Charles and John Alexander

Fact File:

Charles Alexander John Alexander

Claim Number: 742 Claim Number: 743

Compensation: £34 8S 0D Compensation: £34 8S 0D

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1 Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1

Parish: St Patrick Parish: St Patrick

Parliamentary Papers: p. 99 Parliamentary Papers: p.99

Life dates: 1802-1861 Life dates: 1798-1840

Charles Alexander

Charles was born on 5th December 1802 into a long-established Scottish family from the historic county of Banffshire which is now split between Aberdeenshire and Moray council areas.

He was the eldest son of Charles ALEXANDER (1761-1845) and grandson of Charles ALEXANDER (1717–1787) who fought alongside Bonnie Prince Charlie during the Jacobite uprising of 1745 and a descendant of the original "Lord of Lochaber", Alexander (or Alastair Carrach) MacAlister who was a member of the Clan Donald and a prominent Highland figure. Alastair’s descendants adopted the surname "Alexander," eventually becoming a distinct branch of Clan Donald. This lineage includes the Alexanders of Inverkeithny.

The Lordship of Lochaber was known for its warrior legacy, including Alastair's reputed invention of the Lochaber axe, a weapon used in Scottish battles during that period.

After the defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, many Highland families, including the Alexanders, experienced significant political and economic upheaval. The Alexanders faced severe financial hardships as a consequence.

Grenada

As a result of these hardships Charles migrated to Grenada around 1838 with his brothers, Richardson and Hall, in an effort to restore the family's financial stability. Even though this was the year of emancipation, he had enslaved people previously as an absentee landlord. He had 2 other brothers Thomas and John who both died in Grenada; Thomas on 6th Mar 1819 (age 18) and John 1840 (age 42). Their uncle Thomas Thain's involvement with the North West Company of Canada may have influenced their decision to pursue opportunities in the Caribbean.

Settling in Grenada, Charles became a successful plantation owner but he had arrived at a time after emancipation where workers started to assert their rights and demand better treatment, conditions and pay and this applied to the “liberated Africans” who were brought to Grenada after emancipation.

Charles organised a substantial militia drawn from the planter community to subdue such protestations from the liberated Africans. He personally commanded this unit and was credited with restoring stability during what was described as a period of threatened disturbance.

This was a significant development because it marked a clear transition from slavery to post-emancipation control, rather than a break with the past. It reflected deep planter anxiety about maintaining order in a society where formerly coerced labour was no longer legally enslaved but still expected to remain disciplined and compliant.

The resistance of the “liberated Africans” was perceived by colonial elites as a threat to economic stability and social hierarchy. By organising a militia drawn from the planter class and personally commanding it, Charles Alexander positioned himself as a defender of colonial authority at a moment when the old mechanisms of control had weakened.

In recognition of these services, Queen Victoria granted him a Colonel’s commission, a significant honour for a colonial resident and indicative of his standing within Grenadian society. He shortly afterwards became a member of the Executive Council placing him at the centre of colonial governance during a turbulent era that included the aftermath of emancipation and evolving economic pressures across the Caribbean. It demonstrated how men already embedded in slavery and slave management could reinvent themselves as guardians of peace and governance, preserving their influence and status in the new era.

Charles and his brothers frequently returned to Scotland, keeping close ties to the old home. After their father’s death in 1845, Charles acquired Don Bank Cottage near the mouth of the River Don in Old Aberdeen, where his mother Helen Thain lived until her death in 1858. Their father Charles ALEXANDER died at Auchininna at age 84, ending over 200 years of family residency.

Compensation Claims

Charles made a claim for just one enslaved person with compensation awarded of £34 8s 0d. His brother John was awarded an identical amount for the one person he had enslaved.

It would appear that Charles later acquired the Montreuil estate as it was left in trust for his son Douglas after he died. They also acquired the neighbouring estate at Springbank.

Montreuil estate was later overseen by family member Arthur Henry Beckles Gall. Over time, ownership of the estate became fragmented among Charles ALEXANDER’s descendants. By the mid-1960s, few family members still lived in Grenada, and ownership was divided among 22 descendants, only six retaining the Alexander surname.

In 1967, the estate was producing cocoa, nutmeg, mace, bananas, and other provisions, yielding an income of EC$49,986, though production and income declined by the early 1970s. Estate land had to be sold to cover operating costs, reducing the estate from about 300 acres in 1970 to 211 acres after selling over 89 acres.

Family

His personal life was equally rooted in networks that tied Scotland and the Caribbean together. On 15 December 1840 he married Margaret Drysdale Douglas, born in 1819, daughter of Andrew Douglas of Jedburgh and Berwick-upon-Tweed. The couple had eleven children; five sons and six daughters. Two of their sons died young, a common tragedy of the era. These included:

- Charles Douglas ALEXANDER 1841–1842

- Arthur Harvey ALEXANDER25 Feb 1843–30 Dec 1905;

- He was a bursar at Aberdeen University

- He served as the Agent General of Immigration, a Member of the Executive Council, and Colonel commanding the Militia in British Guiana.

- He married Isabella Bibson on July 25, 1867.

- They had four sons and three daughters. His sons included Major Arthur Charles Bridgeman Alexander, Captain George Hamilton Alexander, Major D’Arcy Duncan Alexander, and Edward Harvey Alexander. His daughters were Annie Alexander, Helen MacKenzie Alexander, and Margaret Florence Drysdale Alexander.

- He had a notable military career, with all four of his sons following in his footsteps and serving in the army.

- After returning to his ancestral country, he settled in Haselwood near Craigellachie. He passed away suddenly on December 30, 1905, at Canfield Place, Hatfield, and was buried in the cemetery of that town.

- Helen ALEXANDER1844–1924;

- Helen was a twin

- She married Arthur Gall in 1868, who was an officer of Constabulary in Barbados.

- They had four children:

- Arthur Henry Beckles Gall: Born in 1870, he became a successful planter and married his cousin, Edith Gall, in 1899.

- Herbert Frederick Douglas Gall: Born in 1875, he became the Agent and General Manager of the Colonial Bank. He married Aileen Duke in 1921 and had two daughters, Cynthia Helen and Clara Joyclyn.

- Ida Gall: Born in 1872, she married Patrick Archibald Fletcher MacLeod in 1900 and had one son, Colin, and four daughters, Helen, Aileen, Agnus, and Dorean.

- Clarie Gall: Born in 1874, she married Robert Combe of Ceylon in 1902 and had three children: Gordon, Helen, and Clara.

- Helen passed away in Camberley in 1924 at the age of 80.

- Douglas ALEXANDER22 Mar 1849–1910;

- Born at Montreuil Estate, St. Patrick, Grenada.

- Douglas was educated in Aberdeen, Scotland.

- After completing his education, he returned to Grenada to manage his father’s property, Montreuil, which had been left in trust for the family. He successfully managed and improved the estate, ensuring its prosperity.

- Douglas became a member of the Executive Council and owned several estates in Grenada. His contributions to the community were highly valued, and he was known for his sound influence and wise counsel.

- In 1871, Douglas married Annie Elizabeth McEwen, born in 1853. They had eight sons and four daughters. Some of their notable children include:

- Arthur Walter Douglas Alexander: Born in 1874, he became a planter in Grenada and married Edith McLeod.

- Douglas Gordon Alexander: Born in 1879, he served with the South African Constabulary and married Louisa de la Mothe.

- Francis Duncan Thain Alexander: Born in 1881, he was educated at Sutton Valance School in Kent and married Daisy Helen Anne de Gale.

- Harold George Alexander: Born in 1888, he became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons and served in the Indian Medical Service.

- Percy Herbert Alexander: Born in 1889, he served in France during the Great War and married Ellen Gilligan O’Shea.

- Ralph Douglas Alexander: Born in 1891, he served in France during the Great War and married Constance Sharpe.

- Douglas Alexander suffered a severe stroke around June 1904 and was no longer able to manage the estate. He passed away in January 1910 in London and was buried in the same grave as his father at Bow. (This date of his stroke is an estimation because the source doc stated 1944 which is an error as he had died by 1910. 1904 would fit the chronology in the source doc. It explains why he ceased active management of the estate several years before his death, aligns with the six-year period of decline before his final illness and death in London and it is consistent with the obituary, which describes a man who had been in failing health prior to his final operation and death in 1910.)

- Obituary

“It is with profound regret that we have to record the death of Mr. DOUGLAS ALEXANDER of Spring Bank, St. Patrick, news of which was received by cable from London on Saturday. The news came as a painful shock of surprise to his children and numerous friends here, for two weeks had not yet elapsed since the welcome information was received by cable, that he had been successfully operated on for the complaint which he was suffering and was making satisfactory progress. This sad event will cast a gloom over the whole island, for in Mr. Alexander, Grenada loses one of her noblest sons and one of that very rare stamp of men of whom it can be truthfully said; (He never) made an enemy yet never failed to win the friendship of everyone with whom he came in contact, and one who was more highly esteemed and respected the more intimately he was known. Much as his loss will be felt by the community, to the people of St. Patrick's, his death will be a veritable calamity, for in him, they lose a never tiring benefactor and friend and a wise advisor. It is no exaggeration to state that the exceptional prosperity that is being enjoyed by all classes in St. Patrick's is largely due to Mr. Alexander's sound influence and goodness of heart for it is well known that practically every peasant and all but a few of the large proprietors of the parish owe their first start in life to financial assistance rendered by him or to the influence he exercised on their behalf. But perhaps the greatest service rendered to the colony by Mr.Alexander was his timely intervention in the early nineties when through his good influence was wise council the peasantry of St. Patrick's were saved from falling victims to the wave of reckless extravagance which ruined or seriously hampered a large number of peasants in every other parish. Mr. Alexander was born at Montreuil Estate, St. Patrick's on the 22nd of March 1849. He left Grenada as a child and was at school in Scotland when in 1866 the sugar industry finally collapsed and he found himself suddenly faced with the necessity of earning his living and assisting in providing for the support of his five sisters. He volunteered to come out to Grenada to assist the almost impossible task of clearing the family estates of the heavy encumbrances which had accumulated during the protracted sugar crisis. He left England early in 1867 with two of his brothers, both of whom entered the Colonial Service and rose to distinguished positions in Jamaica and Demerara respectively. By careful and wise management, Mr. Alexander not only succeeded in redeeming the family estate but so improved it as to render it capable of providing a comfortable income for his sisters, which they are still enjoying. As a reward for his magnificent achievement he was presented by his brothers and sisters with the portion of the estate known as Spring Bank on which he has since erected a fine residence. By judicious investments and hard work Mr.Alexander also succeeded in amassing a comfortable fortune for himself, yet he has never known to turn a deaf ear to an appeal for any charitable object. Mr. Alexander rendered many years of valuable service on the Legislative Council. Although he seldom took a prominent part in the debates, an expression of opinion from him always carried great weight, for his honesty of purpose and soundness of judgment caused him to enjoy in an unusual degree the confidence of his colleagues on both sides of the table. While tendering the sincerest sympathy of the whole community to the bereaved widow and children who are mourning the loss of a model husband and father, we are able to assure them that their grief is widely shared by the people of Grenada who are also mourning the loss of one of the Colony's most valuable human assets.” - There is also a memorial of Douglas at Bow Cementry.

- Margaret Drysdale ALEXANDER22 Mar 1849–1929;

- Margaret was a twin with her brother Douglas.

- She married Charles Wilfred Neate Hardtman in 1866, who was from an old Huguenot family. Unfortunately, Charles Hardtman passed away three years later, leaving Margaret a widow at 20 years old. She never remarried.

- She devoted her life to supporting and entertaining the numerous progeny of her siblings and was particularly devoted to Douglas’s daughter Emmeline.

- She was known as Aunt Doe

- Thomas ALEXANDER21 Dec 1851– 9 Jun 1925;

- Thomas was the fifth and third surviving son of Charles Alexander and Margaret Drysdale Douglas. He was educated at the Gymnasium in Aberdeen

- Thomas was commissioned in the Military Constabulary in Jamaica in 1872. He participated in various operations and obtained a first-class certificate at the School of Musketry at Hythe in 1879.

- He was awarded the King’s Police Medal and twice acted as Inspector General. Despite being over the age limit, he continued to serve throughout the Great War and retired in 1919, receiving a special letter of thanks from His Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Colonies.

- On March 21, 1877, Thomas married Agusta Hortence, the eldest daughter of the Honorable Robert Nunes, Member of the Governor’s Executive Council.They had two sons and one daughter:

- Robert Donald Thain ALEXANDER: Born on September 29, 1878, he had a notable career as an engineer and served in various capacities in India and Burma. He was also a Lieutenant Colonel in the London Scottish and served throughout the Great War.

- Thomas Patrick Madden ALEXANDER: Born on April 8, 1890, he managed tea estates in Southern India and served in the Royal Air Force during the Great War.

- Emily Elizabeth ALEXANDER: Born on November 26, 1882, she married Denner John Strutt, elder son of Major General John Rootsey Strutt of the Indian Army, and had three daughters.

- His wife, Agusta passed away on April 30, 1921, and was buried in Kingston. Thomas later resided in Tunbridge-Wells, Kent, where he died on June 9, 1925, and was buried in the Borough Cemetery of that town. He was remembered as a very efficient and popular officer, a good cricketer, rider, and shot, and a true sportsman in every sense of the word.

- Charles Alexander 1854–1854

- Rosanna Alexander b.1854

- Emmeline Florence Douglas Alexander b.1857

- Florence Alexander b.1859

- Death

Charles’s final journey home took place in 1861. After decades of work in the West Indies, he sailed back to Britain but contracted pneumonia during the voyage. He died on arrival at the Port of London and was buried in Bow, near the London docks, a poignant ending for a man whose life had been shaped by constant movement between Scotland and the Caribbean. He was 59 years old. Four years later, his wife Margaret also passed away. There are memorials of both of them and their son Douglas at Bow Cemetery. - Richardson ALEXANDER Richardson was the second son of Charles Alexander of Auchininna and Helen Thain of Drumblair and was born on January 25, 1812. Richardson married Mary Morrison in 1862, and they had three children: one son and two daughters. His son, Hall Alexander, was born on November 5, 1867, and became the Chief Engineer of the Steamship Line. His elder daughter, Annie, was born on May 2, 1864, and was tragically killed in a motor car accident along with her brother Hall on August 5, 1911. His younger daughter, Jessie, was born on October 4, 1868, and married Reverend Joseph James Lorraine in 1894. Richardson lived a long life, passing away in Aberdeen on January 18, 1903, at the age of 91, just one day after his wife.

- Hall ALEXANDER Hall was the third son of Charles Alexander of Auchininna and Helen Thain of Drumblair. He was born on June 9, 1818 and married twice. His first marriage was to his cousin Isabella THAINof Drumblain, Inverkeithny, on December 20, 1842. They had three daughters:

- Elsie Thain ALEXANDER (born 1844) - Married Dr. William Lang in 1864 and had thirteen children. She died in 1914.

- Mary Alexander (born 1846) - Unmarried and died in 1926.

- Lillias Alexander (born 1846) - Unmarried and died in 1865.

After Isabella died in 1853. Hall then married his second wife, Isabella Allen, on December 18, 1860. They had four daughters: Isabella Helen Alexander (born December 28, 1861) Edith Gertrude Allen Alexander (Dec 23, 1863 - May 15, 1865) Anne Millicent Alexander (born October 22, 1865) Alice Maude Alexander (born 1868)

Hall died on April 13, 1868, without male issue. His second wife, Isabella Allen, and their family resided in Folkstone.

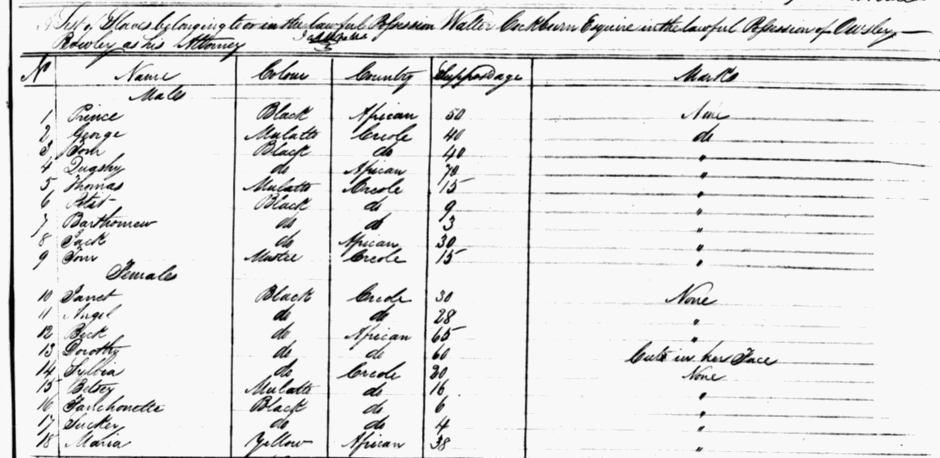

The Enslaved

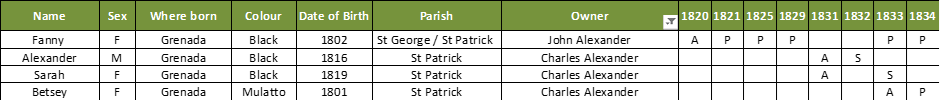

Fanny (1802 -)

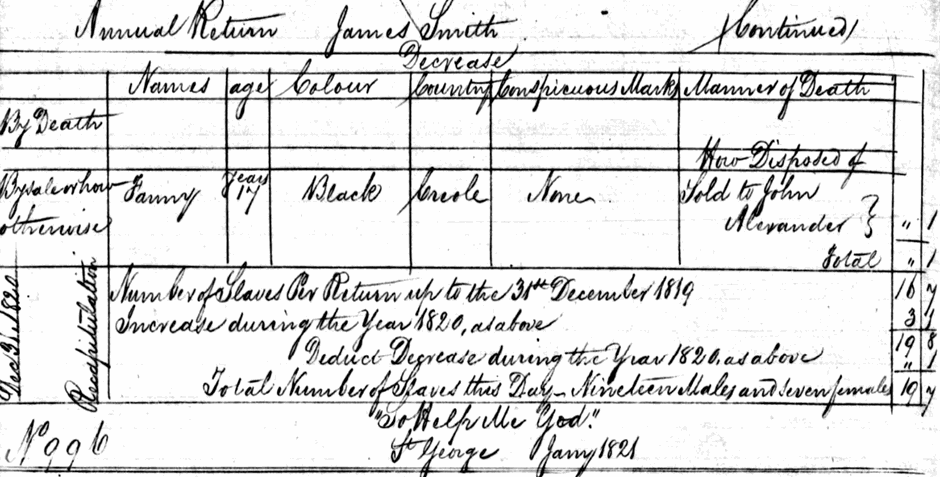

Fanny first appeared in the Slave Register of 1817. She was one of the 24 enslaved people at the Good Hope Estate, Petit Martinique (listed under St George in the Slave Register) under the control of James Smith. She was 14 at the time and born enslaved.

James sold her in isolation in 1820 to John Alexander. She was separated from the wider group with whom she had lived and worked. This isolated sale suggests no consideration was given to kinship, familiarity or stability. She was cut adrift from everyone she had grown up with.

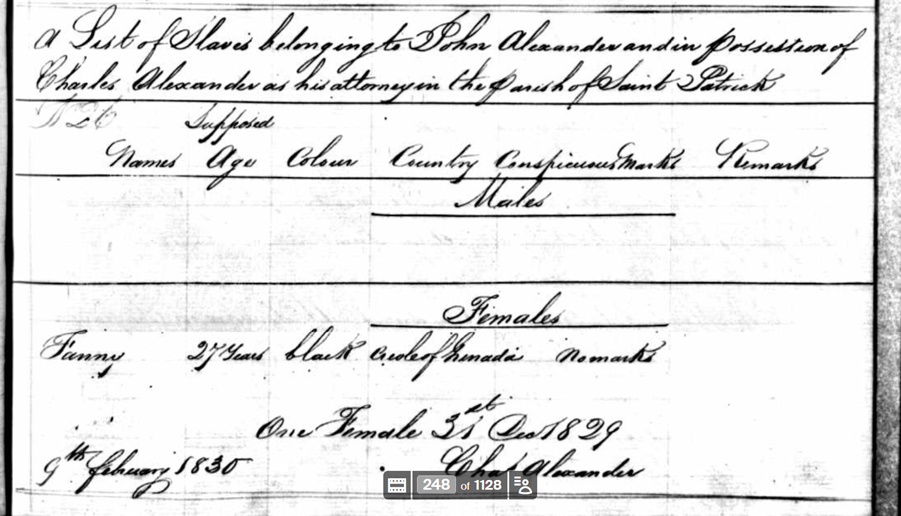

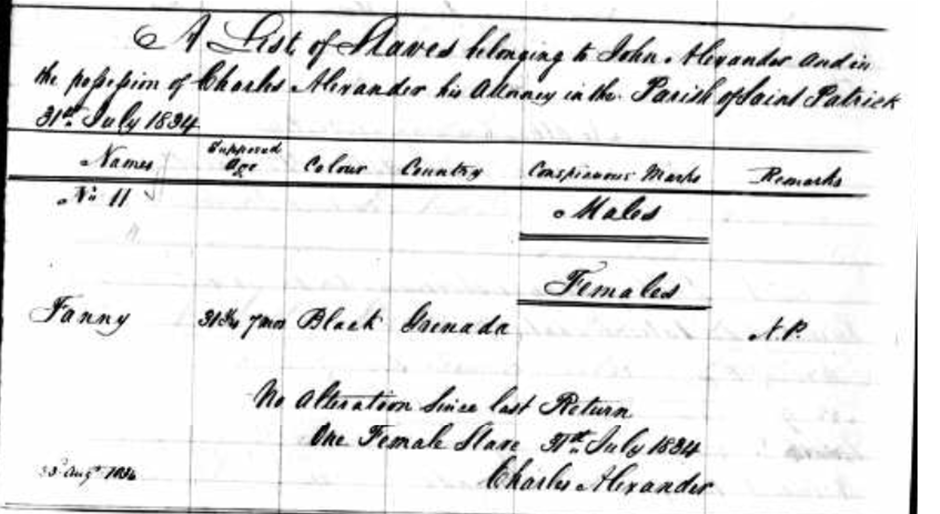

By 1829, Fanny had been moved once more, this time from St George to St Patrick. Although John Alexander remained the legal owner, day-to-day control passed to his brother, Charles Alexander, who acted as his attorney on the island. This shift, recorded formally in the slave registers, highlights how Fanny’s life was governed by decisions made by others, often for administrative convenience, with no reference to her wishes or wellbeing. Movement between parishes meant adapting again to new routines, terrain and expectations.

Fanny stayed in this setting right up to abolition where she would then have entered the apprenticeship scheme before her eventual release in 1838. She would have been about 35/36 years old at emancipation and could finally have some choice as to how to live the rest of her life. She was the one enslaved person that John Alexander claimed compensation for.

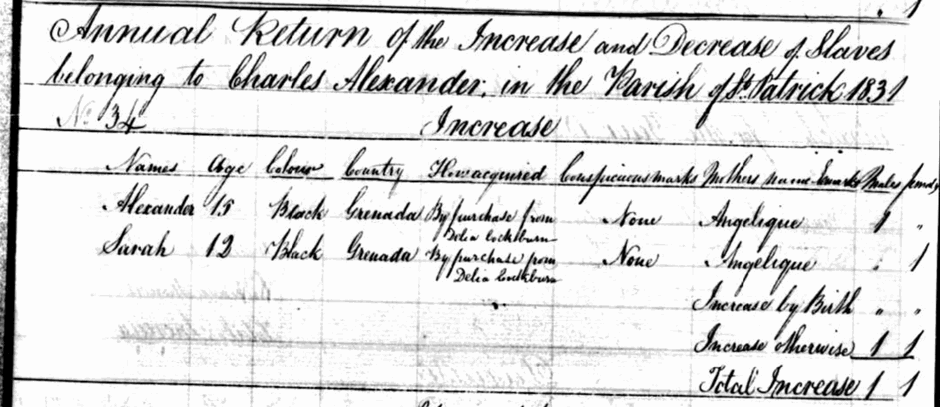

Alexander and Sarah

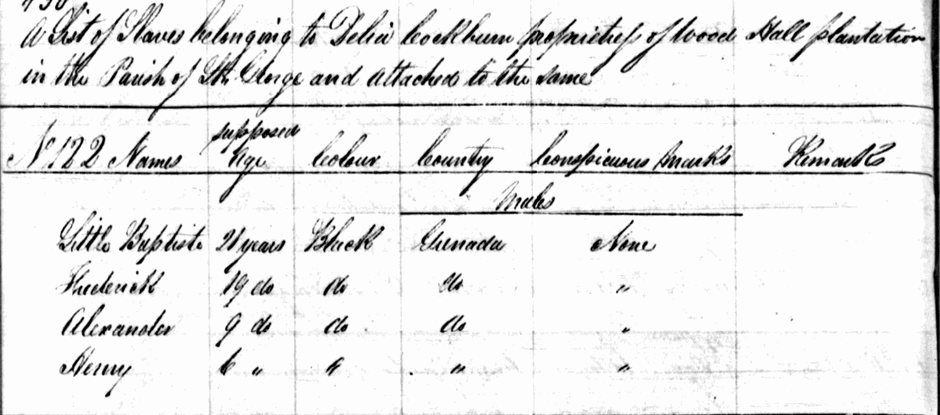

Sarah and Alexander were born enslaved on Woodhall Estate in St George, Grenada, into a family whose bonds were repeatedly broken by sale and transfer. Their earliest appearances in the colonial records already reveal how fragile family life was under slavery, even for very young children.

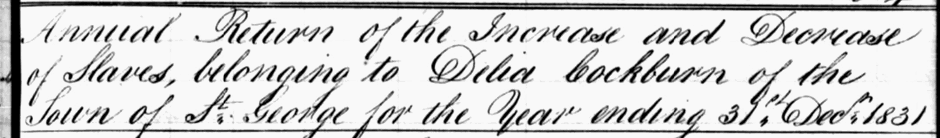

Sarah first appears in the 1821 Slave Register at just two years old, recorded under the control of Delia Cockburn, a free-coloured woman who herself occupied a complex position within Grenadian society. Delia had a daughter, Elizabeth Cockburn, with Alexander Cockburn, a Scottish man and son of Walter Cockburn. Elizabeth was later formally acknowledged in her father’s will. Despite Delia’s free status and her proximity to white Scottish networks, the people she enslaved remained subject to sale, separation and exploitation.

By 1825, the registers show that Alexander, aged nine, was also enslaved on Woodhall Estate under Delia’s control.

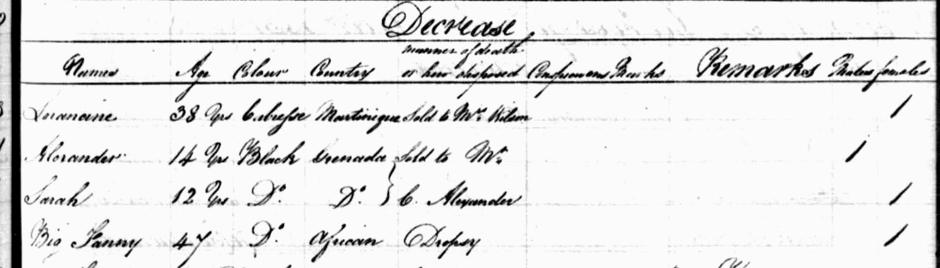

In 1831, when Sarah was about fourteen and Alexander around twelve, Delia Cockburn sold both children to Charles Alexander. This sale formally severed them from the people they grew up with at the Woodhall Estate.

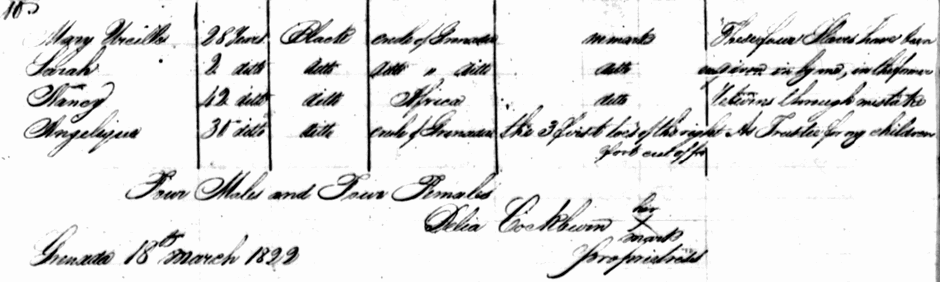

In Charles Annual Return, it is clear that Alexander and Sarah were indeed siblings. Their mother, Angelique, was herself born enslaved in Grenada in 1791. The earliest surviving register for Angelique dates from 1821, where she is described as having “the 3 first toes of the right foot cut off” which may have resulted from a work related accident from an agricultural tool. Angelique was, consequently, separated from her children and she remained with Delia right up to 1834.

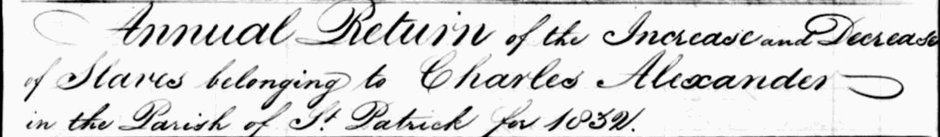

The family unit was broken again when Alexander was 16 in 1832 as Charles sold him to Robert Walker.

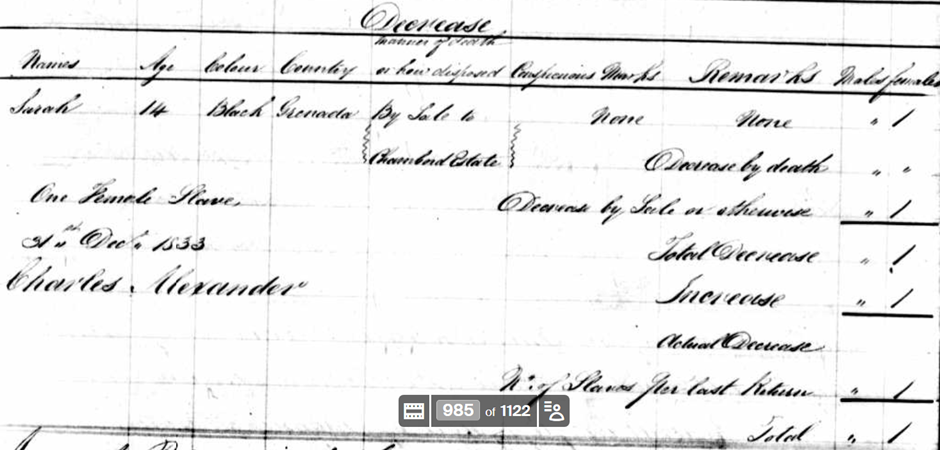

…and then Sarah was sold the following year to the Chambord Estate, compounding the family’s dispersal. By this point, Angelique had been separated from both children, and Sarah and Alexander were separated from each other, each forced into a different enslaving environment, routine, and future.

…and then Sarah was sold the following year to the Chambord Estate, compounding the family’s dispersal. By this point, Angelique had been separated from both children, and Sarah and Alexander were separated from each other, each forced into a different enslaving environment, routine, and future.

By the mid-1830s, the legal structure that had governed and fractured Angelique’s family for decades collapsed following abolition and emancipation. Although slavery formally ended in 1834, Angelique, Sarah and Alexander, like thousands of others, were forced into the apprenticeship system, a final attempt to preserve control over their labour. Yet the direction of travel had changed, and for the first time the future was no longer entirely dictated by sale and transfer.

For Angelique, born enslaved in 1791, survival itself was an act of endurance. She had lived through injury, separation and loss, yet remained alive into the final years of slavery. When emancipation arrived in 1838, she was in her late forties. This was an age at which many formerly enslaved women sought to rebuild family networks, form households of their own choosing, or remain within familiar communities where mutual support mattered more than ownership ever had. Even if she did not reunite physically with her children, emancipation removed the legal power that had once allowed others to sell her, punish her body, or define her existence as property.

For Alexander, sold away from his family at sixteen, freedom arrived at a pivotal moment. Emancipation meant that he entered adulthood no longer as a transferable asset, but as a man able, however constrained by poverty and racial hierarchy, to decide where to work, whom to associate with, and how to name himself. Many young men of his generation moved into skilled labour, maritime work, or small-scale agriculture. The right to remain with his family had been denied to him in childhood but this was replaced by the possibility of forming one of his own and perhaps reuniting with his sister and mother.

For Sarah, freedom came in her early twenties. Having endured repeated sales as a child and adolescent, emancipation offered something she had never known: stability that could not be undone by a signature or a ledger entry. Like many formerly enslaved women, she may have sought out family connections, chosen paid domestic work, cultivated provision grounds, or established an independent household. The choices available to her were limited, but they were hers in a way they had never been before.

What is most important is this: the system that broke Angelique’s family could no longer break it again. Whatever paths Sarah, Alexander and Angelique took after 1838, they did so as free people under the law. Their names ceased to appear in slave registers, sales columns and ownership returns, not because they vanished, but because the records that once reduced them to property lost their power.

In that silence of the archive lies a different kind of presence: the possibility that, after decades of enforced separation, labour and loss, Angelique, Sarah and Alexander finally lived lives shaped by survival, resilience and choice.

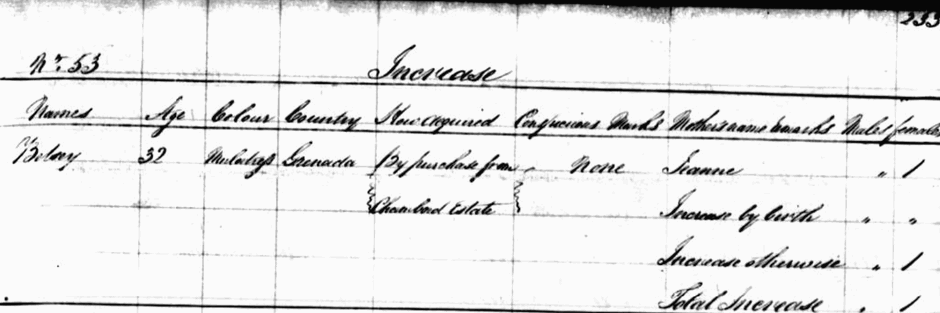

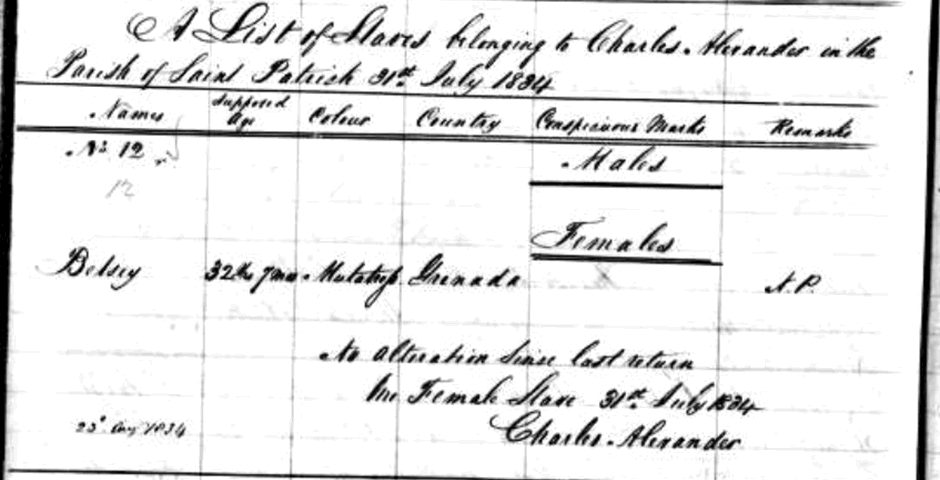

Betsey

As Sarah was being sold to the Chambord Estate, Charles Alexander bought Betsey, age 32, from the same estate that year (1933). Betsey was effectively separated from her mother Jeanne.

She first appeared in the 1817 slave Register under the control of Walter Cockburn with Owsley Rowley acting as his attorney (Walter likely to have been the same Walter Cockburn mentioned earlier and residing in Scotland). She was described as being a mulatto born in Grenada.

Betsey remained with Charles until slavery was abolished and likely stayed on through the apprenticeship and then emancipation. She was the one person that Charles claimed compensation for.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support.

References

The ALEXANDERS of INVERKEITHNY LOCHABER and CLAN DONALD©, Compiled by Robert Alexander, 1926, Updated by Michael Outram, starting 1984 https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~ocarroll/genealogy/alex.htm

William Alexander (judge) - Wikipedia www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/45714

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/10515

Delia Cockburn https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/10666