John Aitcheson

Fact File: John Aitcheson (Senior)

Parish: St. Andrew

Life dates: 1705-1780

John AITCHESON Jnr (- 1770)

John AITCHESON Jnr. of Rochsolloch, Airdrie, Scotland, purchased Belmont Estate in 1764 after the French ceded Grenada to the British following the Treaty of Paris (1763), which ended the Seven Years' War. Belmont Estate had previously been under French ownership since the late 1600s and was owned by the Hervier and then Bernege families under the French. After the island became a British colony, Aitcheson Jnr. acquired the estate as part of the wave of British land acquisitions that followed the transfer of colonial power.

In 1764, the same year he purchased Belmont Estate, Aitcheson Jr. signed a petition to King George III. This petition protested instructions given to Governor Robert Melville that would undermine the privileges of the local representatives in the island’s governance. This act suggests that Aitcheson Jnr. was concerned about political representation and the rights of property owners in Grenada, particularly British landowners, during the transition from French to British rule. He continued to sign other petitions throughout the 1760s, further indicating his engagement in the political dynamics of the island at the time.

Although details of his managerial approach to Belmont Estate are limited, the fact that he bought the property as soon as the island changed hands places him firmly among the ambitious Scottish investors who expanded plantation interests across the Caribbean during this period. The Belmont Estate history notes that Aitcheson Jr. died young, leaving no long career on the island. With his death, ownership passed to his father, John Aitcheson Sr. Even in his short tenure, however, Aitcheson Jr.’s involvement in local political petitions reveals him as part of the early British planter elite attempting to influence governance at a moment of rapid colonial change.

Aitchison Jnr bought plots of land next to the Belmont estate that became the Tivoli estate with Alexander Campbell (1739-1795), He also bought “Bloody Bay” lots 8 and 9 in the Northeastern Division (later St John) in Tobago.

He sold the Tivoli estate together with 200 enslaved workers to John Fordyce, Andrew Grant, Robert Malcolm and William Trotter of London merchants and partners on 30 August 1767. There was also a schedule for 90 slaves on the Belmont estate.

Aitcheson Jnr died on 31st May 1770 in the US.

John AITCHESON Snr (1705-1780)

After Aitcheson Jnr died, his father, John AITCHESON Snr., inherited Belmont Estate. Unlike his son, Aitcheson Snr. was largely an absentee landlord, meaning that he did not live on the estate or take part in its daily management. He leased the estate for 13 yrs at a price of £2520/yr to Alexander Campbell, former partner of Aitchison, Jr. and owner of the neighboring Tivoli estate.

This was a common arrangement among British plantation owners in the Caribbean, who often resided in Britain while managing their estates through local overseers or managers.

Belmont Estate, like many plantations in Grenada, was originally focused on sugarcane and coffee, with sugarcane being processed on-site into molasses. This was a common practice on Caribbean plantations, where sugarcane was grown, harvested, and processed into sugar, molasses, and rum. The ruins of the watermill on the estate today testify to the intensive agricultural and processing activities that took place there. Over time, crops like cotton, cocoa, nutmeg, and bananas became important to the estate’s production.

In 1770, Aitcheson Snr. leased Belmont Estate to Mr Campbell. The lease was for a period of 13 years at a considerable annual price of £2,520, indicating that Belmont Estate was a highly valuable property.

He also sold the land at Bloody Bay in Tobago to Campbell.

In 1780, Aitcheson Snr. left Scotland for Grenada and died shortly after his arrival at Belmont Estate on May 31, 1780, at age 75. He was buried in the estate’s cemetery, and his grave can still be visited today.

The Aitchesons’ involvement in Belmont Estate is a reflection of the broader British colonial presence in Grenada during the 18th century. Their ownership and leasing of the estate show the patterns of landownership, absenteeism, and the use of plantations for the production of cash crops, which were central to the colonial economy of the Caribbean. This system was built on the labour of enslaved Africans, and plantations like Belmont would have been reliant on this form of labour until the abolition of slavery in the 19th century.

While John AITCHESON Jr. was briefly active in local politics, his early death and his father's absenteeism meant that Belmont Estate’s direct management was likely left to overseers or lessees like Alexander CAMPBELL, who had a significant role in running the plantation during the lease period.

Following the death of John AITCHESON Snr., Belmont Estate passed to his eldest daughter Bethia, as per his will. She was instructed to sell the estate and distribute the proceeds among herself, her sisters, Margaret and Isabella and their cousin Gilbert HAMILTON, a Glasgow merchant.

It was sold to Robert Alexander HOUSTON, a member of a prominent Scottish family involved in the sugar trade, based in Clerkington, East Lothian. It was a prime property. The 276 acre sugar plantation estate including the enslaved workers, animals, land and buildings was sold for £21,356 (equivalent to about £1.5M today). However, this value was built on the exploitation of enslaved labour, a grim reality that defined the region’s colonial economy.

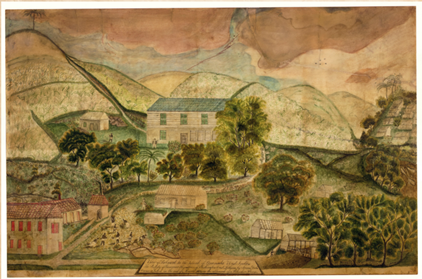

One of the notable individuals connected to Belmont Estate was James Dodds, a former overseer who was also an amateur painter. In 1821, Dodds painted a watercolour depicting the central part of Belmont Estate, providing a visual representation of the plantation, including its enslaved workforce. This painting is now preserved at the estate and serves as an important historical artifact, offering insight into the estate’s layout and the daily lives of those who lived and worked there.

Reproduced from Our History – Belmont Estate (belmontestategrenada.com)

Reproduced from Our History – Belmont Estate (belmontestategrenada.com)

Legacy The Aitchesons’ legacy from owning enslaved people lies in how their wealth, property, and family advancement were created, consolidated, and transferred through slavery-based plantation economies during a formative period of British rule in Grenada

John Aitcheson Jr.’s legacy is rooted in expansion and consolidation. By purchasing Belmont Estate in 1764 immediately after Grenada passed from French to British control, he positioned himself among the first wave of Scottish investors who capitalised on imperial transition.

His ownership extended beyond Belmont to adjacent lands that became Tivoli Estate and to enslaved-labour estates in Tobago, including Bloody Bay. The sale of Tivoli together with around 200 enslaved people in 1767, alongside a schedule of approximately 90 enslaved people at Belmont, demonstrates that enslaved men, women, and children were treated as liquid capital, transferred alongside land to fuel merchant partnerships in London and Glasgow.

His political petitions in the 1760s, framed as defending representative rights, were closely aligned with protecting planter property interests, including the ownership and control of enslaved labour. Although he died young in 1770, his brief career helped embed Belmont and associated estates within a transatlantic commercial network sustained by slavery.

John Aitcheson Sr.’s legacy is one of absentee extraction and intergenerational transfer. After inheriting Belmont, he managed it largely from Scotland, leasing it at high annual rents that reflected the estate’s profitability under enslaved labour. The wealth he accumulated was managed by overseers, lessees, and the coerced labour of enslaved people whose lives sustained production. When he died in 1780, the estate, including enslaved people, buildings, livestock, and machinery, was valued at over £21,000, a substantial fortune that flowed directly into family inheritance.

His will ensured that the proceeds of slavery were redistributed among daughters, sisters, and a Glasgow merchant nephew, demonstrating how slavery underpinned family security, status, and commercial continuity in Britain.

Crucially, While both father and son were involved in the slave trade, both had died before the Abolition Act and so could not claim compensation. Robert Houston went on to claim for the loss of 194 enslaved people and received £5024 8s 11d. This absence of compensation does not diminish their legacy but highlights an earlier phase of slavery in which wealth was realised through land sales, leases, and merchant partnerships rather than state payouts. The estate’s later sale price, achieved after decades of enslaved labour under successive owners, was built on foundations laid during the Aitcheson period.

For the enslaved people of Belmont, Tivoli, and associated properties, the Aitchesons’ legacy was one of displacement, commodification, and invisibility.

Enslaved individuals were counted in schedules, mortgaged, leased, and sold, but rarely named in surviving records. Their labour enabled the Aitchesons’ rise, sustained absentee wealth, and underwrote the prosperity passed on to descendants and business associates in Scotland and London.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support.

References

http://www.belmontestate.net/grenada-history.htm

Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook post

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/863110984