Eleanor Alder

Fact File: Eleanor Alder

Claim Number: 156

Compensation Award: £61 18s 6d

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 3

Parish: St. George

Parliamentary Papers: p. 95

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eleanor Alder

Eleanor Alder appears in the Grenada compensation records as a small-scale enslaver who was based in the parish of St George and held three enslaved people at the time of emancipation. She submitted Claim No. 156 and received £61 18s 6d when slavery was abolished, an amount reflecting both the limited size of her holding and the intimate household-based nature of her reliance on enslaved labour. She would have held the enslaved to work in her household, in a business or even rented their services out. In any event, records suggest a woman of modest means, and her own signature in the Slave Registers was a simple cross which indicates that she was illiterate. This detail offers a glimpse into her social position: a woman who occupied authority over others while lacking the literacy and formal education that many plantation and business proprietors possessed. So, it is most likely she used the enslaved for her own purposes.

It would seem that Eleanor depended on just two enslaved women to keep her household running, Elsey (sometimes called Alice) and Phillis, with the addition of Mary Louise until she was sold to Lawrence Von Weiller in 1821. It was a small group, but their hard work was what kept everything going. They almost certainly were working within a domestic capacity rather than in a field-based plantation setting. Eleanor’s daily life and social standing were shaped by their constant presence and work. Their labour would have included cooking, cleaning, carrying water and tending to the house.

The registers show that Eleanor managed a shifting enslaved household across nearly two decades of reporting, selling Mary Louis in 1821 and recording the birth of Fancheon to Elsey in 1826. These transactions reveal how even small-scale enslavers used sale, purchase, and reproduction as mechanisms for maintaining their labour force. By 1834, on the eve of full emancipation, Eleanor Alder still held three enslaved persons; an adult woman approaching old age, a young woman at the height of her strength, and a child whose lives and relationships had become deeply entwined with the rhythms of her household. Her story, though modest in scale, forms part of the wider picture of small female enslavers in Grenada whose domestic settings were nonetheless sustained by exploitation, and the legal ownership of other human beings.

What was Eleanor’s racial identity?

We have found no record that explicitly states Eleanor Alder’s colour or racial identity. However, when we place all the available evidence side by side and consider the social structure of early-nineteenth-century Grenada, one conclusion becomes significantly more likely than the others. She was most likely white.

Several factors support this interpretation.

- She owned multiple enslaved women.

- She was illiterate and signed the registers singularly herself. From this, we can assume that she was the head of the house (there is no record of her marital status). She may have inherited the means to acquire the workers from a former spouse or other inheritance.

- She traded with a white man for the sale of Mary Louise.

That said, “free coloured” in St George did own small numbers of enslaved people, and illiteracy was not uncommon among them. However, this occurred less often before the 1830s and there would be other clues to ethnicity in parish or manumission records, none of which have surfaced for Eleanor.

Also, a formerly enslaved and single woman owning multiple enslaved women herself was less common. Although, it must be remembered that many of these women had "relationships" with white men who may have provided the means to own property, including enslaved. Still, nothing in the registers suggests that Eleanor had recently transitioned from enslavement to freedom, and socially she operated firmly within the enslavement system.

------------------------------------------------------------------------- .

The Enslaved

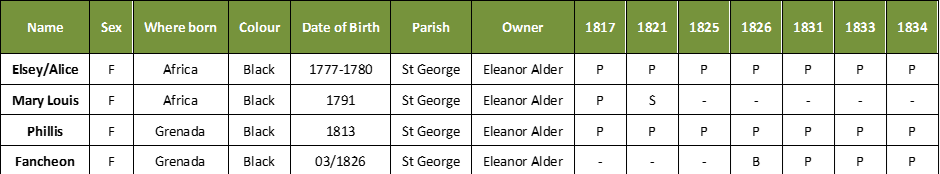

Records from the Slave Registers by year

Key: B = Born, P = Present, S = Sold

The people Eleanor Alder enslaved; Elsey (also recorded as Alice), Mary Louis, Phillis, and Elsey’s daughter Fancheon, form a small but emotionally powerful enslaved community shaped by intergenerational bonds, forced labour, and the insecurity of sale and separation. Their stories, as recovered from the Slave Registers, reveal the intimate scale of domestic enslavement in Grenada and the resilience of women who lived through displacement, childbirth, and the unrelenting control of an owner’s household.

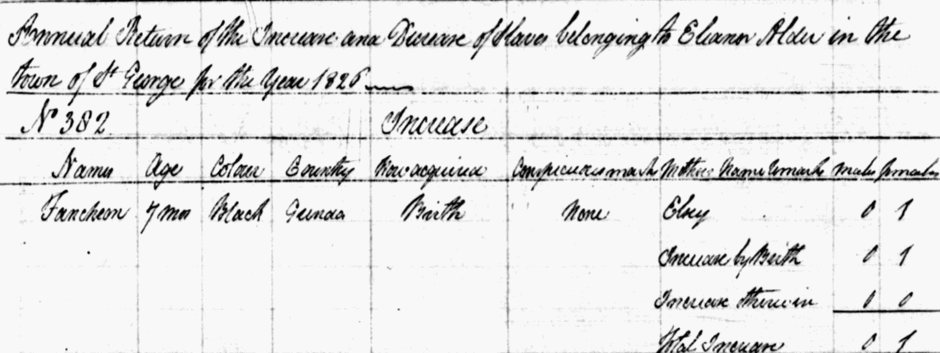

Elsey and Fancheon

Elsey, born in Africa between 1777 and 1780, was the anchor of this enslaved group. By the time she first appeared in the 1817 register she was already a mature woman, forcibly removed from her homeland decades earlier and likely carrying memories of her original language, culture, and family. Over the years she was consistently recorded, always present, always serving suggesting that she was Eleanor’s most relied-upon worker. Late in life, in 1826, she gave birth to her daughter, Fancheon, showing both the exploitation of enslaved women’s reproductive bodies and the strength of a woman who became a mother again in her late forties.

Fancheon grew up entirely within the confines of the Alder’s affairs, her earliest years spent in servitude and likely shadowing her mother’s tasks within the household.

Fancheon was recorded from infancy through to age eight during the final years of slavery. Born into a system already beginning to collapse, she represented the last generation of enslaved children under Alder’s control. Her early years were shaped by her mother Elsey’s labour and by the enforced intimacy of a tiny enslaved household where the boundary between childhood and servitude was thin and shifting.

Who was Fancheon’s father?

Records do not name Fancheon’s father, but several clues help us understand what is most likely. Fancheon was born in March 1826 to Elsey, an African-born woman in her late forties. Both mother and daughter were recorded as Black, and there were no enslaved men listed on Eleanor’s property at that time. This means that Fancheon’s father cannot have been an enslaved man belonging to Eleanor, since her small household consisted only of enslaved women. The father must therefore have come from outside of this setting.

In early nineteenth-century Grenada, when a small domestic enslaved household contained only women, the majority of children born under these circumstances were fathered by free men living or working nearby. These men were most commonly white or free coloured and had social, economic, or physical access to the household. In an environment where enslaved women had no legal rights over their bodies and were routinely exposed to coercion, such paternity was seldom the result of an equal or consensual relationship. Elsey’s advanced age at the time of Fancheon’s birth strengthens this interpretation.

It is possible that the father was an enslaved man from a neighbouring urban household, since Eleanor lived in St George’s where domestic properties stood close together. Enslaved men working as grooms, tradesmen, or hired labourers often moved between properties. However, African-born enslaved women in their late forties rarely entered consensual relationships with enslaved men, especially when no enslaved men were present in their immediate domestic environment. Pregnancies at this age were far more often the result of sexual exploitation by free men with authority or proximity.

The social realities of Grenada at the time strongly suggest that the father was a man from outside the household, very likely a free man who had the power to exploit Elsey’s position.

Phillis

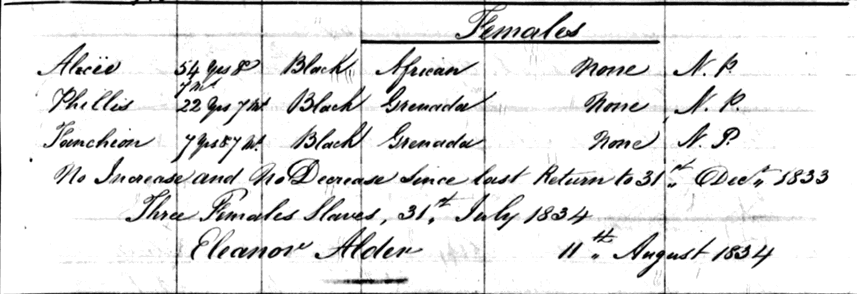

Phillis, born in Grenada in 1813, grew into adolescence and adulthood while still enslaved by Eleanor Alder. By the time emancipation arrived in 1834 she was twenty-one and would have been indispensable to the household’s labour.

The surviving registers do not explicitly identify her mother, but the available evidence allows us to make a strong and well-reasoned assessment. Phillis appears consistently on Eleanor Alder’s property from 1817 through to emancipation. At the time of her birth, the only African-born women under Alder’s control were Elsey and Mary Louise. Both women were of childbearing age in 1813, making either a possible mother. Elsey would have been in her mid-thirties, while Mary Louise would have been around twenty-two.

It is also possible that she was bought as a child before she reached 4 years old.

The relationship between Phillis and the other enslaved women offers important clues. Phillis remained with Elsey across every slave register, through changes in ownership and household structure. When Mary Louise was sold to Lawrence Von Weiller in 1821, Phillis did not accompany her. In small domestic enslaved households like Eleanor Alder’s, mothers and young children were generally kept together unless a deliberate decision was made to separate them. The fact that Phillis stayed while Mary Louise was removed suggests that they were not regarded as a mother-and-child pair. In contrast, Phillis grew into adulthood alongside Elsey and later with Fancheon, forming the kind of intergenerational domestic unit characteristic of enslaved family groups centred on a matriarch.

Elsey’s later childbirth further strengthens the likelihood that she was Phillis’s mother and may have been fathered by the same man.

Marie Louise: From Africa to Emancipation – A Life Traced Through the Registers

Mary Louis, also born in Africa suggested around 1791 (there are no records to confirm the date of birth). She appears in the 1817 register as a young woman in her twenties, sharing with Elsey the experience of forced migration and loss. Her life took a different path in 1821 when she was sold to Lawrence Von Weiller, a transaction that demonstrates how easily family-like bonds within small enslaved households could be broken. It is possible that she was the mother of Phillis, who appears as a young Grenadian-born girl in the registers, though it is more likely that Phillis was Elsey’s child.

Marie Louise’s life is one of the rare stories we can follow across more than two decades of Grenada’s slave registers. She was an African woman whose presence is recorded with remarkable consistency from 1821 through to emancipation in 1834. Her life reveals the instability of enslavement, the emotional and physical endurance of African-born women, and the shifting household fortunes that shaped the fate of the enslaved.

Early Life and Sale in 1821

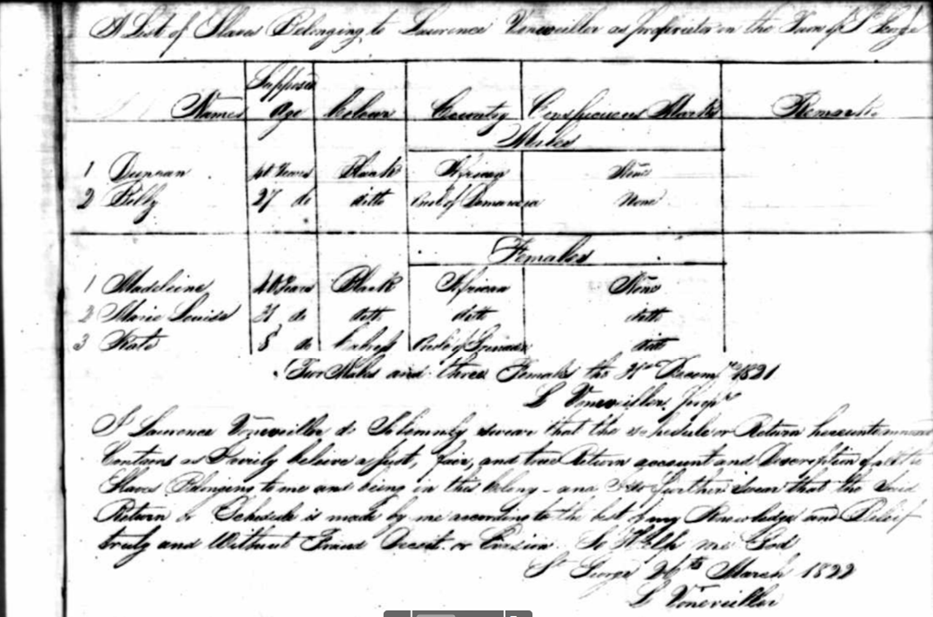

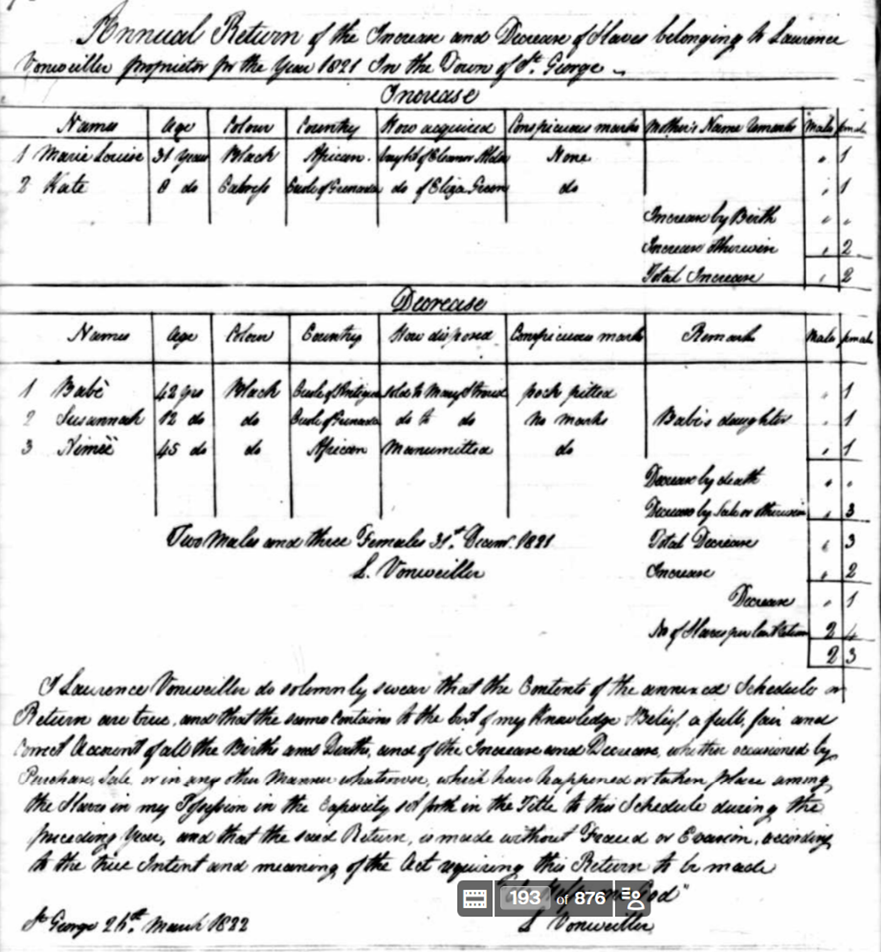

Marie Louise was forcibly transported from Africa to Grenada during the later years of the slave trade. By 1821, aged about 31, she was enslaved by Eleanor Alder, living in a small domestic household where she worked alongside one or two other enslaved women. That year, Eleanor sold her to Lawrence Von Weiller, a transaction that uprooted her from a familiar yet coercive environment and relocated her into the domestic orbit of a new enslaver at a pivotal moment.

- Note: Lawrence Von Weiller was a free coloured man of mixed African and French heritage. He was charged but pleaded and was found not guilty for his involvement in Fedon's Rebellion 1795-1976 and was discharged. He was one of those who had surrendered. He owned a plantation in St Andrew.

Here, she joined Duncan and Madeline also from Africa, both aged about 40, Billy (27) from Demarara and a mixed race girl called Kate (5) who was born in Grenada.

1821 is also the year when Lawrence Von Weiller manumitted a 45 black African woman called Nimee. For Marie Louise, this must have been a moment of mixed significance. On the one hand, entering a household where manumissions occurred may have offered some hope of being released at some stage. On the other, she may just have been a replacement for Nimee. Whatever its meaning, this episode places her life at the intersection of hope and pragmatic exploitation.

Transferred by Will After Lawrence’s Death (1825)

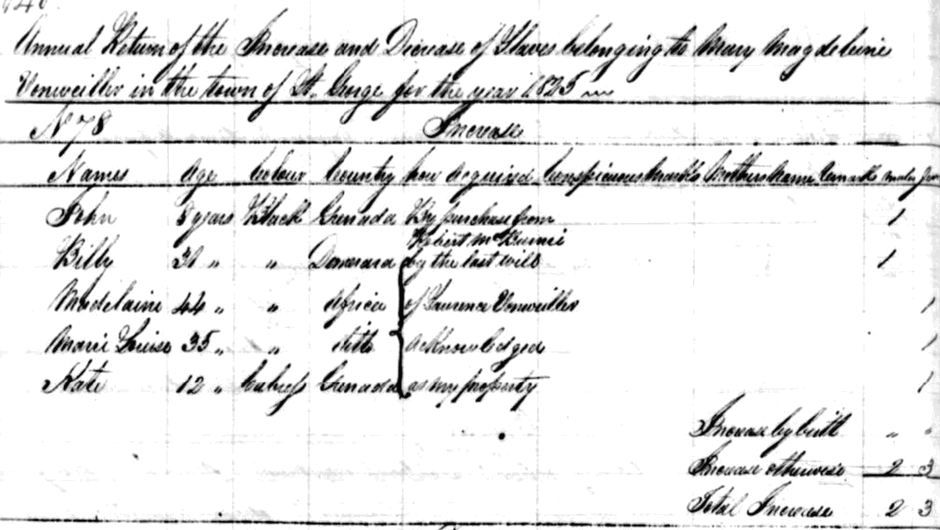

By the 1825 Slave Register, Lawrence had died. Marie Louise, then aged 35, was inherited by Mary Magdeleine Von Weiller, likely Lawrence’s widow or daughter. She was bequeathed to Magdeleine together with Billy (31), Madelaine (44) and Kate (12), who she knew from her time with Lawrence. She was also joined by John (8) who had been purchased from Robert McBurnie.

She was bequeathed to Magdeleine together with Billy (31), Madelaine (44) and Kate (12), who she knew from her time with Lawrence. She was also joined by John (8) who had been purchased from Robert McBurnie.

This very act of being willed as property and having to move without choice illustrates the brutal legal reality governing her life. Even in death, enslavers retained the right to direct the future of the enslaved, severing them from potential manumission and re-embedding them into new authority structures without their consent.

The 1829 Slave Register records Marie Louise again, this time aged 39, still owned by Mary Magdalene together with Madeleine and Kate

The three appear to have formed a small, stable domestic unit. Their ages and origins suggest a multigenerational household: two African-born women in mature adulthood and one younger Grenadian-born girl entering her mid-teens. The fact that there were no increases or decreases from the last register in Mary Magdalene’s household would indicate that John and Billy left soon after they were acquired. Still Enslaved in 1834: The Final Register Before Emancipation

The 1834 register, the last before full emancipation, lists Marie Louise again, now aged 43½ years. Madeleine (32½) and Kate (20) were still there too, forming a tight-knit trio whose lives had become deeply intertwined after years of shared forced labour.

To be recorded in 1834 means Marie Louise lived to see the legal end of chattel slavery in Grenada. She entered the island as an enslaved African girl or young woman and survived into the new era of apprenticeship. This is an extraordinary arc of endurance for someone who had already survived the Atlantic crossing, sale, inheritance, and decades of coerced labour.

What This Reveals About Her Experience

- Marie Louise’s life story, reconstructed from careful archival tracing, becomes a powerful testament to the lived experience of African-born women who endured and adapted across major transitions:

- She survived the Middle Passage.

- She was sold at least once, inherited once, and never freed before 1834.

- She lived in three consecutive enslavers’ households.

- She forged long-standing bonds with other enslaved women, especially Madeleine and Kate.

- She remained stable in one household long enough to reach emancipation alive

This was a remarkable outcome given the mortality rates for African-born enslaved people. Her story, preserved across multiple returns, gives us one of the clearest examples of an African-born Grenadian enslaved woman whose life spanned the system’s final decades and ended in the moment of its collapse.

Summary

Although Eleanor Alder was neither wealthy nor part of the large planter class, her possession of three enslaved women makes sense once we consider the nature of labour in domestic settings in early nineteenth-century Grenada. Households like hers relied entirely on human labour for every aspect of daily life. Enslaved women performed a wide range of tasks that today would be divided among several occupations, and their roles were physically demanding, continuous, and often required overlapping skills and constant availability.

A single householder, especially an illiterate woman without a husband—depended on enslaved women to run her entire domestic world. Household labour included cooking over open fires, washing clothes by hand, fetching large quantities of water (as there were no pumps in most domestic settings), cleaning, tending small gardens or kitchen plots, preserving food, carrying goods to market, and sometimes producing items for sale. In addition, enslaved women cared for livestock, fetched firewood, and assisted with small-scale agricultural tasks if the property had provision grounds or cash crops. A lone enslaved woman could not reasonably sustain all of this work, particularly as many tasks had to be done simultaneously.

Age was another factor. Elsey, the African-born woman under Alder’s control, was already in her late thirties or early forties when the registers began and later reached nearly fifty. Older enslaved women were usually the most experienced and trustworthy, but physically they could no longer shoulder the heaviest work alone. Eleanor would have required a younger woman, such as Phillis, to take on strenuous duties. When Phillis was a child, Eleanor still required a second adult, which explains the presence of Mary Louise in the early years. In small households, enslaved children could not contribute meaningfully until they were older, making an additional adult woman necessary to maintain day-to-day operations.

Domestic settings also needed continuity. Illness, pregnancy, or injury could leave a household without labour, so enslavers often kept two or three women to ensure that essential work continued uninterrupted. With no enslaved men under Alder’s control, the women may also have been responsible for tasks that mixed-gender enslaved households usually shared. In this sense, the three women functioned as a complete labour unit: one older, experienced matriarch; one younger woman becoming the main labourer; and, eventually, a child growing into work roles as she matured.

Finally, the presence of three enslaved women reflects the social expectations of the time. Even modest white women in St George often owned multiple enslaved people because it was seen as a marker of respectability. Domestic labour was not only a necessity but also a symbol of status. Eleanor’s reliance on enslaved women allowed her to sustain the appearance and functioning of her interests, even if she herself lacked literacy, wealth, or broader social power.

Together, the enslaved workers under Eleanor Alder’s control formed a small but resilient community. There were African-born elders holding memory and trauma, Grenadian-born daughters inheriting both burden and strength. Their labour sustained the Alder household, their relationships gave them emotional survival, and their presence reveals how even small households were sites of coercion but also endurance, and intergenerational resilience.

References

Slave Registers for Eleanor Alder from 1817, 1821, 1825, 1826, 1831, 1833, 1834

Slave Registers for Lawrence Vonweiller from 1821 (and another from the same year)

Slave Registers for Magdelaine Vonweiller from 1825