Mary Urseal Allan

Fact File: MARY URSEAL ALLAN

Claim Number: 182

Compensation: £20 12S 10D

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1

Parish: St George

Parliamentary Papers: P. 95

Family

Little is known about where she was from or even her ethnicity. However, she may have been the Mary Allan who married William Wellington in St George in 1827. A notice of the wedding was posted in the St Georges Chronicle And Grenada Gazette 26 May 1827.

This public notice of her marriage is significant as it strongly suggests that Mary Allan was socially recognised within the white colonial community. Newspapers of this kind routinely reported marriages of white and elite “free coloured” residents, but interracial marriages were exceptional, and likely framed with explicit racial descriptors. The absence of any qualifying language in the notice points to a marriage considered socially unremarkable, most consistent with both parties being white.

Business Interests

Mary Urseal Allan emerges from the records as a modest but telling figure within the domestic landscape of slavery in urban Grenada, her life illustrating how enslavement permeated even small households beyond the great plantation estates.

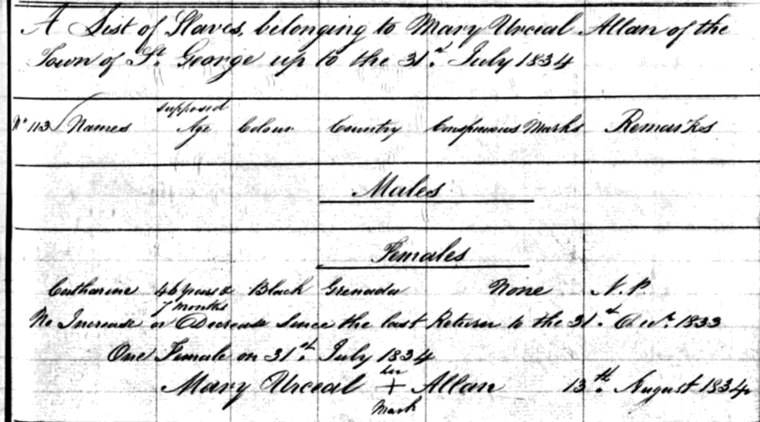

She lived in the parish of St George, where she was recorded as the owner of a single enslaved woman, Catherine. Catherine had been born enslaved in Grenada in 1787 and appears consistently in the island’s slave registers up to 1834. By the final register, Catherine was 47 years old, suggesting a lifetime spent in bondage. Given the scale of Mary Allan’s household, Catherine was almost certainly employed as a domestic worker, responsible for the daily labour that sustained Mary’s domestic life rather than plantation production.

Mary would have grown to be very reliant on Catherine’s services.

Compensation claim

Mary Allan’s claim for compensation following the abolition of slavery reflects this small-scale ownership. Under claim number 182, she received £20 12s 10d for the loss of Catherine’s labour. Though a relatively small sum compared to major estate awards, it nonetheless places Mary firmly within the compensation system that prioritised enslavers’ financial interests while offering nothing to the formerly enslaved themselves.

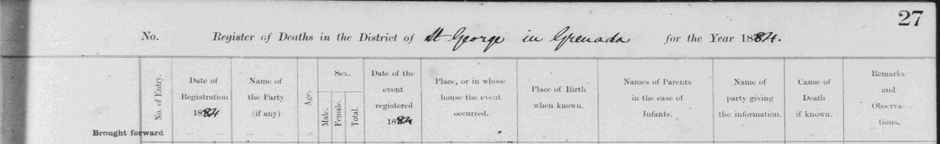

Death

There are no conclusive records of her civil record, however, she may be the Mary Allan recorded as having died on 7 February 1884 in Upper Monserrat (now Upper Lucas Street), St George’s, aged 82. If so, she lived through the profound transformation of Grenadian society from slavery, through apprenticeship, to full emancipation and beyond.

The cause of death was given as senile debility. At this time, senile debility was a catch-all medical diagnosis used by doctors and registrars to describe death resulting from old age and gradual physical decline, rather than from a single identifiable disease. It literally meant a weakening (debility) associated with advanced age (senile), and it was commonly applied to elderly people whose bodies had slowly failed. It was often used where someone had lived to what was considered a respectable old age and had declined gradually. In Mary’s case, dying at around 82 years old in Grenada would have been regarded as exceptional longevity for the period, particularly in a tropical climate.

The Enslaved

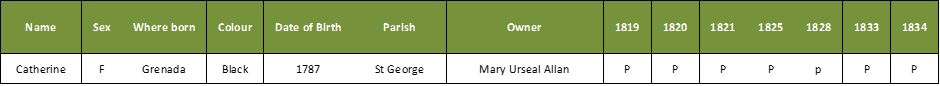

Record from Slave Registers

Key P=Present

Catherine was the only enslaved person registered by Mary who, by signing her name with an “x”, indicated that she was illiterate. Catherine was born enslaved in Grenada and appears on the Slave Registers from 1819 to 1834 when she likely was retained during the apprenticeship period and finally released in 1838 age 51 years old.

Catherine would have emerged from enslavement as a woman of considerable experience and resilience. By the time she was finally released in 1838, at around 51 years old, she had survived childhood enslavement, decades of domestic labour, and the upheaval of the apprenticeship system. Women like Catherine carried with them highly valued skills: cooking, laundering, childcare, household management, and intimate knowledge of urban life in the Town of St George. This expertise would translate directly into paid work after emancipation.

It is very likely that Catherine continued working as a domestic labourer, either for wages or in exchange for housing, food, or other support. Many formerly enslaved women remained in the same households where they had worked previously, but now as paid servants, negotiating terms that gave them far greater autonomy than before. So, it is possible that Catherine chose to stay with Mary. Others moved between households, offering their services independently and choosing employers who treated them with respect or who were connected through church or community networks.

Catherine may also have become part of Grenada’s emerging free Black community, building relationships beyond her Mary’s household. Churches played a crucial role at this time, (Catholic predominantly, but for Free Coloureds and Black people this was especially the Methodist church), which provided spiritual support, social networks, and sometimes schooling for children and adults alike. Women of her generation were often central figures within these networks.

At her age, Catherine may also have taken on a mentoring or caregiving role, looking after younger women or children, passing on skills and knowledge shaped by lived experience. In many post-emancipation households, older women became anchors of stability and widely respected figures.

Most importantly, Catherine lived her final years as a legally free woman. She could choose where to live, whom to work for, how to spend her time, and with whom to form family or community bonds. Even if material conditions remained hard, this freedom represented a profound and meaningful transformation.

Catherine’s life, traced across the registers from 1819 to 1834, is therefore a record of survival and a quiet testimony to endurance, skill, and dignity in freedom. Like many women of her generation in Grenada, she helped to lay the foundations of post-emancipation society.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support.