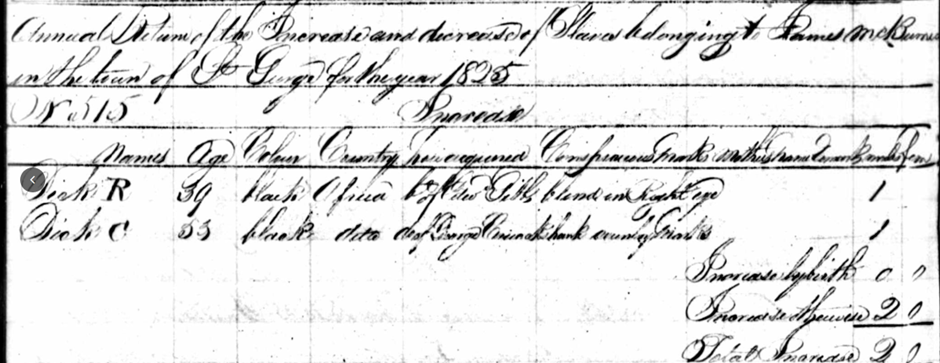

Dick was sold again on 1825 to James McBurnie. The record now whos him to have country marks most likely on his face. This transaction marked yet another upheaval in Dick’s life, as he was forced to leave behind any sense of stability he might have begun to rebuild. Each sale chipped away at the fragile connections to people and place, but Dick’s repeated presence in the records is a testament to his endurance. Despite the unrelenting cycle of displacement and uncertainty, he continued to survive his story a silent chronicle of resilience amid continual upheaval.

George Cruikshank went on to claim compensation for 3 enslaved people. There was a black African called John who was one of them but born c.1791. As birth dates of enslaved Africans were not recorded by traders, their age was assumed and manipulated for commercial gain. Could this in fact be the John we are following. If so, he managed to survive through this entire ordeal!

Dick appears in James McBurnie’s 1825 register, age 59. Now known as Dick C as there was another Dick in the register. There was an African John listed too but the dates don’t match the one we are following and the country marks would be a change from the earlier records – but we saw this change with Dick. This was the last we saw of Dick.

Jack, Dick and Peggy

Jack (21), Dick (28) and Peggy (51) were sold to William Pitt in 1820. They faced another sudden displacement. This was further impacted by their onward sale as William sent them to Trinidad with a few others.

Their fortitude lies in the courage with which they confronted the unknown: torn from familiar surroundings, yet carrying with them unspoken resilience that they needed to survive.

Peter

Peter was born enslaved in Grenada and was transported to Trinidad just as he entered adulthood in 1821. His fortitude is found in his journey: the heartbreak of removal, the strength to adapt again, and the courage to continue living in a world that repeatedly uprooted him.

John Louis, Peggy, Matty, Charlotte, Mary Clare and Amelia

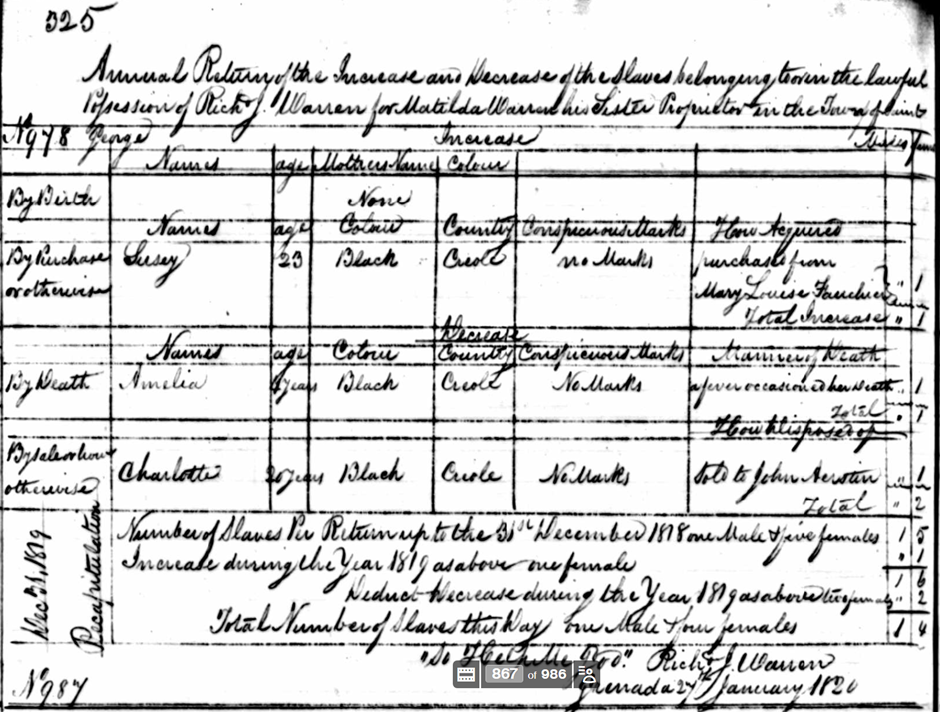

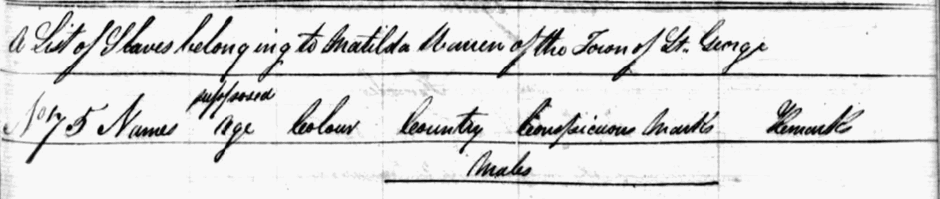

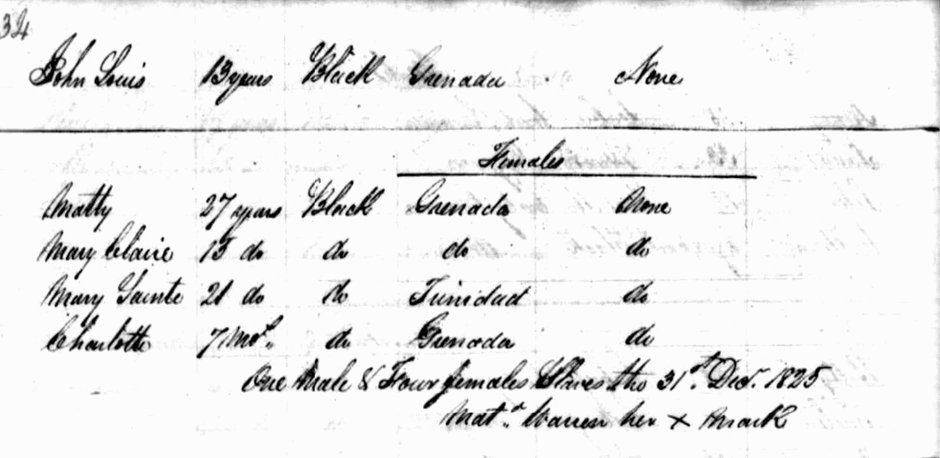

We can see from John Aerstin’s register that these were all sold to Richard James Warren in 1818.

Richard Warren’s slave register for 1819 tells us more. Richard was the legal owner but they were for his sister Matilda Warren who was a business owner in St George. He recorded Amelia’s death that year, age 47 from a fever. He also sold Charlotte (20) to John Aerstin.

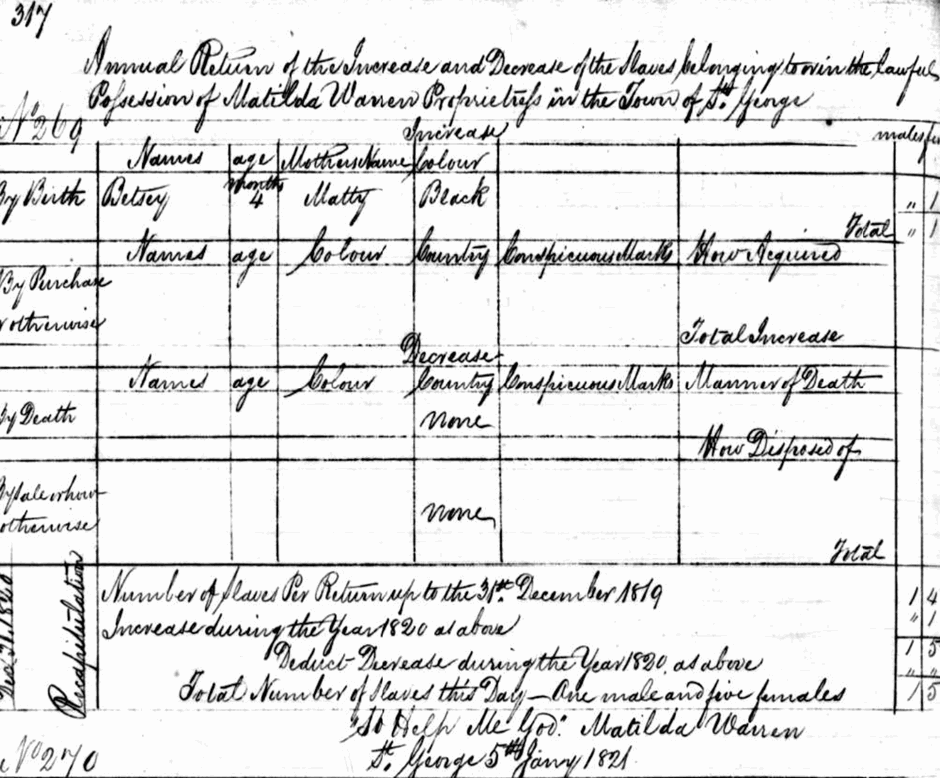

The following year, we see that Matty gave birth to a daughter Betsey and that the holding was in the lawful possession of Matilda and not Richard. In fact, it might be safe to assume that he had died as his name disappears from all future records.

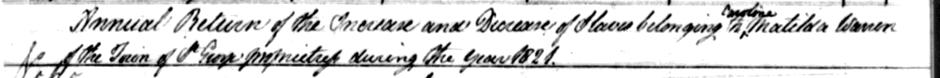

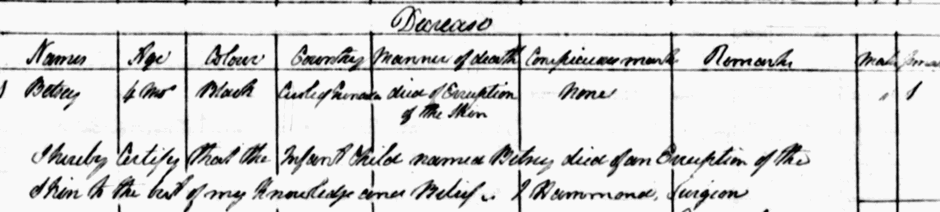

Unfortunately, Betsey died in infancy aged 4 months. The record says that she died from eruption of the skin which was a term used to describe a range of issues including ulceration, yaws (a common chronic infectious disease) or even smallpox. As enslaved people had limited access to medical treatment, a mild skin eruption could become life-threatening through infection, fever or septicaemia.

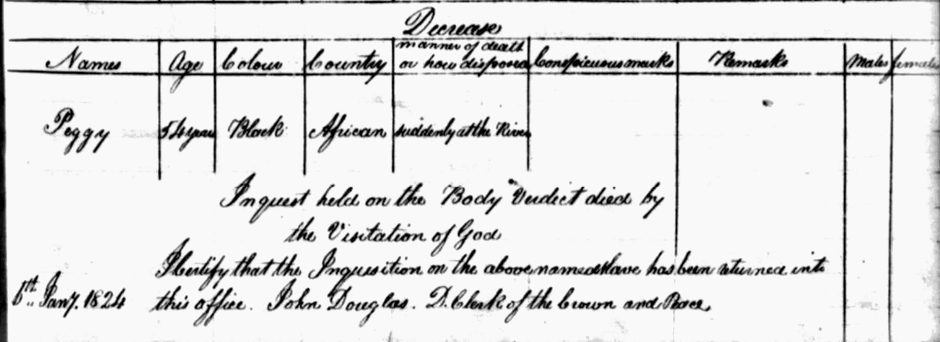

Sadly, Peggy died in 1823. An inquest concluded that she had died by the virtuation of God which really meant she passed by natural causes, at 54 years old. The inquest may have been called for because of the suddenness of her passing. The Amelioration Act that was passed in 1823 required such an inquest if a death had been sudden, suspicious or resulting from severe punishment. The act was passed as the British government were facing huge pressures from abolitionists and wanted the system to appear more humane and reassure Parliament that the system was being reformed. A coroner would be appointed and a white jury. Even if the death had been as a result of brutal treatment, the enslaved witnesses were not allowed to testify and prosecutions of the perpetrators were almost non-existent.

We see John Louis (13), Mary Claire(15) and Matty (27) and in Matilda’s register of 1825.

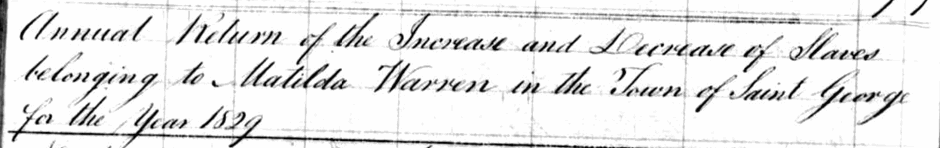

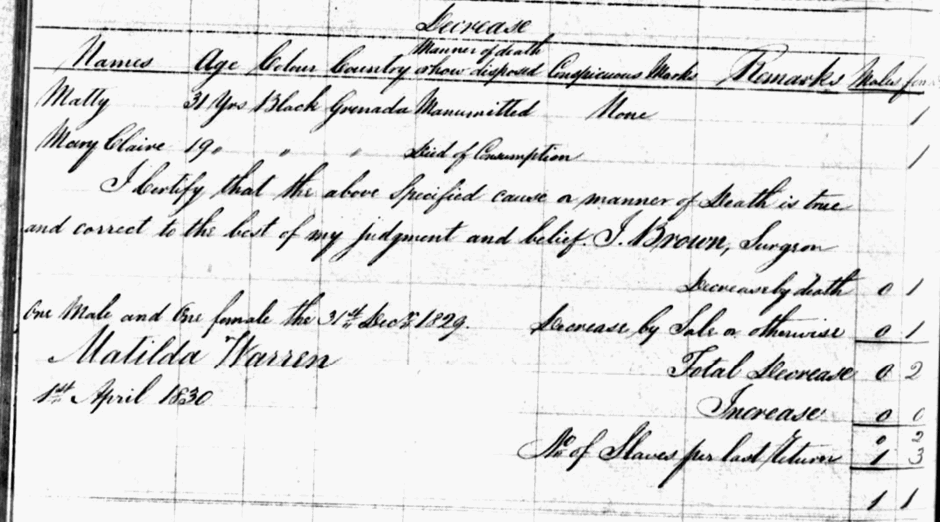

There was mixed news in 1829.

Matty was manumitted in that year and was free from bondage that had been part of her whole life to that point. At 31, she could finally start planning the rest of her life.

Mary Claire died of consumption. This was a common condition in enslaved people due to the unsanitary and confined conditions they had to live in. She was just 19.

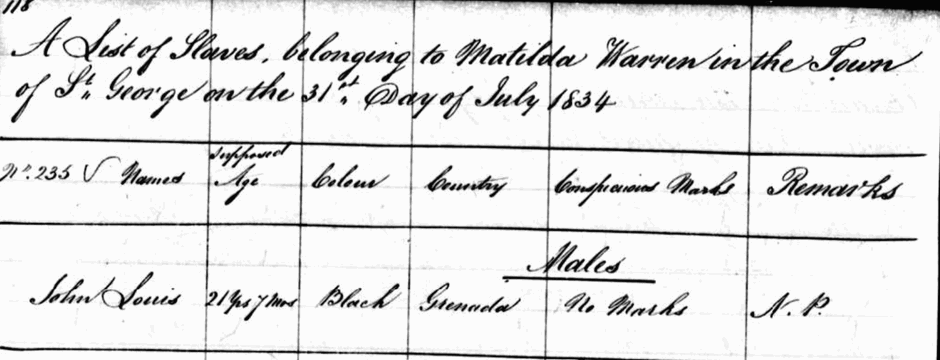

Matilda went on to claim compensation for the 5 people she had enslaved in 1834. One of which was John Louis. He survived! He was also just 21 years old so, after the period of apprenticeship, he would have been free to live a life more of his choosing.

Cesarine and May

Cesarine was a black woman born in Grenada. She gave birth to May in 1819 from a white father (likely to have been an overseer). She was transported to Trinidad, thankfully with May, for onward sale in 1821. Despite all this, she remained a mother, a survivor, and an important constant for her daughter.

Margaret

Margaret saw many changes in her early life. She first appears in the register of 1817 under the control of John Aerstin. She was then transferred to Sarah Aerstin in 1821 who sold her to Samuel Weatherhead in 1825.

She was on the move again in 1827 as Samuel sold her on. She was still just 15 years old.

Margaret’s childhood consisted of constant reassignments between households. Each shift required adaptive strength. Her ability to withstand separation, reattachment and new environments is itself remarkable.

Lucy

Lucy possesses one of the longest and clearest life histories in the Aerstin records. She was transferred to Elizabeth Aerstin in 1821 and remained with her through 1834. Her survival from infancy to adulthood during the harshest years of slavery demonstrates deep resilience. In 1834 she finally saw the end of enslavement at 22, living proof that fortitude endures even when freedom is delayed.

Angel and Francoise

Angel was taken under John Aerstin’s control in 1820 and gave birth to a daughter, Francoise soon afterwards. She was 21. Angel would have to negotiate a life of demands, long hours on top of motherhood. Yet she continued, nurturing her daughter despite uncertainty about their future. Francoise represents the fragile but determined emergence of new life in an environment built on oppression.

John

This Martinique-born man, present in 1829, had already endured migration between islands. His appearance suggests a life shaped by multiple colonial systems. His fortitude lies in surviving across borders, labour regimes, and decades of upheaval.

Summary

The stories of the enslaved associated with the Aerstin family reveal lives marked by relentless upheaval, resilience, and adaptability. Though many of their names appear briefly in the records, their legacies were anything but small. They became the ancestors of many Grenadians living today, the builders of villages and farming communities, the first to negotiate wages, purchase land, educate their children, and establish the foundations of the island’s modern society. Their transition from bondage to freedom was a generational rebirth. In this way, the stories of the enslaved connected to the Aerstins do not end in tragedy but in continuity. Their endurance ensured that Grenada’s cultural, familial and historical lines survived, and their descendants inherited not only freedom but a strength rooted in centuries of perseverance. Their lives, though obscured in the archival fragments, are testament to the courage, adaptability and quiet triumph of a people who refused to be erased.

References

Slave Registers for:

- John Aerstin from 1817, 1818, 1819, 1821, 1822

- Catherine Aerstin 1817, 1821

- Elizabeth Aerstin 1821, 1834

- Sarah Aerstin 1824

- George Cruikshank 1825

- William Pitt 1820

- Richard Warren 1819

- Matilda Warren 1820, 1821, 1825, 1829, 1834

- Samuel Weatherhead 1827

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society for his editorial support