Fact File:

Fanny or Jane Aberdeen Barbara Aberdeen

Claim Number: 274 Claim Number: 269

Compensation: £103 4S 1D Compensation: £20 12S 10D

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 4 Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1

Parish: St. Andrew Parish: St. Patrick

Parliamentary Papers: p. 96 Parliamentary Papers: p. 96

Life dates: d.1840 Life dates: 1797-1867

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

The story starts with…

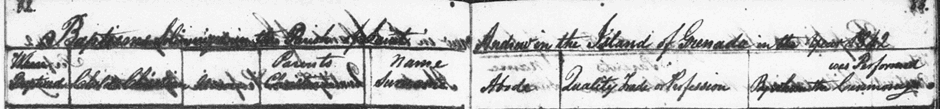

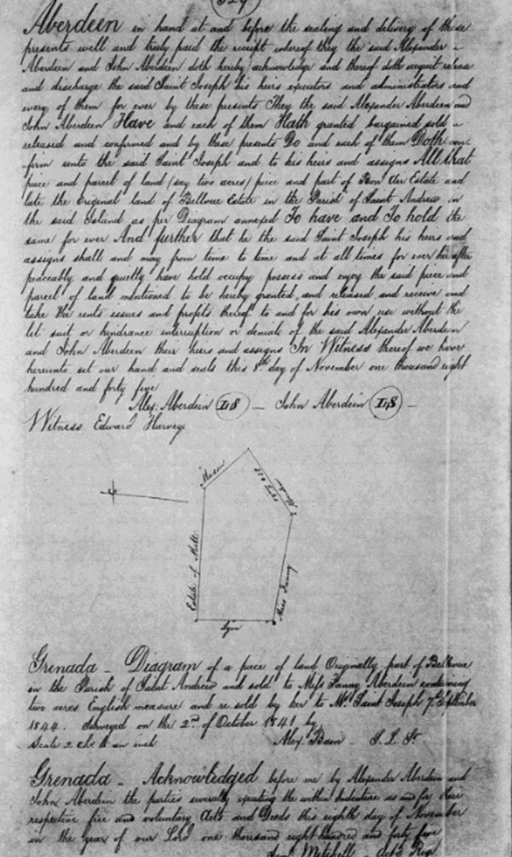

The Life of Alexander Aberdeen (1771–1815)

Alexander Aberdeen was born in Echt near Aberdeen, Scotland, where he was baptised on 23 May 1771. He was the son of Thomas Aberdein (1738–1815) and Grizel “Grace” Harvie (1735–1825). Both came from long-established Aberdeenshire families whose roots stretched deep into the rural north-east of Scotland. His father, Thomas, was the son of William Aberdein (1705–1779) and Jean Snowie (1711–1790) of Echt, while his mother descended from the Harvie/Mackay line through John Harvey (1691–1767) and Elizabeth Mackay (1691–1776). The extended Aberdeen, Murray, Snawie, Edward, Gordoun and Forbes lines form a rich network of Scottish farming and artisan families, many of whom lived for generations around Midmar, Echt, and Old Aberdeen.

This ancestry places Alexander firmly within the eighteenth-century Scottish demographic that fed heavily into British colonial expansion. Young Scottish men often the sons of farmers, blacksmiths and craftsmen frequently travelled to Grenada and other islands in the Caribbean seeking opportunity as clerks, book-keepers, overseers, and small planters. Alexander followed this path sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, joining a diaspora that would profoundly shape the social and economic world of the Grenada.

By the early 1800s, he had established himself as a planter in the parish of St Andrew, Grenada, with livestock, household goods and modest landholdings. He was literate, respected, and financially stable, moving within the circles of colonial administration and trade. Yet his personal life diverged in ways that reveal a complex and intimate connection to the people of Grenada.

In 1806, Alexander made a bold and unusual decision: he formally manumitted his “mulatto slave named Fanny”, freeing not only her but “all her future issue and increase.” Such language leaves little doubt that Fanny was his partner and that he intended to secure the legal and personal freedom of their children. This manumission placed Fanny and her existing or future children among the earliest free coloured families in Grenada nearly three decades before universal emancipation.

TRANSCRIPTION

Grenada Entered 21st October 1806

Know all Men by these Presents that I Alexander Aberdeen of the Island aforesaid, Esquire, for divers good Causes and Considerations me hereunto moving have manumitted enfranchised made free and from all ties of servitude absolved. And by these Presents do for myself my Heirs Executors and Administrators each and every of them manumit enfranchise and make free and from every tie of servitude absolve my mulatto Slave named Fanny and also all her future Issue and Increase, so that neither the said Alexander Aberdeen nor my Heirs Executors or Administrators or any or either of them shall from henceforth have claim challenge or demand any Right or Title by reason of any slavery or villainage in the said Fanny or her future Issue but that the said Fanny and her future Issue shall from henceforth for ever hereafter be as free to all Intents and Purposes whatsoever as any other Subject of His Majesty King George the Third.

His will, written in 1815, confirms the depth of this relationship. In it, Alexander left everything, after settling debts to Fanny and her children: Jenny, Alexander, Grace, John, Agnes, Eliza and Thomas Hillington. He further acknowledged another daughter, Barbara Aberdeen, who he described as a free mulatto. This open recognition of a mixed-heritage family was unusual among Scottish planters of his time, many of whom fathered children from enslaved or formerly enslaved women but did not legally provide for them. Alexander’s choices ensured that his children would inherit property, security, and social legitimacy uncommon for people of mixed ancestry in the early nineteenth century.

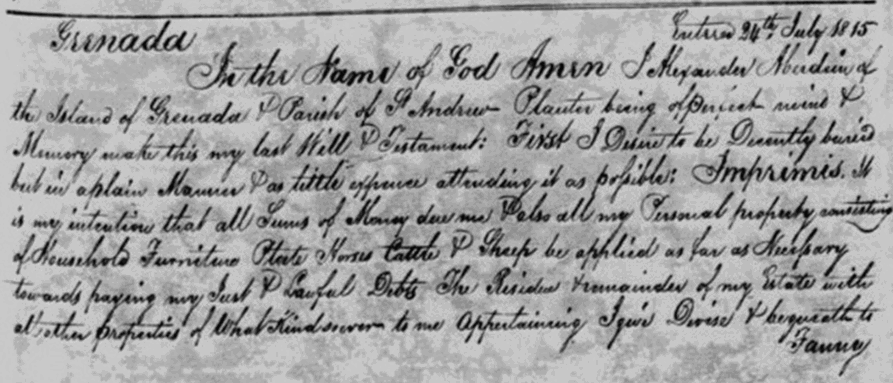

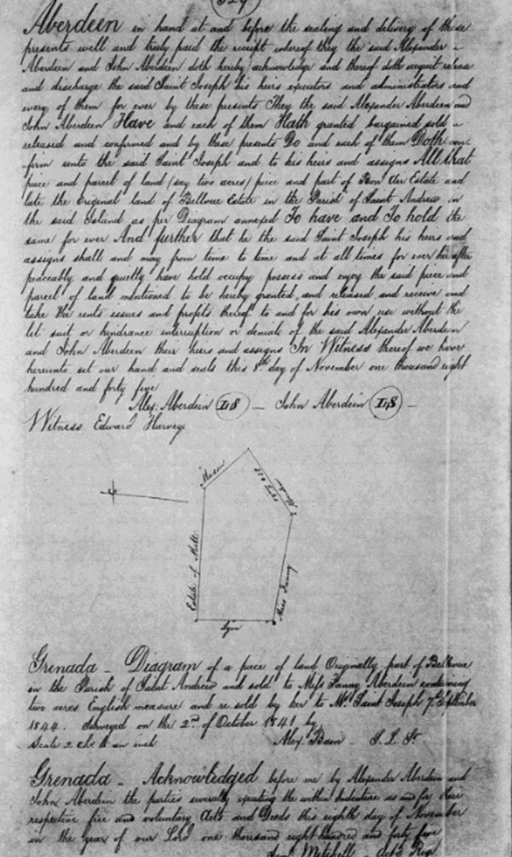

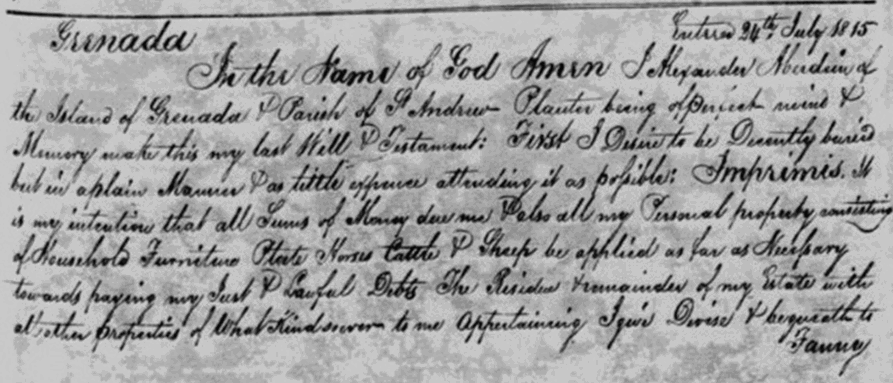

TRANSCRIPTION

Grenada Entered 29th July 1815

In the Name of God Amen I, Alexander Aberdeen of the Island of Grenada, Parish of St Andrew, Planter, being of sound mind & Memory make this my last Will & Testament. First I Desire to be Decently buried but in a plain Manner & as little expense attending as is possible. Imprimis it is my intention that all Sums of Money due unto Me & also all my Personal property consisting of Household & Furniture Plate Horses Cattle & Sheep be applied as far as Necessary towards paying my Just & Lawful Debts. The residue & remainder of my Estate with all other properties & What Else is or may be Appertaining I give Devise & Bequeath to Fanny Aberdeen a Woman of Colour & her Children or their Survivors, viz. namely as follows, Jenny, Alexander, Grace, John, Agnes, Eliza and Thomas Hillington, & likewise any money there is to be applied towards their Maintenance & bringing of them up to be paid out of Interest for their benefit. Lastly, I Constitute & Appoint George Paterson, practitioner of Physic, Robert Kennedy, Alexander Rofs doctor of medicine and Joseph Simpson Esquire all of the Island of Grenada executors of this my Last Will and Testament and I do request all parties of the named executors to accept individually the sum of fifteen pounds sterling money as a mark of respect for them. This I declare to be my Last Wills & Testament. In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand & Seal this fifteenth

day of June in the Year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred & Fifteen.

Signed, Sealed & Declared by the within:

Alexander Aberdeen (LS) to be his Last Will and Testament in presence of us who subscribed our names in prescence of said testator and each other

David Patterson King

Yves Delatouche

Angus Campbell

Lastly, I further request and wish that my reputed Daughter Barbara a free mulatto girl

be paid an equal share of the Residue & Remainder of my property with the aforesaid seven children.

In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand this fifteenth day of June 1815

in presence of the above witnesses; the Codicil was signed in the presence of us whose names are herunto subscribed.

David Patterson King

Yves Delatouche

Angus Campbell

By making these provisions, Alexander ensured that his family formed part of Grenada’s emerging free coloured class that later became significant in Grenada’s social and political landscape.

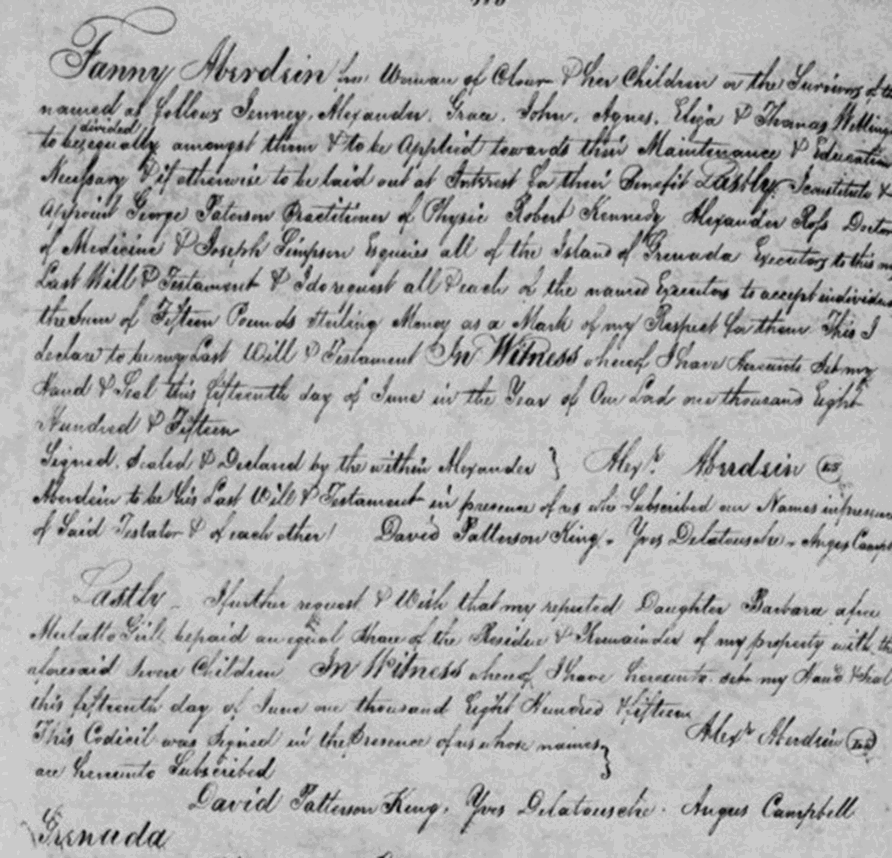

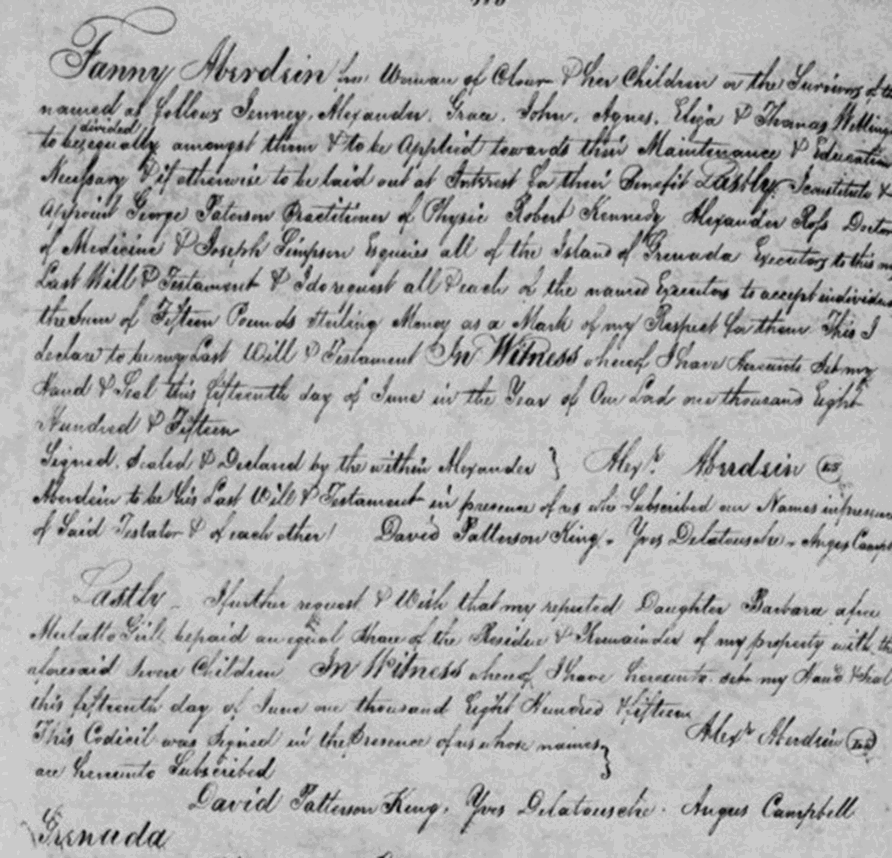

His death was reported in the St Georges Chronicle and Grenada Gazette on July 5 1815.

The Life of Fanny (or Jane) Aberdeen (-1840)

Fanny Aberdeen, sometimes also recorded as Jane Aberdeen, was manumitted by Alexander Aberdeen in 1806 and named in his will with her children as a free woman of colour. Her children took his name and there is little doubt that Alexander was their father.

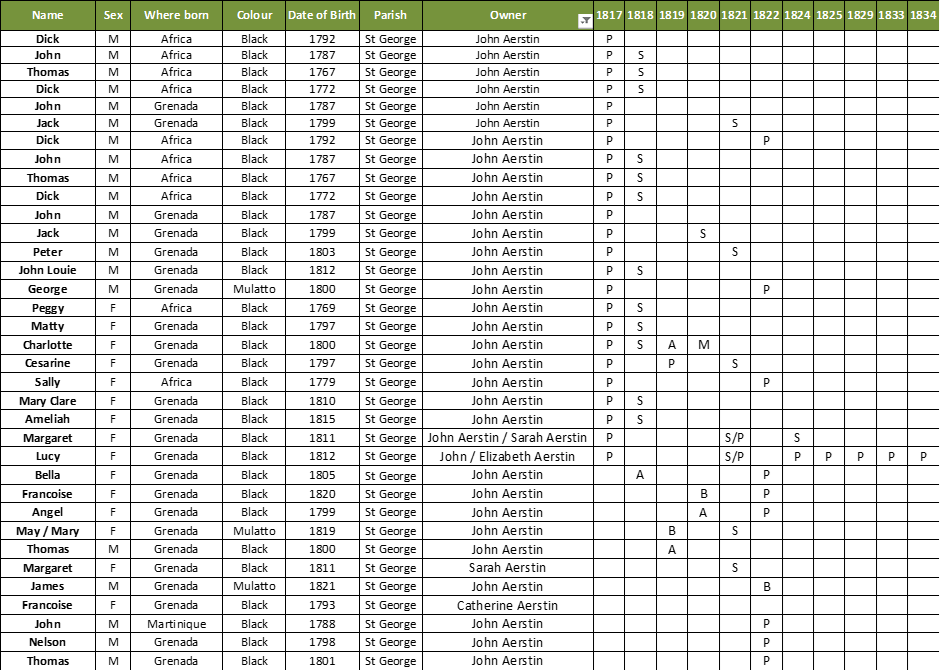

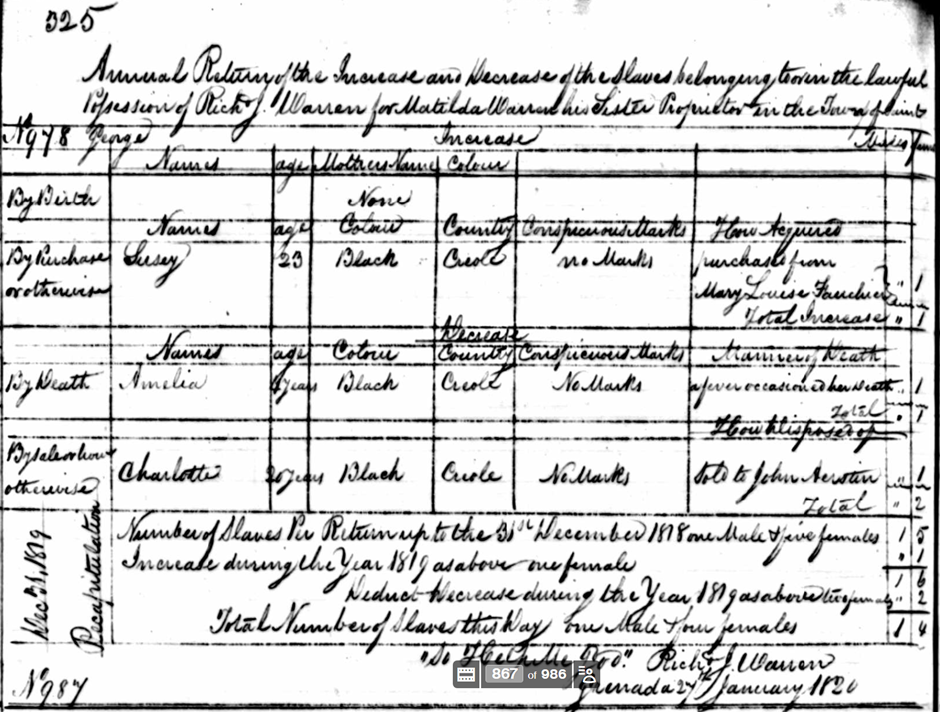

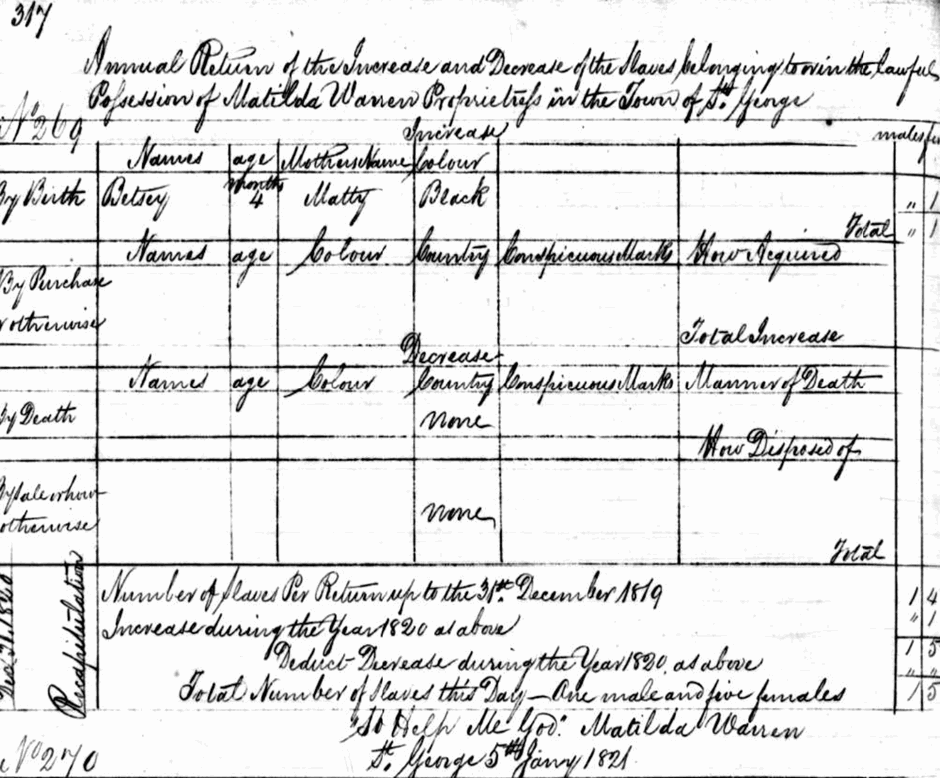

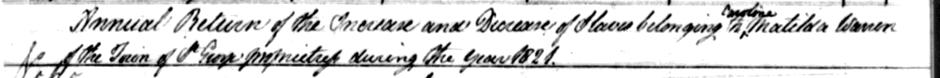

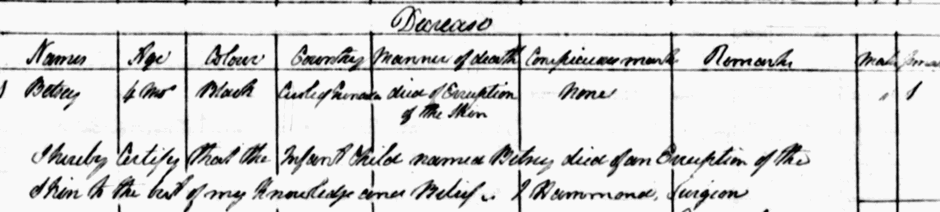

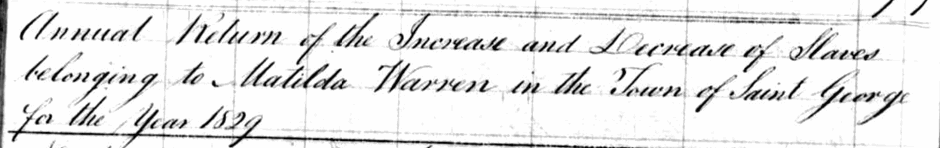

Fanny’s life was deeply woven into the machinery of enslavement in early 19th-century Grenada. Over nearly two decades she appears consistently in the Slave Registers of St Andrew, buying, selling, managing, and reporting on the lives of the people she enslaved. Her long paper trail shows that she was an active participant in the system, acquiring people through purchase and Marshal’s sale, selling them on again, and acting as trustee for other proprietors.

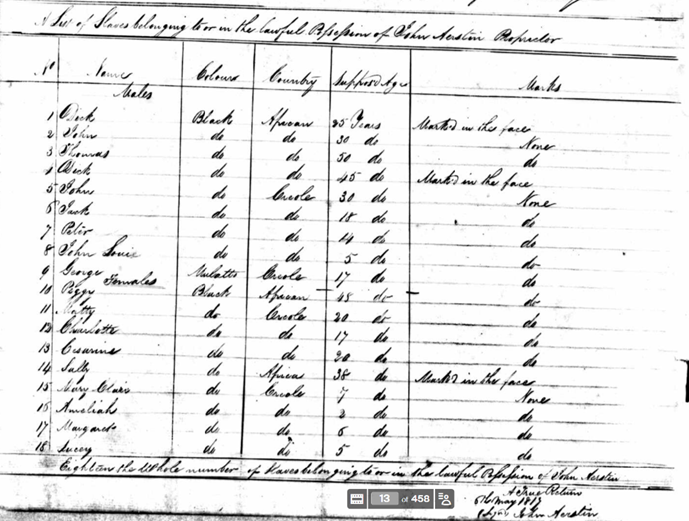

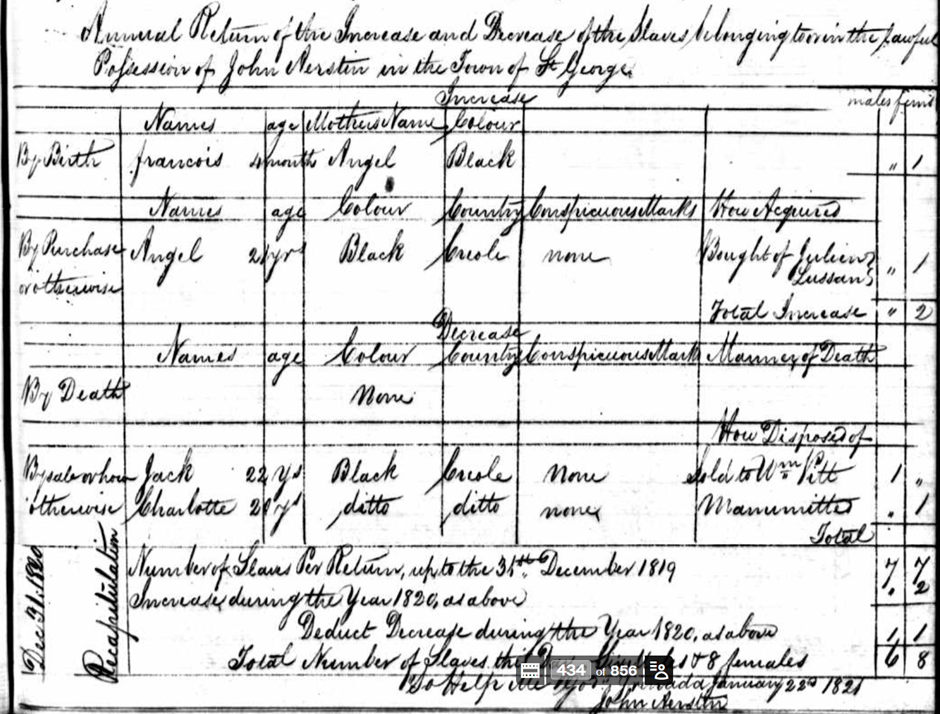

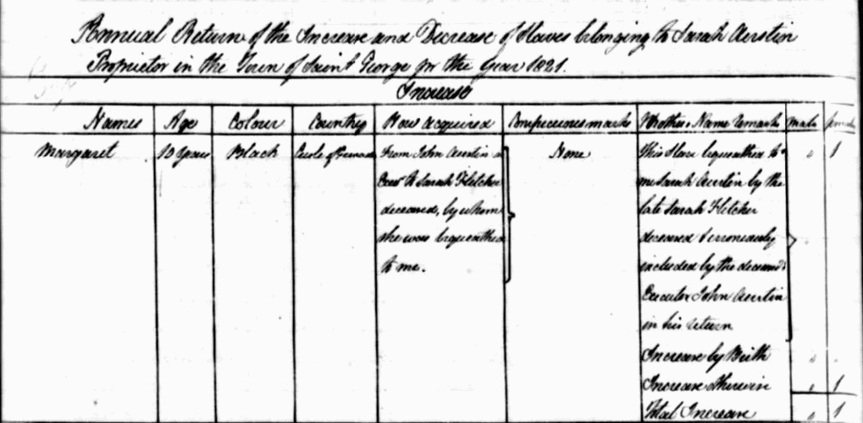

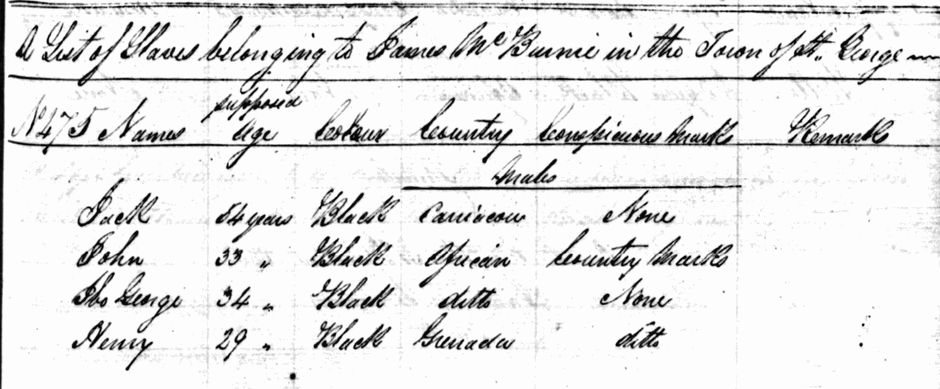

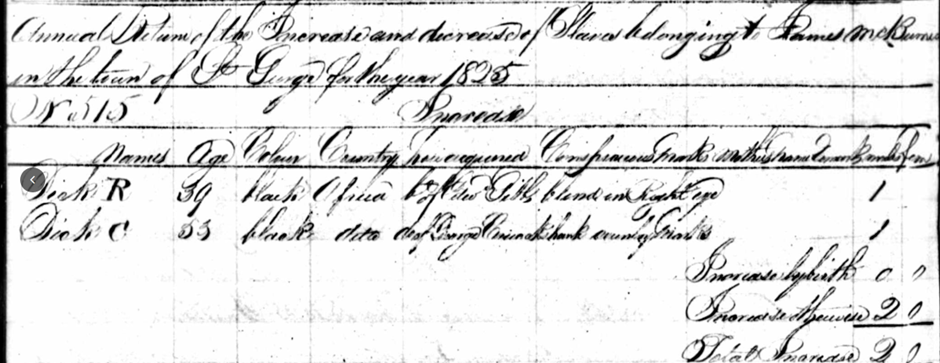

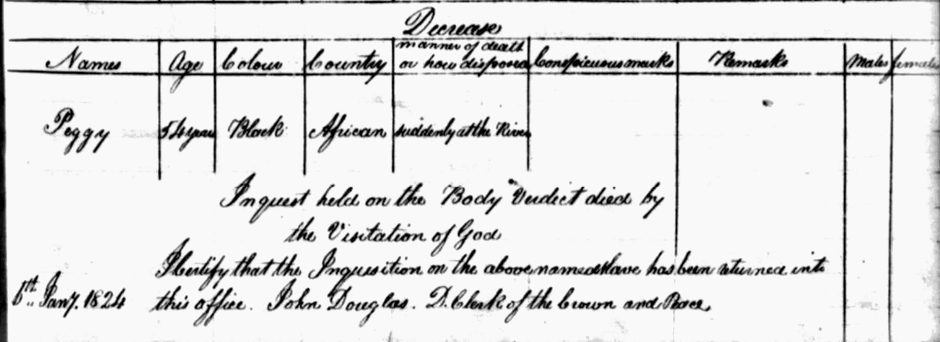

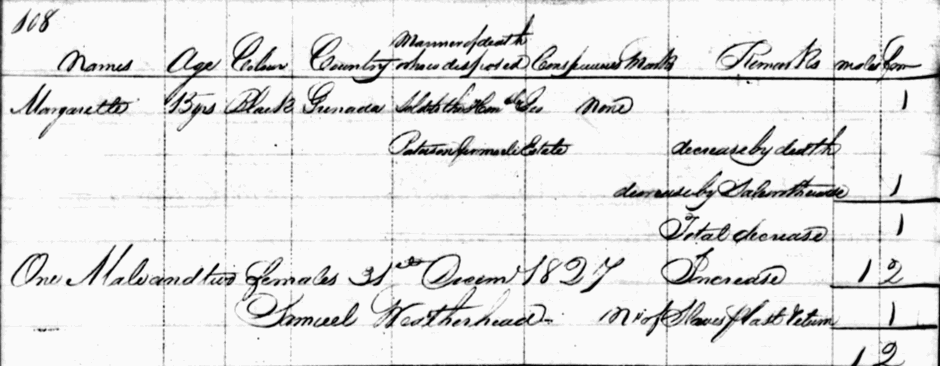

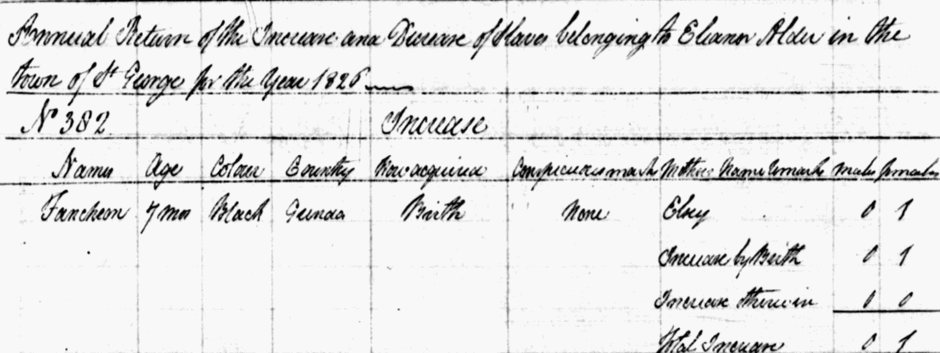

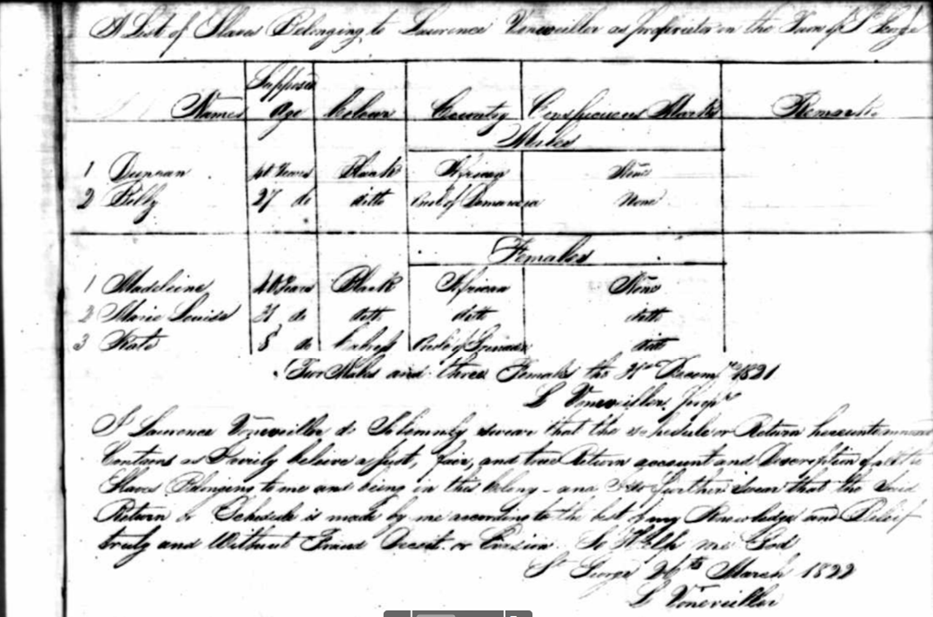

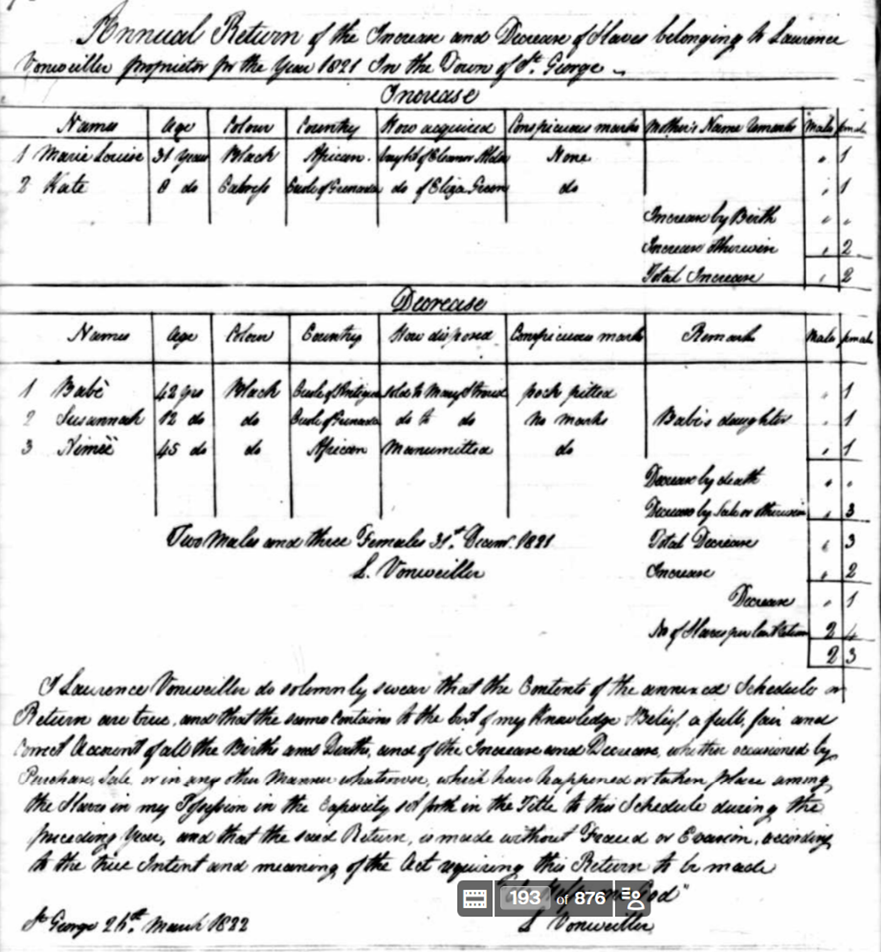

Early Years in the Registers: 1817–1821

Fanny first appears in the 1817 Slave Register with eight enslaved people: six African-born adults: Sandy, Neilson, Nancy, Lidia, Charlotte and Louisa (all in their 30s and 40s), and two five-year-old children, Billy and Alicia, who were born enslaved in Grenada. Her reporting of Louisa’s death in 1819 reveals the harsh conditions they endured: Louisa died at 42 of “mal d’estomac,” a term used on Caribbean plantations for the fatal consequences of pica, the desperate practice of dirt-eating that enslaved Africans used as an act of bodily resistance or to cope with trauma.

By 1821, Fanny was already participating in the slave market, selling Sandy, who had ben with her since at least 1817, to John Chapman. Despite confusion in the archival indexing, she was operating in St Andrew, Grenada and not Jamaica as stated incorrectly in the record.

Expansion and High Turnover: 1822–1825

From 1822 onwards, Fanny’s involvement intensified. She bought six more people from Julien Allan Delatouche, four of them African-born, and two, Bonette and Jean Rose, born in Grenada. Bonette was described as a mulatto girl of about eleven. Children of African and European descent were often highly valued for domestic labour.

That same year she reported the deaths of Billy (age 9) and Charlotte (age 37), both from mal d’estomac, an indicator of profound distress among the enslaved. Still, acquisitions continued. The following year she sold Bella and Julie back to the Delatouche family and reported Nancy’s death, again from mal d’estomac.

In 1823, Fanny made further purchases. John, Rosette and little Frances while also signing as trustee for enslaved people owned by Sophia, Caroline and John Alexander. Her dual signature, sometimes as Jane, sometimes as Fanny, appears consistently across the records, confirming that both names referred to the same woman.

In 1825 was still active: she reported the birth of another child, also named Frances, giving her a workforce of two men and seven women. She was simultaneously managing a second place, in her name Jane Aberdeen, where Rosette gave birth to Margaret. At this point she controlled enslaved people either directly or as trustee at three separate places.

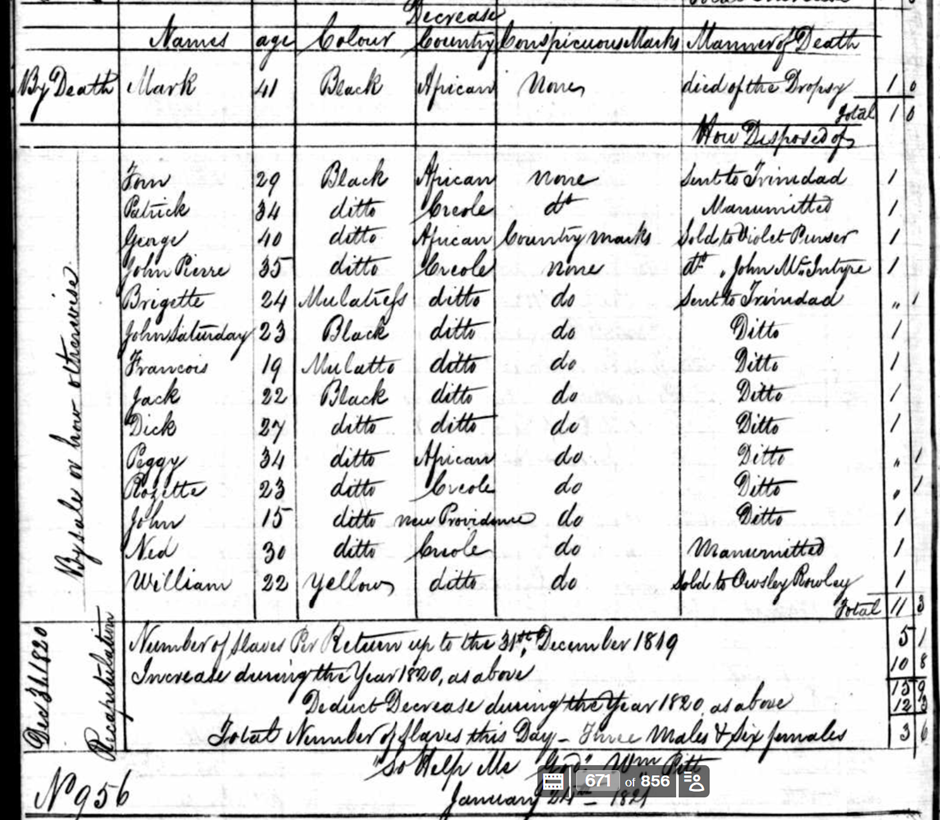

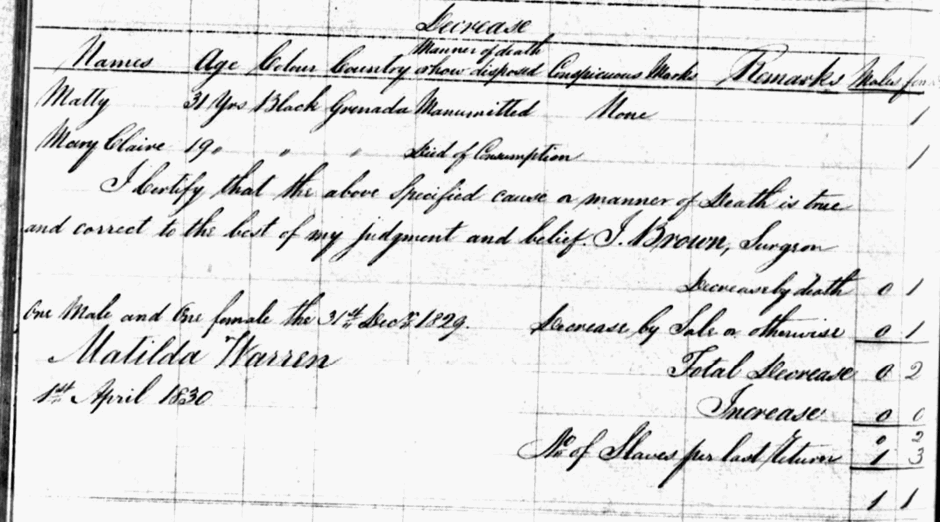

Decline and Consolidation: 1826–1830

The later 1820s show a pattern of reduction, sale, manumission, and re-adjustment. Lydia died in 1826. Several others; Breeche, Jean Rose and Renette (Bonette) were sold back to Delatouche. Lease and her child Eliza were sold in 1828; Susannah was manumitted that same year, and by 1829 Fanny had only two enslaved people left: Nelson and Alicia, who had been with her since childhood.

But in 1830, she suddenly expanded again acquiring Fanny (23), Charles (7), David James (19 months) and baby George from a Marshal’s sale. These four were described as mulattoes and had been brought together as a family group. For a short time, h er workforce rose to six.

er workforce rose to six.

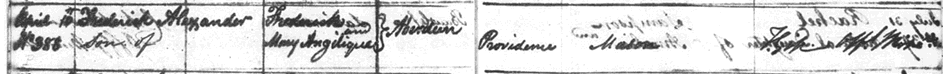

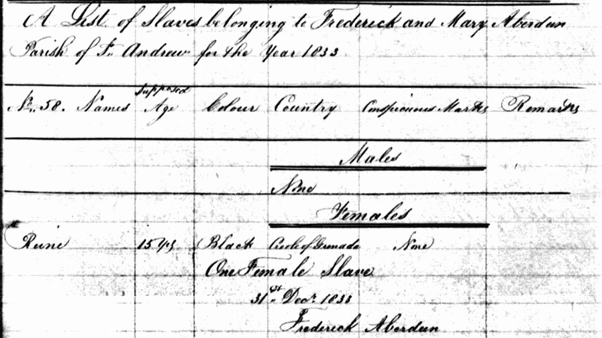

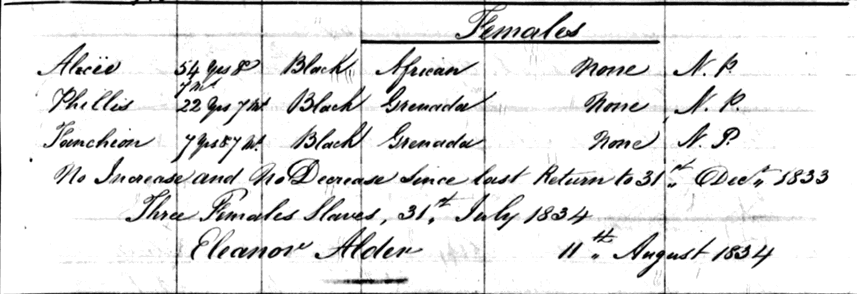

Final Years of Enslavement: 1831–1834

Her newly purchased teenager Felisha died at sixteen in 1831, once again from mal d’estomac. The following year Fanny sold the entire mulatto family group to Catherine Drysdale, reducing her holding to a single enslaved man.

In 1833, Fanny’s affairs were administered not by her directly but by her son, John Aberdeen, acting as her agent, suggesting she was unable to appear in person. Nelson, then around 40, was the last person she held.

In 1834, Matthew Lumsden acted as her agent and reported Nelson’s death yet again attributed to mal d’estomac. With his death, the group of enslaved people directly under Fanny’s control came to an end.

Compensation and Death

On 12 October 1835, Jane Aberdeen filed a claim for compensation for four formerly enslaved people. These were likely the individuals she managed as trustee on behalf of the Alexanders rather than her own. The compensation records confirm her continued involvement in the institution even after emancipation.

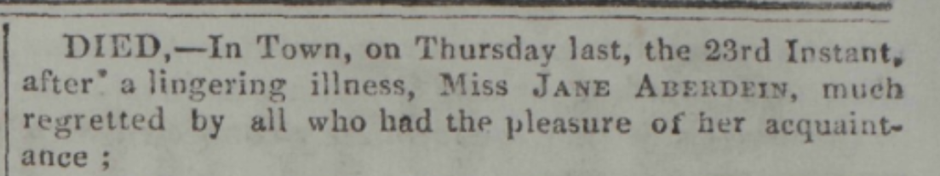

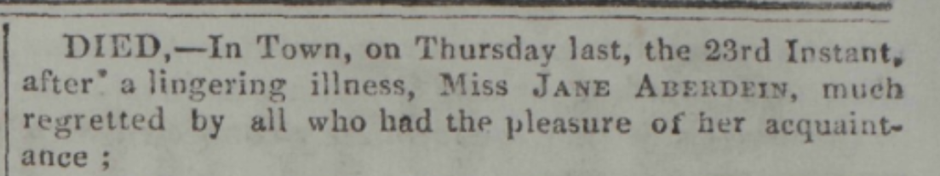

Jane “Fanny” Aberdeen died on 23 September 1840, with a death notice published in the St George’s Chronicle on 3 October that year closing the life of a woman whose personal history mirrors the evolution, harsh nature and persistence of slavery in Grenada.

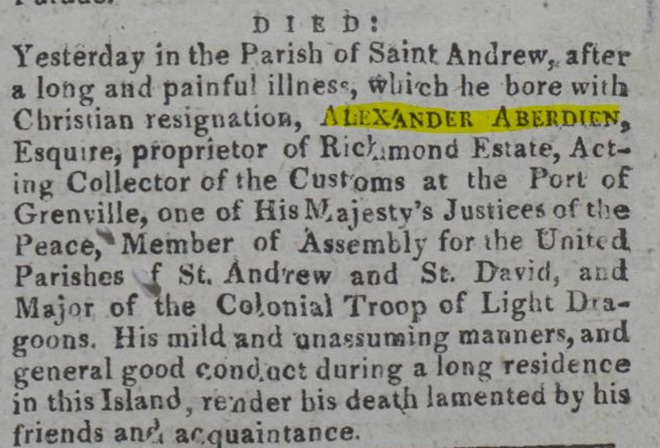

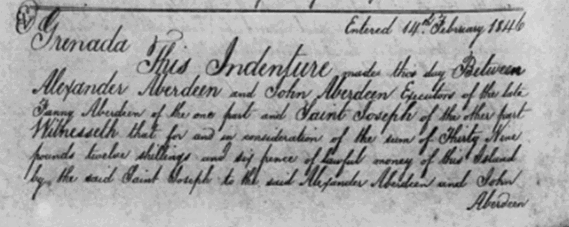

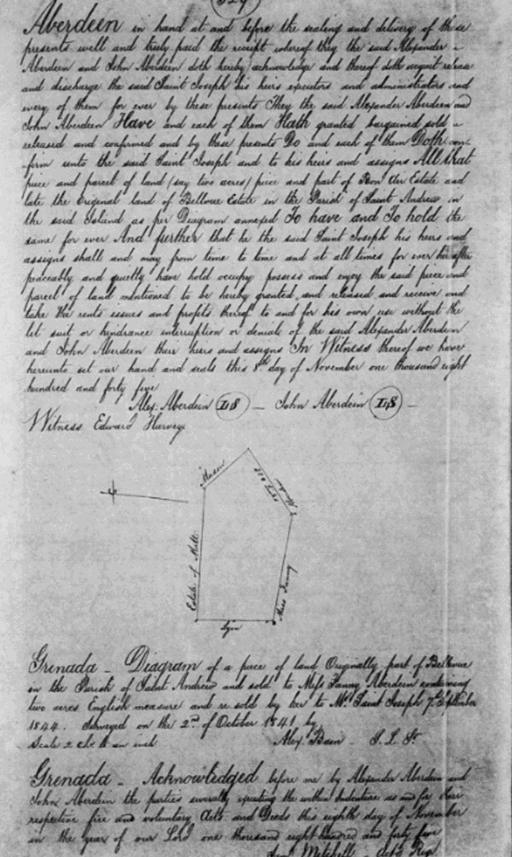

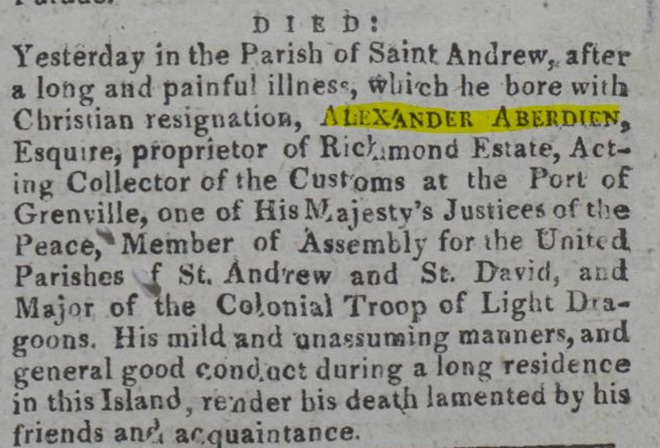

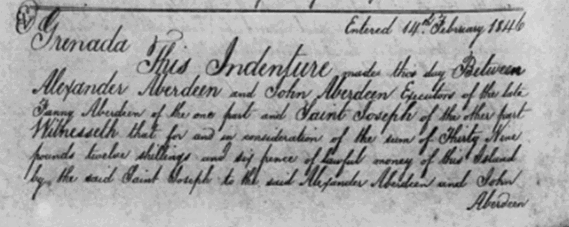

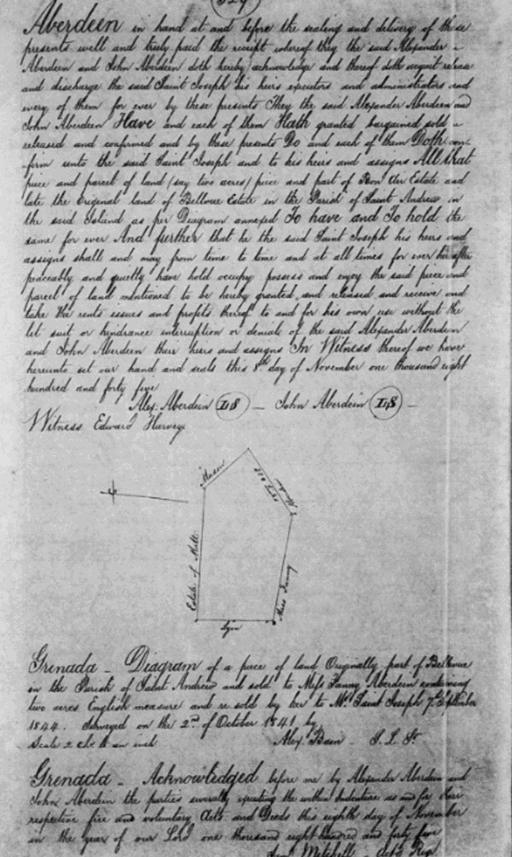

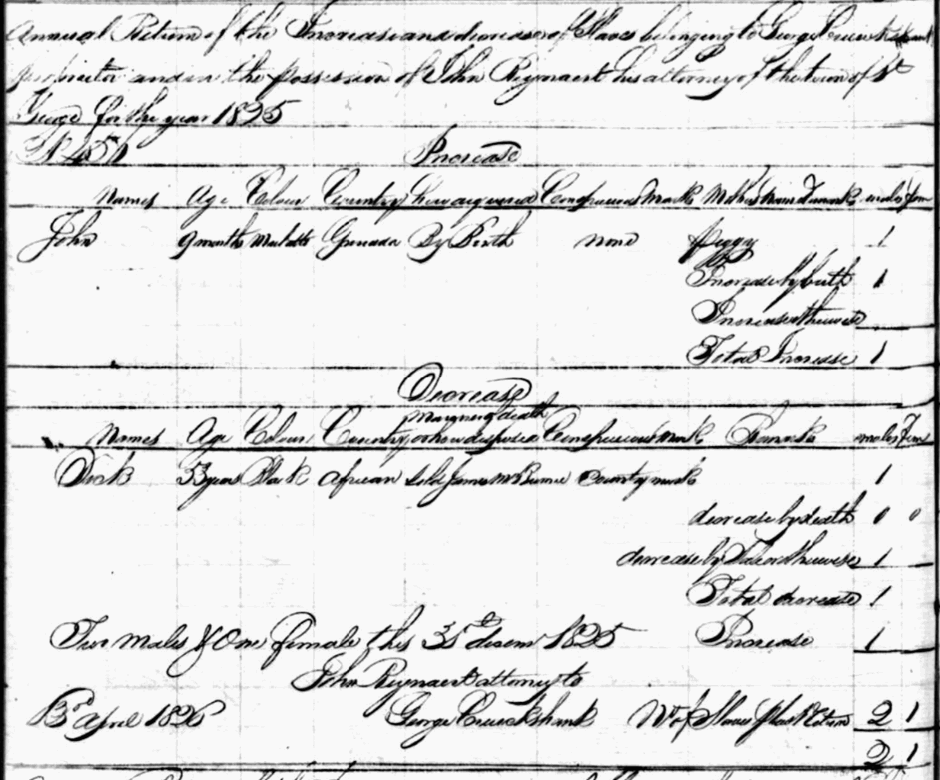

1846 Indenture

The indenture documents the sale and transfer of land in St Andrew, by John and Alexander Aberdeen acting as executors of the late Fanny Aberdeen. They are most likely her sons and it was John Aberdeen that handled her slave register in 1933. They acknowledge receiving the sum of thirty-nine pounds, twelve shillings and six pence from a man named Saint Joseph. This payment completed the sale of land formerly belonging to Fanny Aberdeen, forming part of the settlement of her estate after her death.

It refers to forty-two acres, originally part of the Bellona Estate in the St. Andrew. A survey diagram was included in the original document. The indenture formally grants, sells, releases and confirms the land to Saint Joseph and guarantees that he and his heirs may hold, occupy and enjoy it permanently without interruption or dispute. The document is signed and sealed by Alexander and John Aberdeen and witnessed by Edward Harvey.

Alexander Aberdeen’s children

Of his children we note the following:

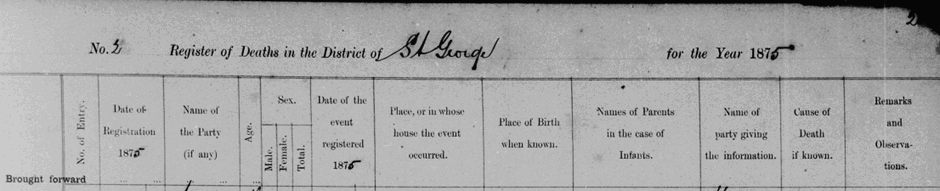

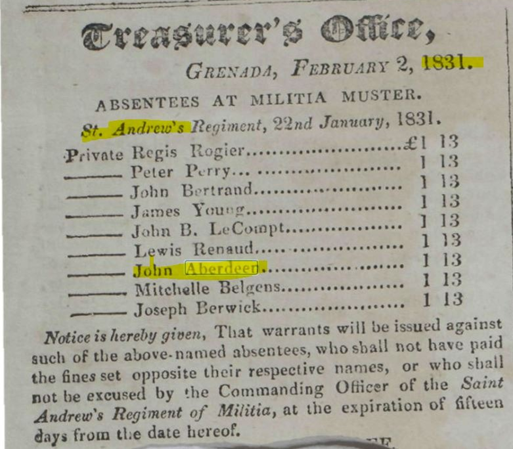

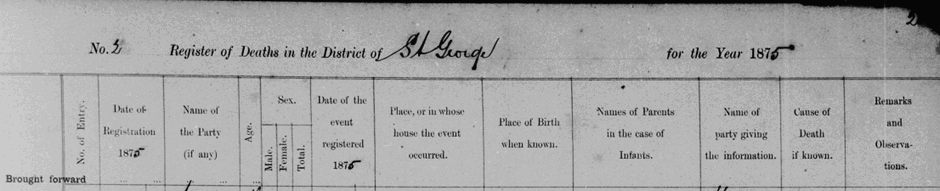

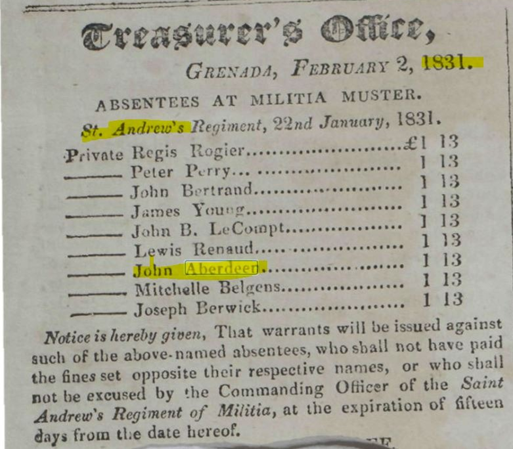

The Life of Alexander Aberdeen (Junior) c1801-1875

Alexander Aberdeen Junior was one of the most prominent members of Grenada’s free coloured community in the nineteenth century. Born in St Andrew in the first years of the 1800s, he was the son of Alexander Aberdeen, a Scottish-born planter from Echt, Aberdeenshire, and Fanny, a mixed-heritage woman whom his father had enslaved but later freed.

In 1806, when Alexander Junior was still very young, his father executed a formal deed of manumission freeing Fanny and “all her future issue,” which meant that Alexander Junior was legally free decades before the emancipation of enslaved people in the British colonies. When his father died in 1815, he named Fanny and all their children as his heirs. Alexander Junior therefore grew up in the rare position of being a free, property-connected person of colour in early nineteenth-century Grenada, at a time when such status provided crucial stability and opportunity.

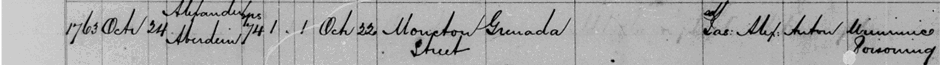

As he reached adulthood, Alexander Aberdeen Junior established himself in St George’s and began his working life as a book-keeper in several commercial firms.

This occupation was typical for free coloured and mixed-heritage men whose literacy and numeracy allowed them to move into clerical work rather than the manual labour expected of the enslaved.

Over time he gained the confidence of the colonial administration and was appointed Clerk of the Market in St George’s, a post that required daily supervision of trading practices, prices, weights and measures.

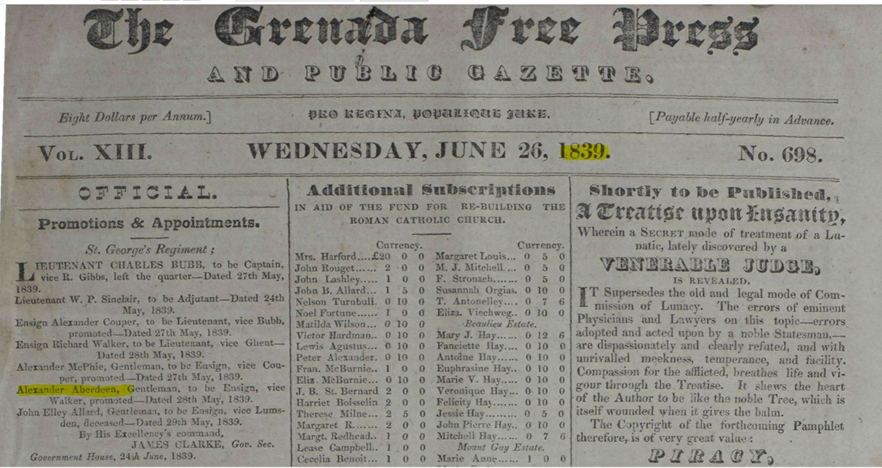

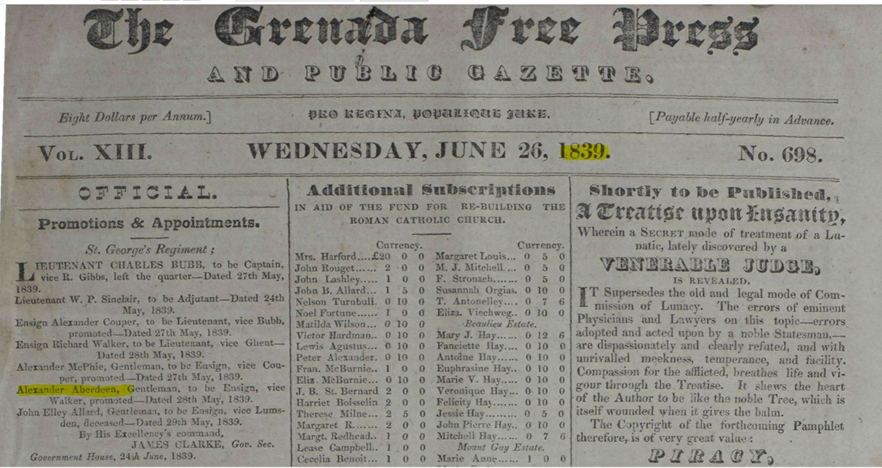

By the late 1830s Alexander Junior was sufficiently recognised to appear in official notices, such as the 1839 issue of The Grenada Free Press, which lists an “Alexander Aberdeen, Gentleman” as appointed to the post of Ensign in the St George’s Regiment. This was a commissioned junior officer rank. Although militia appointments often carried local political weight rather than military significance, they nonetheless signalled standing, respectability and acceptance among Grenada’s middle class.

Alexander Aberdeen Junior established himself as a literate and respected free coloured man within Grenada. He had grown up with a status that was unusual for someone of mixed descent in the early nineteenth century, having been freed along with his mother Fanny by his father in 1806. His later life demonstrates that he was relied upon for administrative and clerical responsibilities.

After his mother died, he was responsible for finalising the legal transfer of her property together with his brother John Aberdeen as executors of an indenture made on 11 February 1846. He was involved in ensuring that the land previously belonging to the deceased Fanny Aberdeen, could be lawfully conveyed to the purchaser, Saint Joseph. His participation indicates that he occupied a recognised position within family and local networks, responsible for executing legal formalities and safeguarding the proper transfer of title. His presence in this indenture is consistent with the reputation later described in his obituary of 1875, in which he is remembered as dependable, honest, and trusted in public matters.

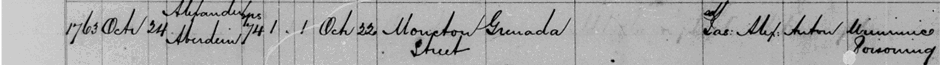

Alexander Aberdeen Junior lived a long life, reaching the age of seventy-four. He died on 3 October 1875 at his residence at Monckton Street, St George’s, after what the obituary described as a short illness although his death record indicates some sort of poisoning.

His obituary records that he later served as Treasurer of the Society for the Education of the Poor, an important charitable institution. His roles placed him squarely within the civic life of the town and testify to the trust placed in him by both the government and the community. He was also remembered as “honest, industrious and good-hearted,” a man agreeable in temper and respected for his “sterling qualities.” He appears to have been well known, with a large number of friends and relatives present at his funeral in the burial ground at Hospital Hill.

Alexander Aberdeen Junior’s life reflects a remarkable generational transition. His father’s decision to free Fanny and her children enabled Alexander to grow up as a free man, secure property rights, and participate in the civic and administrative life of Grenada in ways that would otherwise have been extremely difficult for a person of mixed heritage in the early 1800s. His long service, good reputation and prominent obituary show that he became a respected member of Grenadian society whose life bridged the eras of slavery, emancipation and early post-emancipation governance.

The Life of John Aberdeen

John Aberdeen belonged to the second generation of the Aberdeen family established in Grenada by the Scottish planter Alexander Aberdeen and the formerly enslaved woman Fanny, whom Alexander freed in 1806. He was named in his father’s will of 1815.

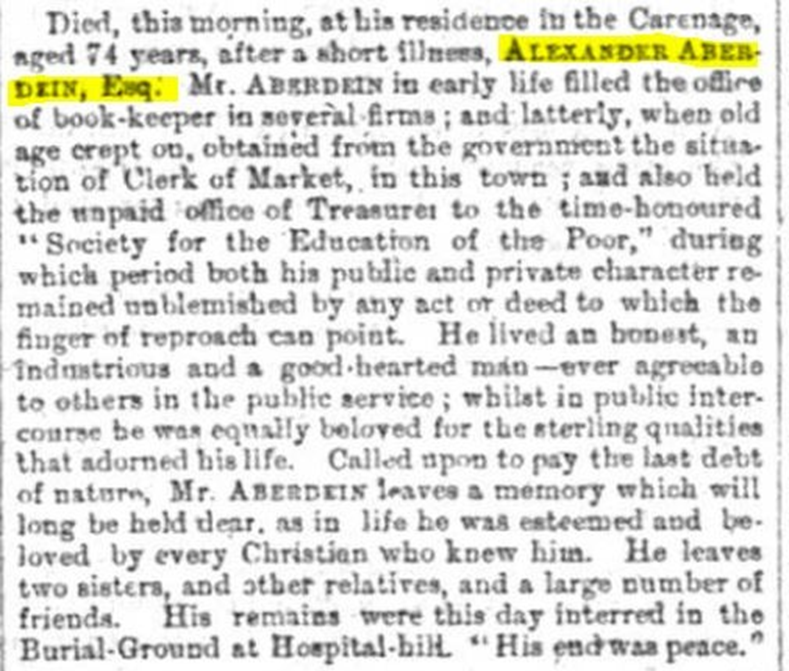

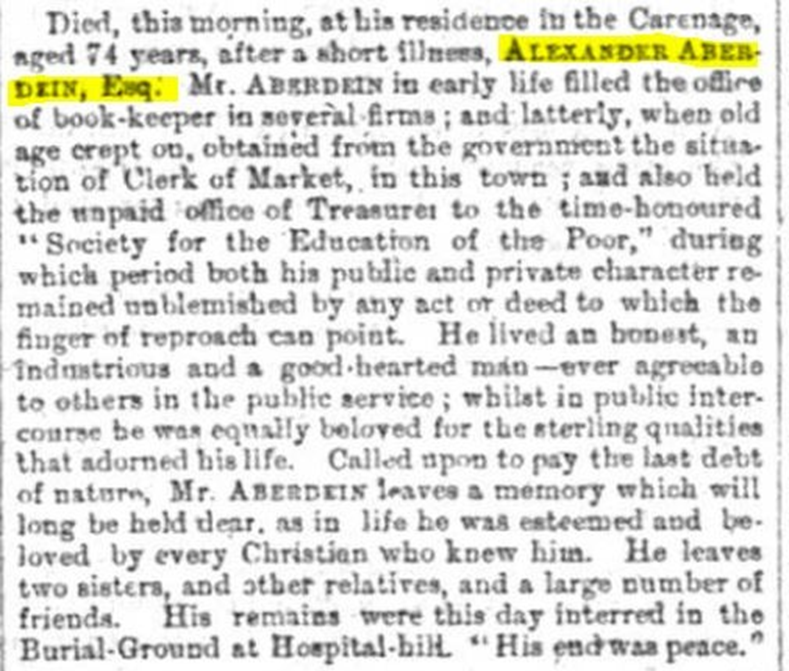

The earliest known reference to John Aberdeen appears in the Grenada Free Press of 2 February 1831. He is listed under the St Andrew’s Regiment of Militia as an absentee from muster. It should be noted that militia rolls were poorly attended across the Caribbean, and absences were frequent. Names appeared repeatedly in these lists without any consequence to a man’s social status, employment prospects, or respectability.

This notice places John squarely within the class of free coloured or mixed-heritage men who, by the 1830s, were required, or socially expected, to serve in local defence forces. His presence on the roll indicates he was officially recognised as a free man and a resident of some standing in St Andrew, since militia rolls did not typically include the poor or transient.

In the 1846 indenture relating to Fanny Aberdeen’s property, he appears as one of the executors of her estate, together with his brother Alexander Aberdeen. Being named as an executor indicates that John was trusted, literate, and capable of handling legal responsibilities. It also shows that by the mid-nineteenth century he was considered an adult of maturity and authority, involved in managing family property and representing the interests of the Aberdeens in official matters.

In the 1846 indenture relating to Fanny Aberdeen’s property, he appears as one of the executors of her estate, together with his brother Alexander Aberdeen. Being named as an executor indicates that John was trusted, literate, and capable of handling legal responsibilities. It also shows that by the mid-nineteenth century he was considered an adult of maturity and authority, involved in managing family property and representing the interests of the Aberdeens in official matters.

John’s appearance in both the militia roll and the indenture suggests that he was part of the core generation of the Aberdeen free coloured family, one that came of age in the decades between his manumission in 1806 and emancipation in 1838. Like others of mixed heritage in this period, he navigated a complex colonial society, gaining civic responsibilities even as racial hierarchies persisted.

Although no known obituary survives for him, the pattern of his appearances suggests that he lived into the mid-nineteenth century and remained part of the network of free people of colour who increasingly shaped community life in Grenada.

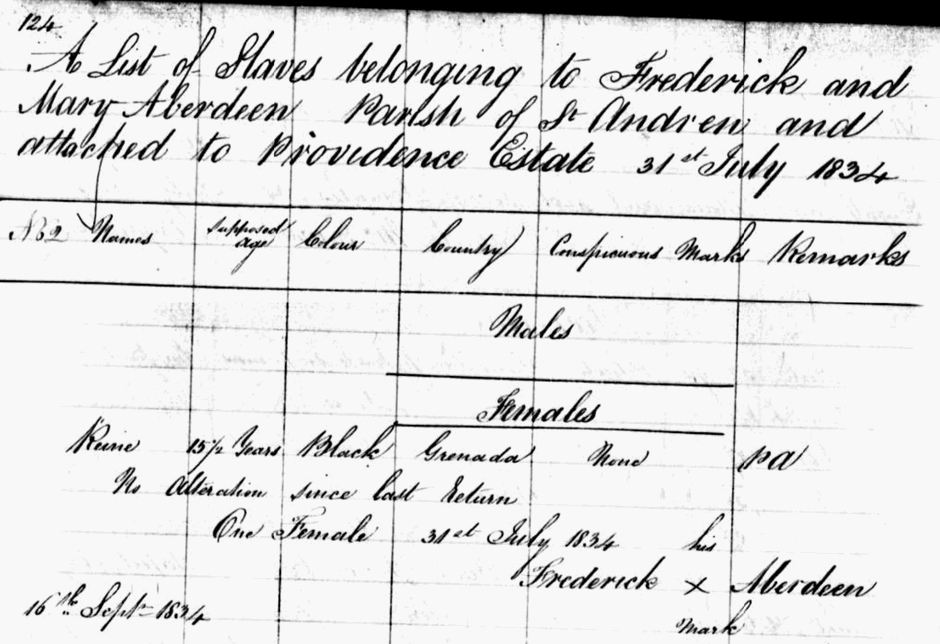

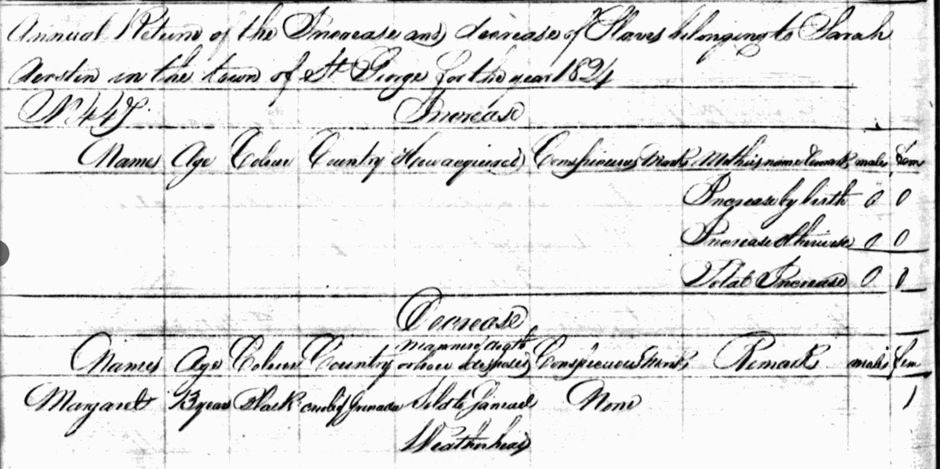

The Life of Barbara Aberdeen (c.1797 – 22 November 1867)

Barbara was named as Alexander Aberdeen’s reputed daughter and described as a free mulatto girl. She would have been about 18 when he died. Her life can be pieced together only from brief appearances in Grenada’s surviving records, but even these fragments show a woman who held responsibility during a period of profound change on the island. 1817:

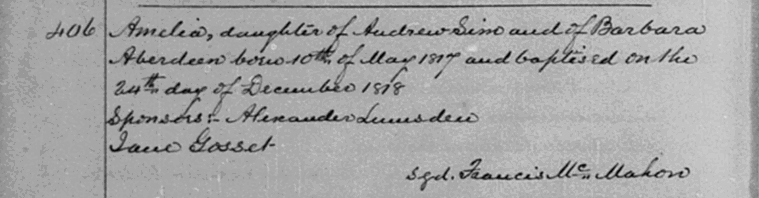

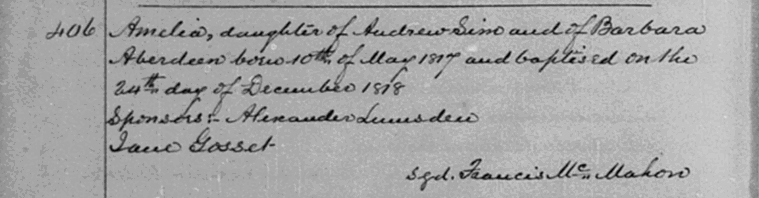

Mother of Amelia Sim

An 1818 baptismal record dated lists Amelia Sim, daughter of Andrew Sim and Barbara Aberdeen. She was born on 10 May 1817 and baptized on 24 December 1818 in St George’s. Ref

Barbara is carrying her maiden name on the certificate. As Andrew is named in the register and Amelia carried his name, it is likely that Barbara and Andrew were in a recognised relationship but not legally married.

Barbara is carrying her maiden name on the certificate. As Andrew is named in the register and Amelia carried his name, it is likely that Barbara and Andrew were in a recognised relationship but not legally married.

Given her estimated birth year of c.1797, Barbara would have been around 20 years old when Amelia was born.

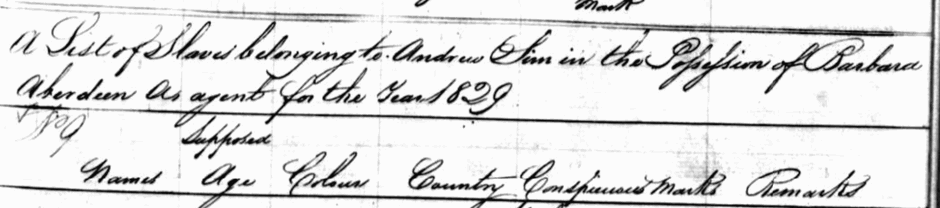

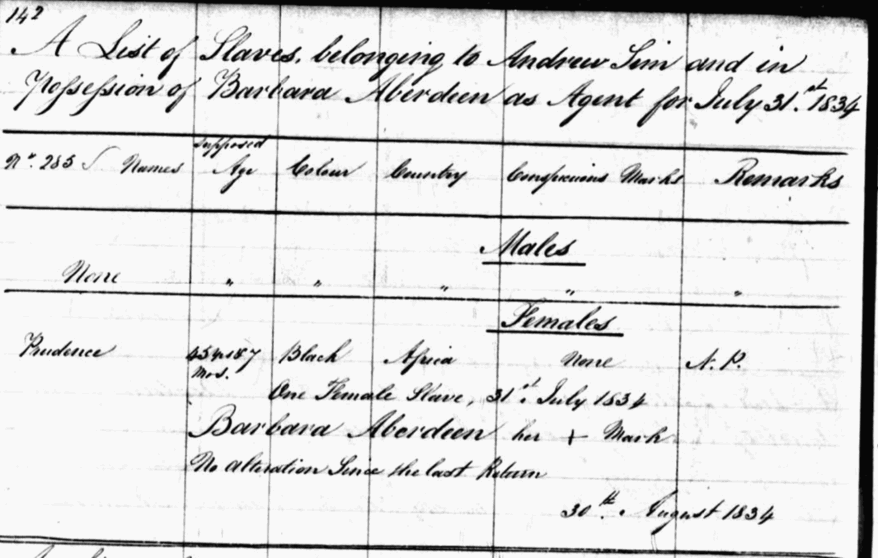

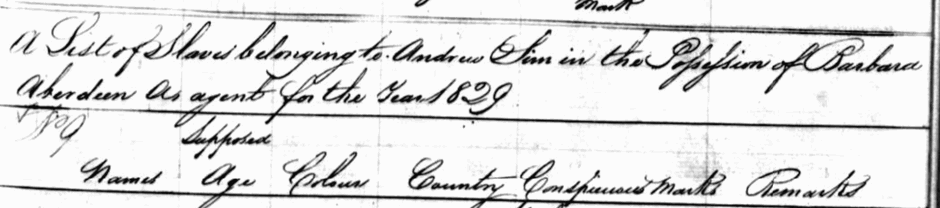

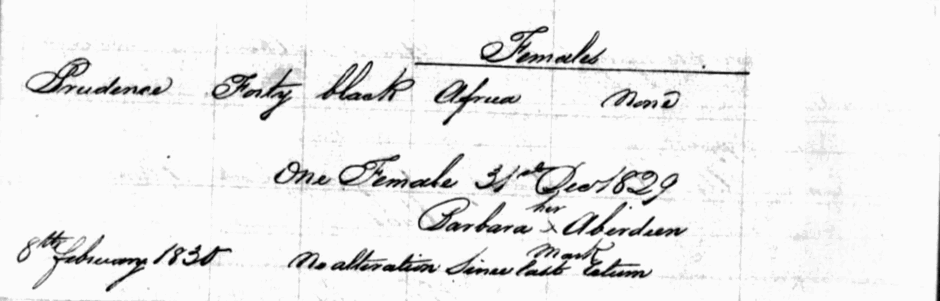

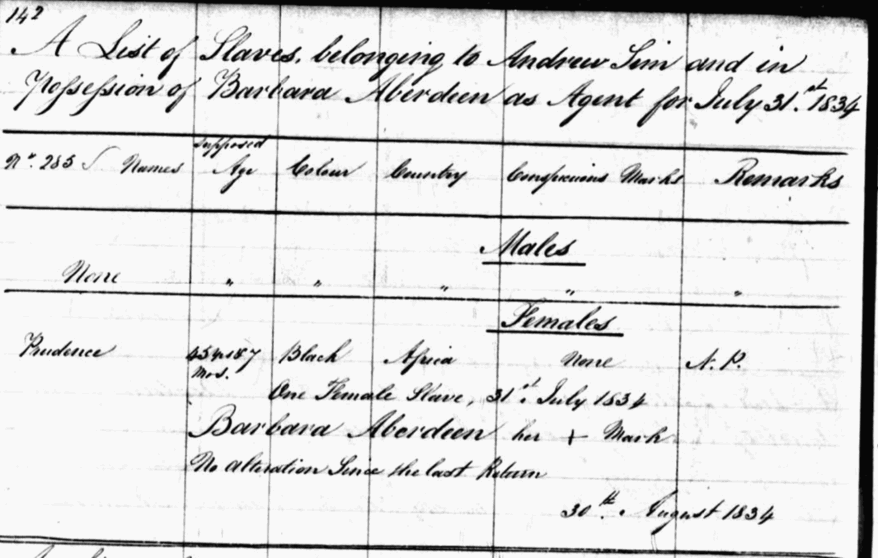

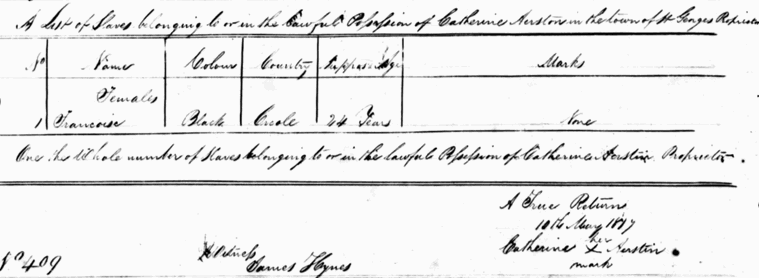

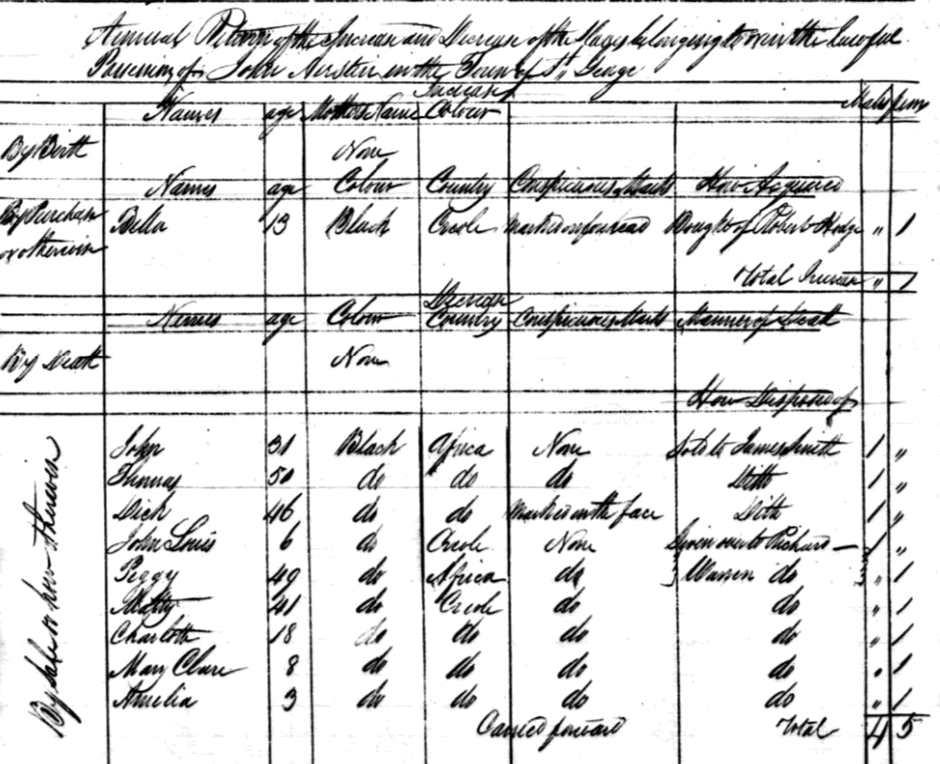

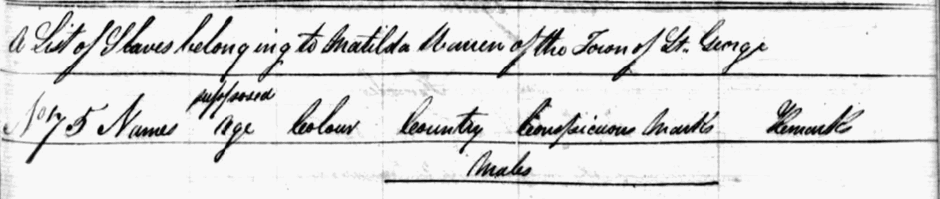

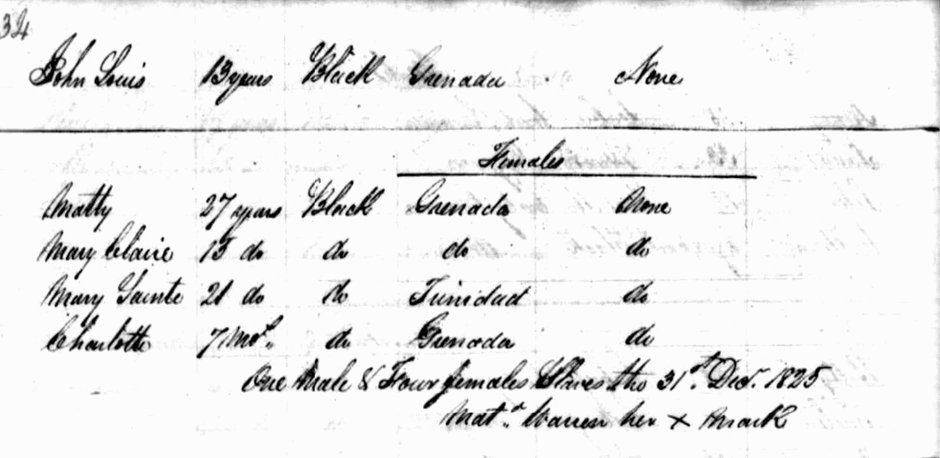

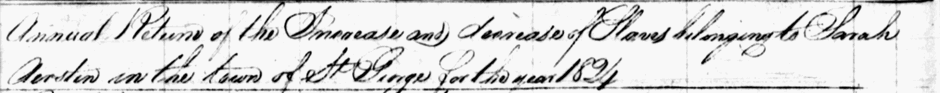

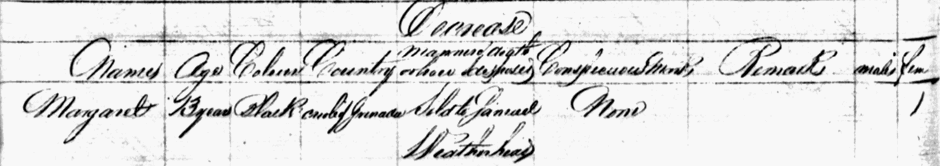

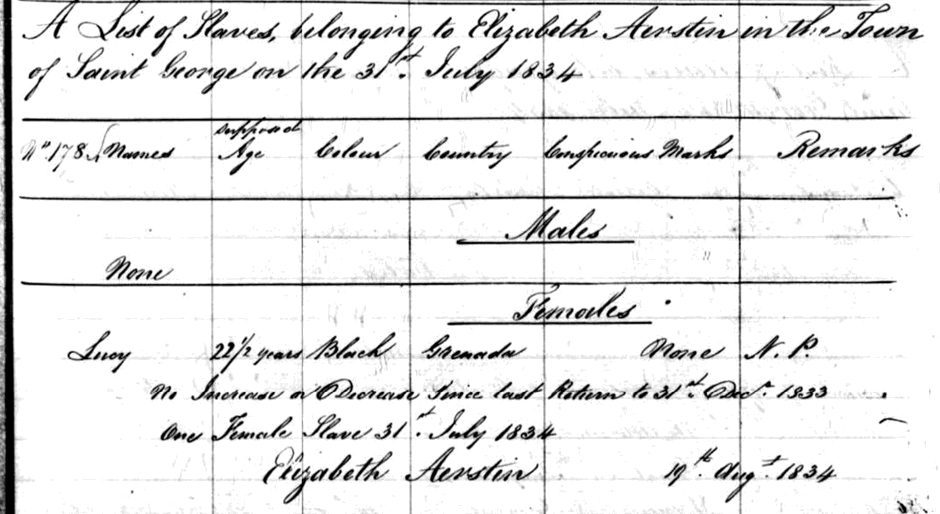

1829: Acting as an Agent in St Patrick

Barbara first appears in the 1828 and 1829 Slave Registers, where she is recorded as an agent for Andrew Sim in St Patrick. In that role, she submitted the registration of one enslaved person: Prudence, a 40-year-old African-born woman.

Her signature appears as an “X”, indicated she was illiterate.

As Prudence was the only enslaved person under their ownership, and a woman, it is possible that Prudence was brought in by Andrew to support Barbara in her domestic duties, Amelia would be about 10 years old.

Life Through Emancipation and Its Aftermath

Barbara lived through the apprenticeship period and the transition from slavery to full freedom in 1838. Although there is no record of her owning property or enslaved workers directly, it is clear that Prudence was brought in to support her and Barbara’s role as an agent in 1829 shows that she was familiar with colonial administrative processes.

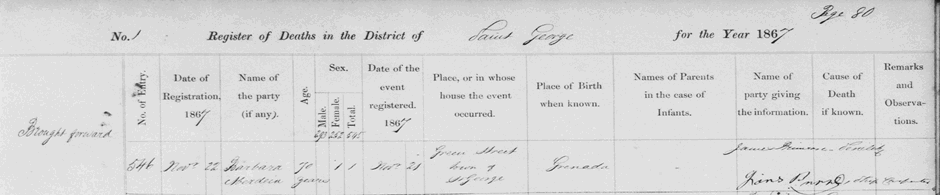

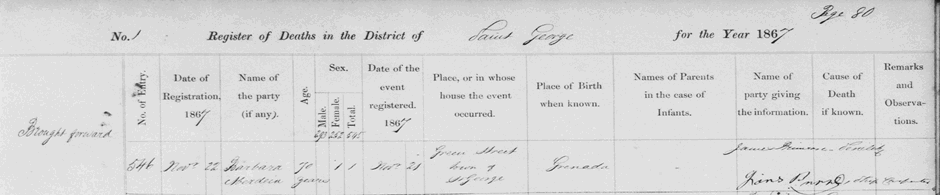

Death in 1867

Barbara Aberdeen died on 22 November 1867, aged 70 from “senility”. However, In the mid-19th century, the word “senile” simply related to old age. It did not specifically refer to dementia the way we use it today. Many doctors used “senility” simply as a respectable way of saying the person’s body had worn out.

Her lifetime spanned the height of plantation society and the aftermath following emancipation.

Her lifetime spanned the height of plantation society and the aftermath following emancipation.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

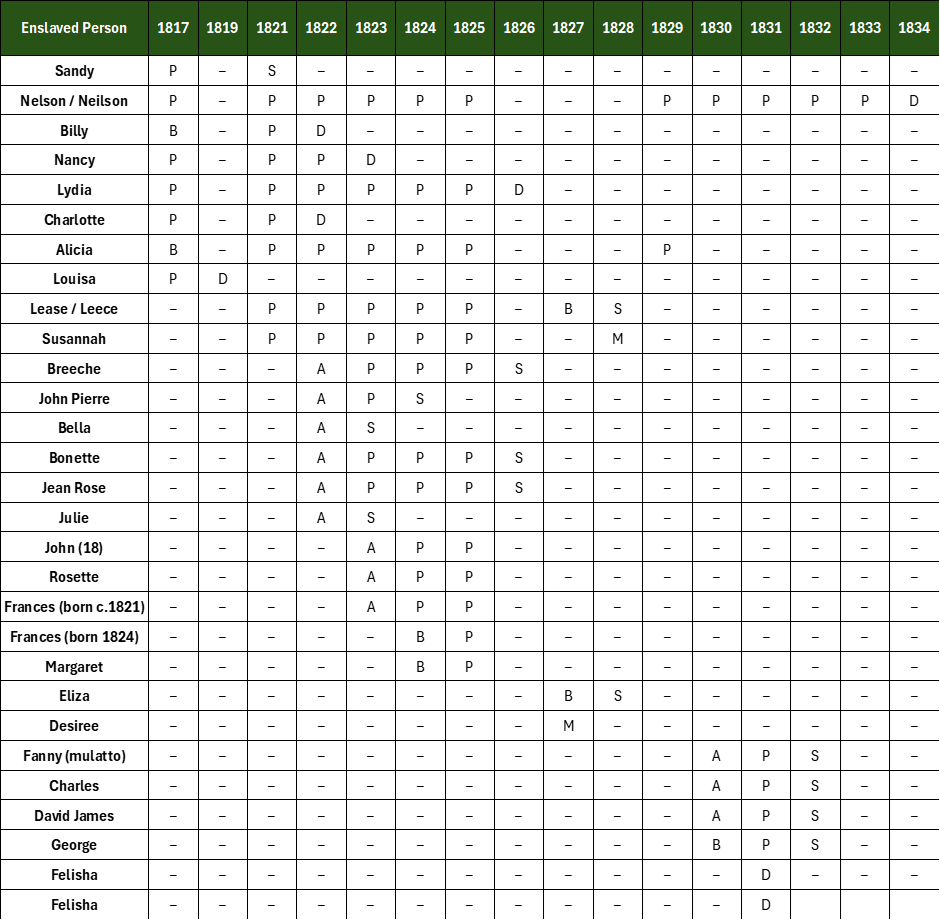

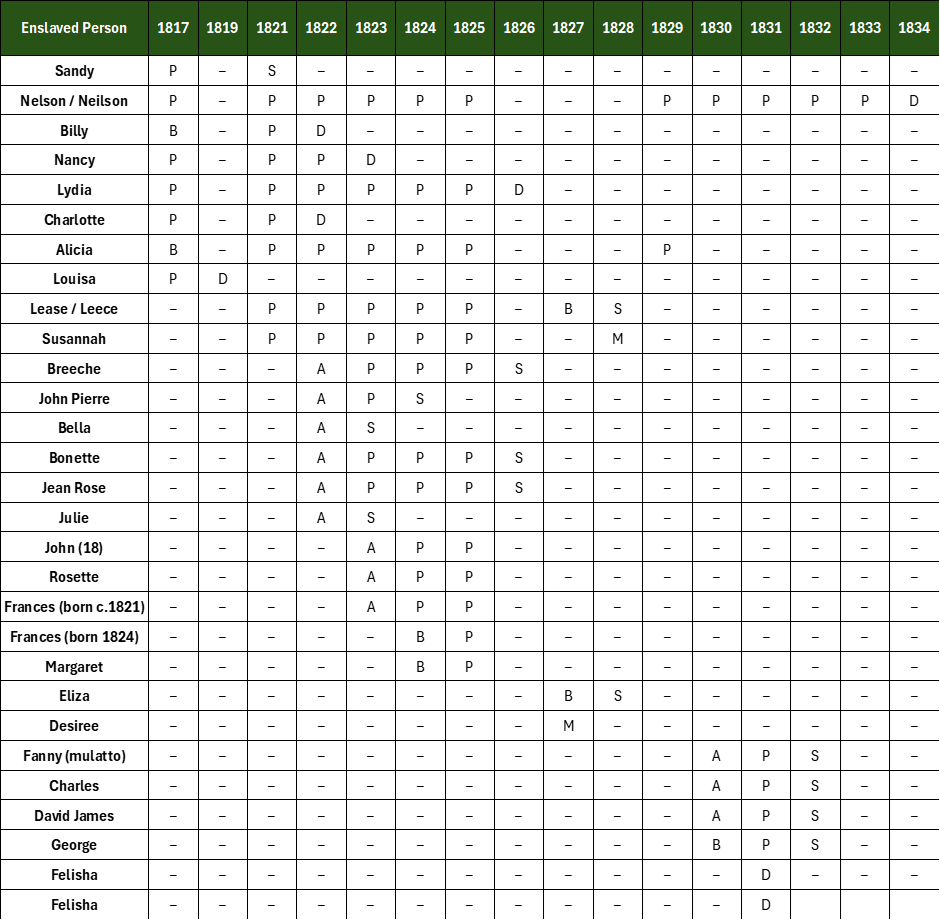

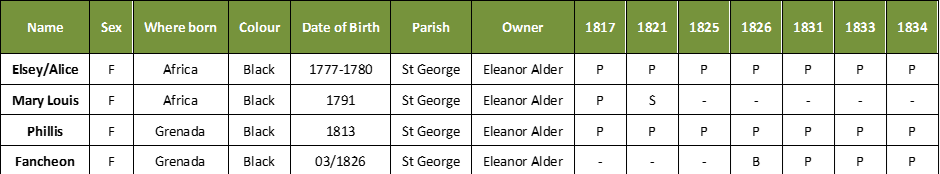

The Enslaved by Fanny Aberdeen

Table of Enslaved People held by Jane/Fanny Aberdeen by Year as recorded in the Slave Registers

Key:

A = Acquired

B = Born

D = Died

P = Present

M = Manumitted

S = Sold

SANDY (c.1777–after 1821)

Sandy was an African-born man who appeared on Fanny Aberdeen’s estate in 1817 at around 40 years old. Having survived the Middle Passage as a young adult, he worked for Fanny for at least four years until she sold him in 1821 to John Chapman. His sale suggests he remained physically capable despite decades of labour and trauma. Sandy’s life reflects the resilience of the African-born enslaved who endured removal, resettlement, and forced labour into late adulthood.

NEILSON / NELSON (c.1782–1834)

Nelson first appears in 1817 as a 35-year-old African man. He remained with Fanny through repeated deaths, sales, and restructurings, eventually becoming the last enslaved person she held. Nelson lived under Fanny’s ownership for at least 17 years, one of the longest-recorded relationships in the register. He died in 1834 of mal d’estomac. Despite his decades of survival his final years highlight the prolonged vulnerability of ageing African-born enslaved men.

BILLY (1812–1822)

Billy was born enslaved in Grenada and appeared in the 1817 register at age five. He grew up under Fanny’s control alongside Alicia, likely a sibling or close companion. In 1822, at just nine years old, he died of mal d’estomac. Billy’s short life reflects the precariousness of enslaved childhood in such places.

NANCY (c.1783–1823)

Nancy was an African-born woman aged 34 in 1817. She lived and laboured on Fanny’s estate for at least six years and died in 1823 at around 40 years old from mal d’estomac. Her death, like several others on Fanny’s estate, reflects a pattern of suffering among African-born women, who often bore the greatest emotional, physical, and reproductive burdens.

LIDIA / LYDIA (c.1783–1826)

Lydia, an African-born woman, first appears at age 34. She remained with Fanny for nearly a decade. She likely participated in heavy labour and possibly mentoring younger Creole-born enslaved people. Lydia died in 1826 at age 41. Her long presence there underscores the reliance on African women in sustaining plantation workforces after the slave trade ended.

CHARLOTTE (c.1784–1822)

Charlotte was a 33-year-old African woman in 1817. She lived under Fanny’s ownership for at least five years and died in 1822 at about 37, also from mal d’estomac. Her record is one among several African women under Fanny’s control who died young from conditions linked to trauma and deprivation.

ALICIA (1812–after 1829)

Alicia, born enslaved in Grenada in 1812, was recorded with Fanny from age five into her teenage years. She survived childhood deaths, repeated sales, and the dispersal of her companions. By 1829, she and Nelson were the only two enslaved people left with Fanny. After this she disappears from the record.

LOUISA (c.1777–1819)

Louisa was a 40-year-old African-born woman in 1817 and died two years later, aged 42, after suffering from “lame legs” and mal d’estomac’.

LEASE / LEECE (c.1795–1828)

Lease was a Creole woman born around 1795. She lived on Fanny’s estate from at least 1821 until she and her infant daughter Eliza were sold to Tomas Castale in 1828. She gave birth to a daughter, Eliza, in 1827, only to be sold the following year highlighting the fragility of enslaved family life. Her fate after sale is unknown.

SUSANNAH (c.1808–manumitted 1828)

Born in Grenada around 1808, Susannah appeared as a teenager on Fanny’s estate and lived there throughout the turbulent 1820s. In 1828, at around 25 years old, she obtained her manumission from Fanny. She is one of the few enslaved people associated with Fanny whose freedom was formally secured before full emancipation.

BRECHE / BREECHE (c.1790–after 1826)

Breeche was an African-born man, aged 32 in 1822. He remained with Fanny until 1826, when he was sold back to Julien Allan Delatouche. His sale suggests he retained economic value and physical ability despite the intense labour of his thirties. His trajectory reflects the common cycle of purchase, exploitation, and resale.

JOHN PIERRE (c.1775–sold 1824)

John Pierre, a 47-year-old African-born man, was purchased by Fanny in 1822 and sold back to Delatouche two years later.

BELLA (c.1781–sold 1823)

Bella was a 41-year-old African-born woman purchased in 1822. She was sold back to Delatouche in 1823, along with Julie. Her brief ownership shows the instability of enslaved women’s lives and the frequency of rapid turnover even in small holdings.

BONNETTE / BONNET / RENETTE (1811–sold 1826)

Born in Grenada in 1811 and identified as a mulatto, Bonette was bought by Fanny in 1822. At age 15 she was sold back to Delatouche. Her early sale, before childbearing age, may indicate domestic training or perceived market value. Her life embodies the vulnerability of mixed-race children in the colonial slave economy.

JEAN ROSE (1809–sold 1826)

Jean Rose was a Creole girl born around 1809. Acquired in 1822 at age 13, she remained with Fanny until 1826, when she too was sold back to Delatouche.

JULIE (c.1798–sold 1823)

Julie was a young African-born woman, aged 24 when Fanny purchased her. She was sold back to Delatouche the following year. Her brief appearance suggests Fanny frequently traded enslaved women for profit or restructuring.

JOHN (c.1803–after 1825)

John, aged 18 in 1823, was purchased and registered under “Jane.” In 1825 he was recorded as 20 years old on that same estate. His movements reflect a secondary property portfolio Fanny operated alongside her primary one.

ROSETTE (c.1797–after 1825)

Rosette, purchased in 1823 at about 26 years old, was recorded as a mother by 1825, having given birth to Margaret. Her life reflects the forced reproductive role imposed on enslaved women, whose children enlarged the labour force.

FRANCES (born 1821/1824)

There were two girls named Frances: Frances (born c.1821) Purchased in 1823 as a two-year-old, she lived on the estate attached to Jane Aberdeen’s secondary property. She appears again in 1825, aged four. Frances (born 1824)Born on Fanny’s main location, this infant’s birth was recorded in the 1825 register. She grew up in an environment of sales, deaths, and shrinking household numbers; nothing further is recorded about her after early childhood.

MARGARET (born 1824)

Born to Rosette on Jane’s secondary location, Margaret symbolises the continuation of enslaved family lines despite the absence of stability or protection from sale. She was recorded at age one in 1825.

ELIZA (born 1827)

Eliza was born to Lease in 1827. She was sold with her mother to Tomas Castale in 1828 when she was only one year old. Her forced removal as an infant was typical of the era and demonstrates how enslaved families were routinely fractured.

DESIREE (c.1824–manumitted 1827)

Desiree, aged three in 1827, was manumitted that same year. She is the youngest person in Fanny’s records to obtain freedom, likely reflecting a specific request or negotiated arrangement.

FANNY (c.1807–sold 1832)

Purchased in 1830 and described as a 23-year-old mulatto woman, she arrived with her three young sons. They formed a rare intact family group on Fanny’s estate. In 1832, the entire family was sold to Catherine Drysdale.

CHARLES (born c.1823–sold 1832)

A seven-year-old mulatto child purchased as part of the above family unit. He was sold with his mother and brothers in 1832.

DAVID JAMES (born 1828–sold 1832)

Brought under Fanny’s control as a 19-month-old baby in 1830. He was sold at around 3¾ years old to Catherine Drysdale in 1832.

GEORGE (born 1829–sold 1832)

A 3½-month-old infant in 1830, George was sold at 2¼ years old with the rest of his family in 1832. His presence shows his mother had recently given birth before being taken by Fanny.

FELISHA (c.1815–1831)

Felisha was a 16-year-old girl who died in 1831 of mal d’estomac. Her youth, gender, and the manner of her death underline the emotional and physiological toll that enslavement inflicted on adolescents.

SUMMARY

Across the years 1817 to 1834, more than thirty enslaved people lived, laboured, were born, died, bought, or sold on the small St Andrew estate managed by Jane “Fanny” Aberdeen. Their lives reflect the broader instability of Grenadian slavery in its final decades, as well as the human endurance required to survive it.

The 1817 register shows a workforce dominated by African-born men and women, Sandy, Nelson, Nancy, Lydia, Charlotte and Louisa, who had survived the Middle Passage years earlier and were forced into hard labour as middle-aged adults. They formed the backbone of the work force, working alongside one another until death or sale removed them from the records. Several died from mal d’estomac, a term associated with extreme trauma, starvation, illness and the psychological suffering of enslavement.

The creole born children grew up in constant insecurity. Billy and Alicia, both born in Grenada and registered at age five, symbolise the vulnerability of enslaved childhood. Billy died by age nine from mal d’estomac, while Alicia survived into adulthood but ultimately disappeared from the records. Other children, like Frances (1824), Margaret (1824), Desiree (1827), and Eliza (1827), were born into slavery only to be sold, manumitted, or removed within a few years.

Families existed but were often broken apart. Lease and her daughter Eliza were sold together in 1828. Rosette and her daughter Margaret, were kept together. Fanny and her three sons (Charles, David James, and George) were purchased as a unit and sold together two years later. But other family ties were severed repeatedly. Infants and toddlers were frequently sold or died young, and family groups were transferred between places, bought back by former owners, or separated permanently.

Fanny Aberdeen regularly bought enslaved people in batches, particularly in 1822 and 1830, and just as often sold them back into the market. Adults such as Bella, Julie, John Pierre, Breeche, Bonette, and Jean Rose were acquired and then eliminated through sale only a few years later. Every enslaved person lived with the knowledge that they could be removed at any moment.

A small number achieved manumission. Two individuals; Susannah (1828) and Desiree (1827) were freed by Fanny. They were rare exceptions in a system otherwise defined by perpetual bondage.

Death from distress and deprivation was common. Multiple individuals; Louisa, Billy, Charlotte, Nancy, Felisha, and finally Nelson died of mal d’estomac. Many died in their 30s and 40s, consistent with the life-shortening effects of plantation labour, high stress, hunger, abuse, and chronic trauma.

By the early 1830s, only Nelson and Alicia remained from the original group. After Alicia disappeared from the records, Nelson stood there alone. He died in 1834 and was the last enslaved person held by Fanny Aberdeen.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mal d’estomac

In the 1800s, when an enslaved person in Grenada was recorded as dying from mal d’estomac (“stomach disorder”), it often referred to a condition linked to dirt-eating, known medically as pica, but described by plantation doctors as Cachexia Africana.

Many enslaved Africans continued the longstanding cultural practice of consuming certain types of clay, something widely done across Africa, the Americas, and Indigenous societies for medicinal, dietary, or spiritual reasons. But in the Caribbean plantation environment, their attempts to recreate this practice were misunderstood and forbidden.

Enslaved people ate earth for reasons including hunger, stress, malnutrition, cultural continuity, mineral supplementation, and psychological survival. But planters and doctors saw the behaviour as a “disease,” blaming the supposed weakness of African bodies rather than the brutal conditions of slavery. Instead of recognising the role of starvation, trauma, and deprivation, they labelled the habit mal d’estomac or simply “dirt-eating,” claiming it was fatal and widespread.

European women who suffered from pica for similar reasons, pregnancy, anaemia, stress were treated gently and seen as curable. Enslaved Africans, however, were seen as mentally flawed or physically inferior, and the same behaviour was considered deadly. Plantation doctors frequently wrote that many enslaved people who developed the habit were “lost,” and some claimed that half of plantation deaths were caused by this so-called disorder.

In reality, the deaths often stemmed from malnutrition, poor sanitation, untreated infections, parasites, dehydration, and the extreme physical and psychological pressures of enslavement. The label mal d’estomacprovided planters with a convenient explanation that hid the true causes of illness and mortality on estates.

Thus, death by mal d’estomac in Grenada was largely a product of cultural misunderstanding, medical racism, and the harsh realities of plantation life. It reflected the gulf between African knowledge systems and European plantation medicine, and it exposed the ways enslavers used pseudoscience to blame enslaved Africans for the suffering that slavery itself inflicted.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

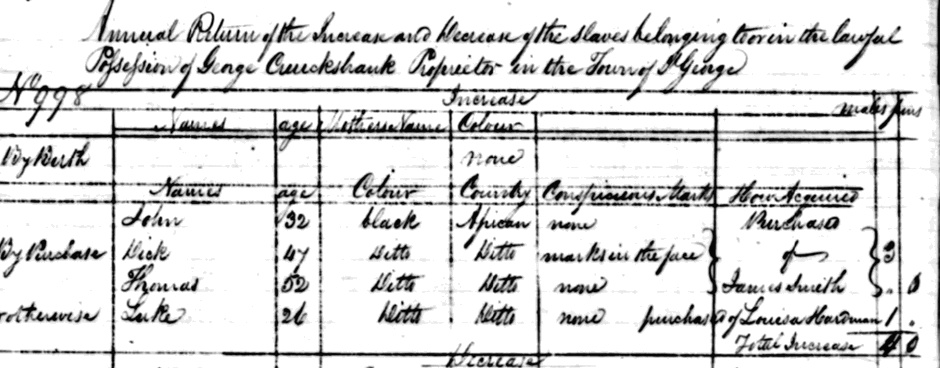

The Enslaved by Barbara Aberdeen

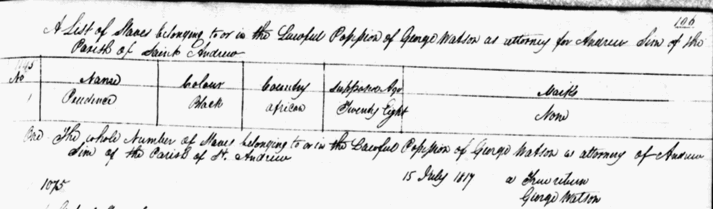

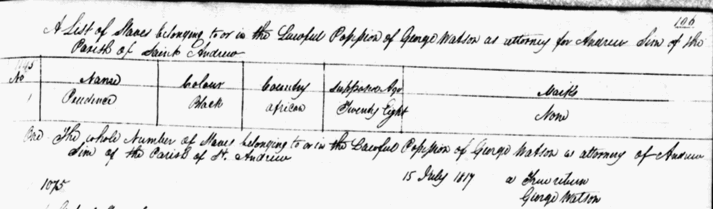

Prudence was born in Africa and was forced into the transatlantic slave trade. She survived the Middle Passage and first appears in Grenada’s records in 1817, legally owned by Andrew Sim but in the possession of George Watson.

Since she was born in Africa, there is no record of her actual date of birth but she is estimated to have been born in 1789 so would have been about 28 in 1817.

By 1828 she was in the possession of Barbara Aberdeen, likely working in her home where she would have performed domestic work such as cooking, washing, cleaning and tending a garden. Prudence may also have helped to raise Barbara’s daughter, Amelia and have been the steady, grounding adult in the household who quietly kept everything running.

She is seen again in the 1829, 1833 and finally 1834 slave registers under Barbara Aberdeen.

She worked for Andrew Sim for at least 17 years. Her character emerges here as a dependable, capable and trustworthy person.

Now aged about 45 years old, she lived long enough to see slavery end and to enter the apprenticeship system that followed.

Though the archive records little more than her name, age, and origin, the continuity of Prudence’s life suggests a woman of quiet strength, resilience, and dignity. She was someone who endured profound upheaval yet remained a steady presence through decades of change in Grenada.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support and Owen Hankey for content contributions.

Example Text

er workforce rose to six.

er workforce rose to six.

In the 1846 indenture relating to Fanny Aberdeen’s property, he appears as one of the executors of her estate, together with his brother Alexander Aberdeen. Being named as an executor indicates that John was trusted, literate, and capable of handling legal responsibilities. It also shows that by the mid-nineteenth century he was considered an adult of maturity and authority, involved in managing family property and representing the interests of the Aberdeens in official matters.

In the 1846 indenture relating to Fanny Aberdeen’s property, he appears as one of the executors of her estate, together with his brother Alexander Aberdeen. Being named as an executor indicates that John was trusted, literate, and capable of handling legal responsibilities. It also shows that by the mid-nineteenth century he was considered an adult of maturity and authority, involved in managing family property and representing the interests of the Aberdeens in official matters.

Barbara is carrying her maiden name on the certificate. As Andrew is named in the register and Amelia carried his name, it is likely that Barbara and Andrew were in a recognised relationship but not legally married.

Barbara is carrying her maiden name on the certificate. As Andrew is named in the register and Amelia carried his name, it is likely that Barbara and Andrew were in a recognised relationship but not legally married.

Her lifetime spanned the height of plantation society and the aftermath following emancipation.

Her lifetime spanned the height of plantation society and the aftermath following emancipation.

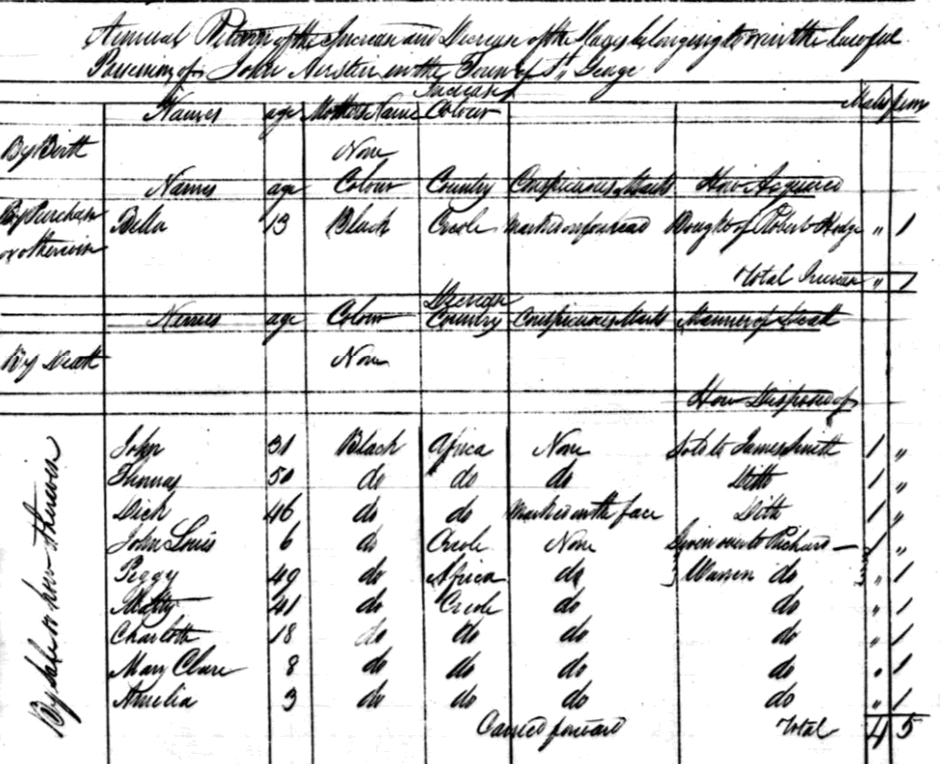

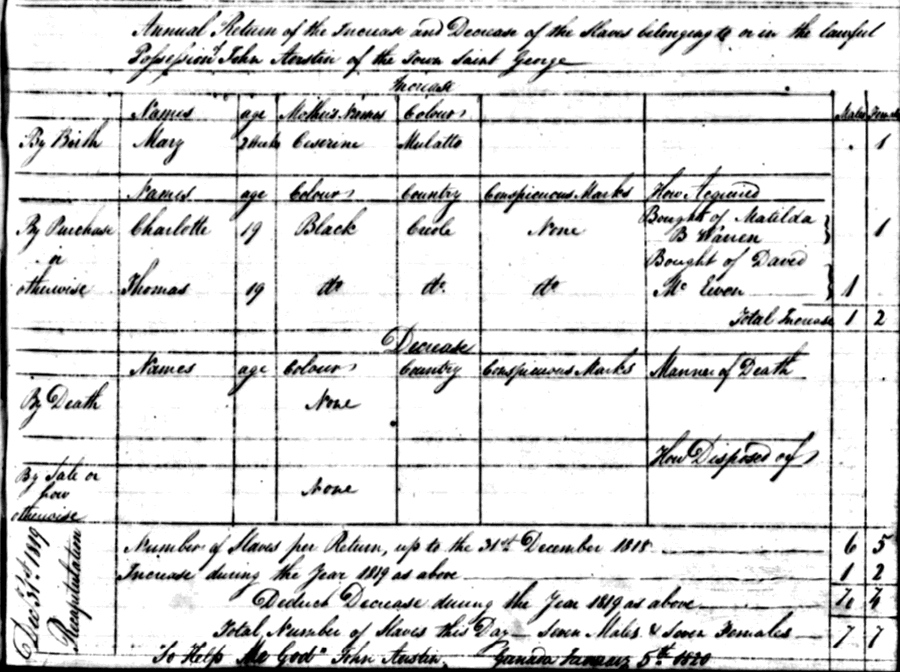

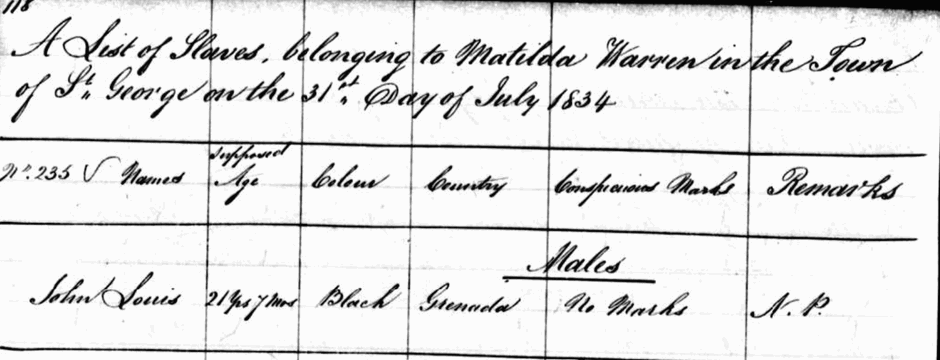

John enslaved two more people that year; Charlotte from Matilda B. Warren (perhaps the same Charlotte that was sold the year before) and Thomas from David McEwen. They were both 19 years old.

John enslaved two more people that year; Charlotte from Matilda B. Warren (perhaps the same Charlotte that was sold the year before) and Thomas from David McEwen. They were both 19 years old.

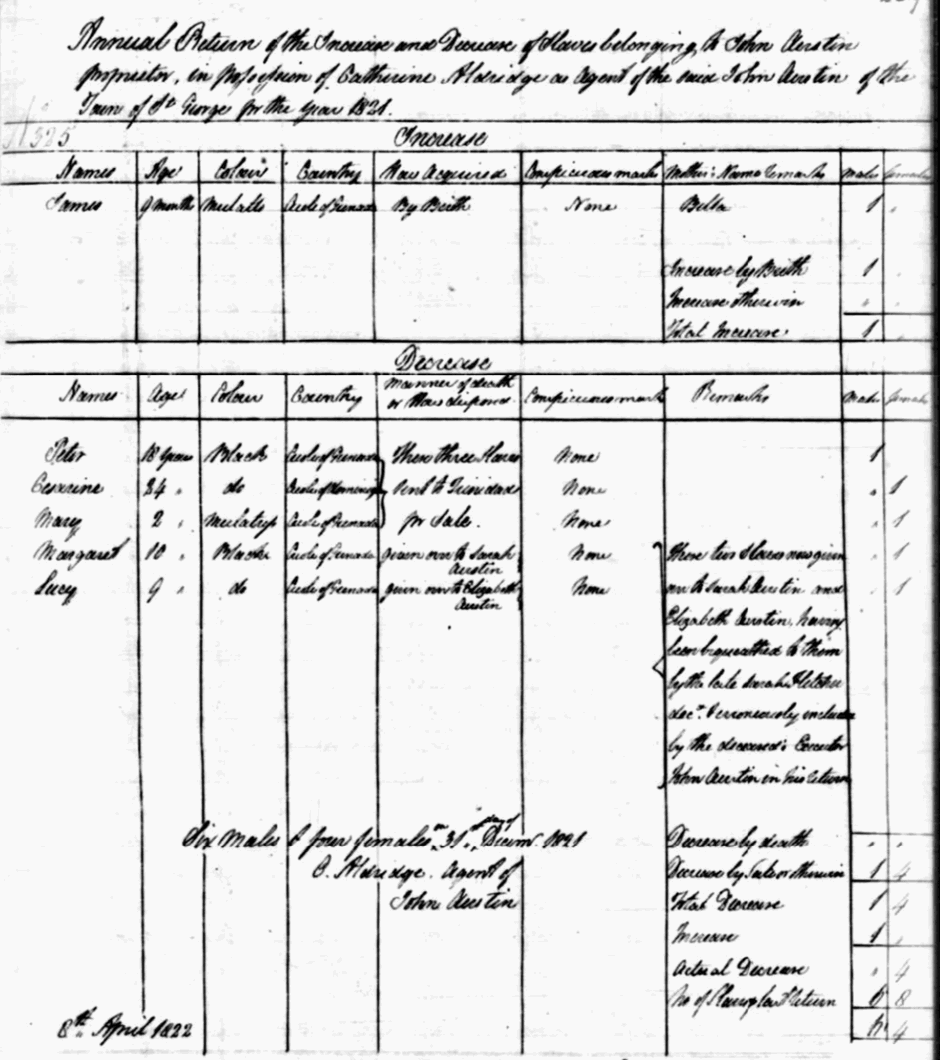

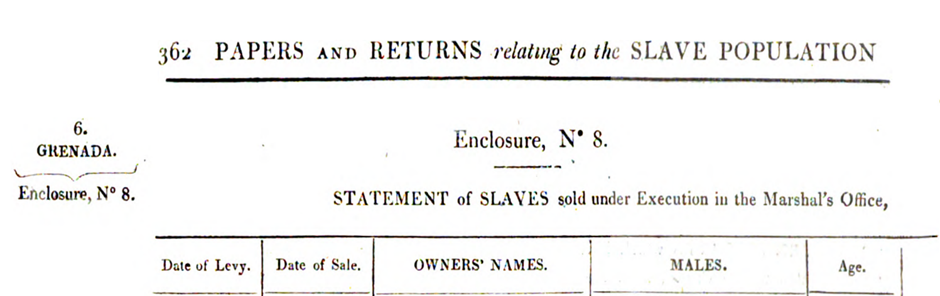

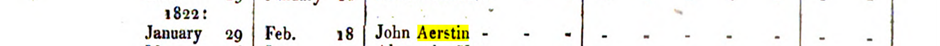

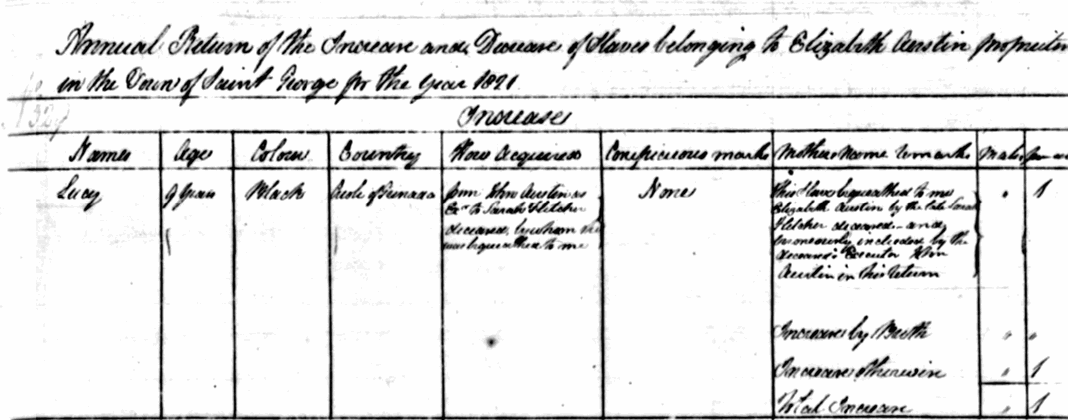

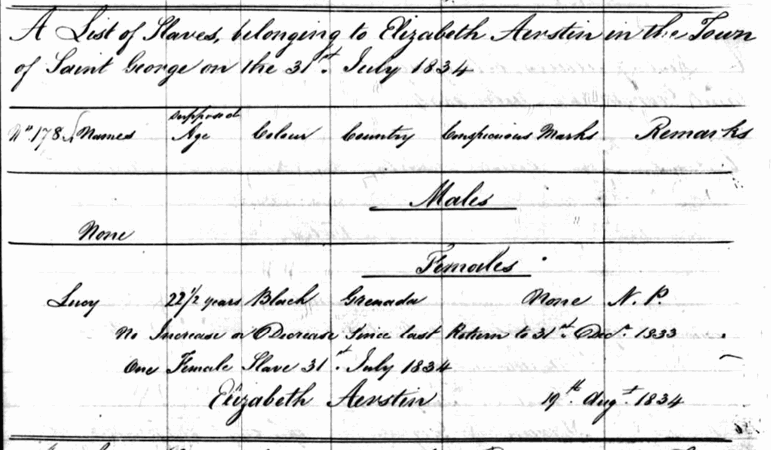

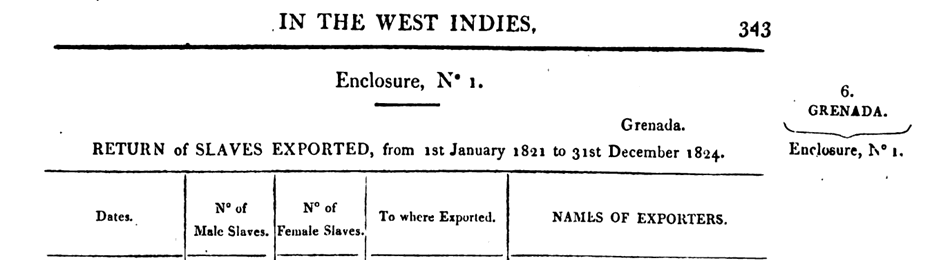

Peter, Cesarine, and May were shipped to Trinidad for sale, while Margaret and Lucy were transferred to Sarah and Elizabeth Aerstin respectively under a contractual arrangement tied to the late Sarah Fletcher, John was the executor of her will. It is likely that he was closely related to Sarah and Elizabeth in some way. There is a record of John AERSTIN selling an enslaved worker under execution in the Marshall’s office on 18 Feb 1822.

Peter, Cesarine, and May were shipped to Trinidad for sale, while Margaret and Lucy were transferred to Sarah and Elizabeth Aerstin respectively under a contractual arrangement tied to the late Sarah Fletcher, John was the executor of her will. It is likely that he was closely related to Sarah and Elizabeth in some way. There is a record of John AERSTIN selling an enslaved worker under execution in the Marshall’s office on 18 Feb 1822.

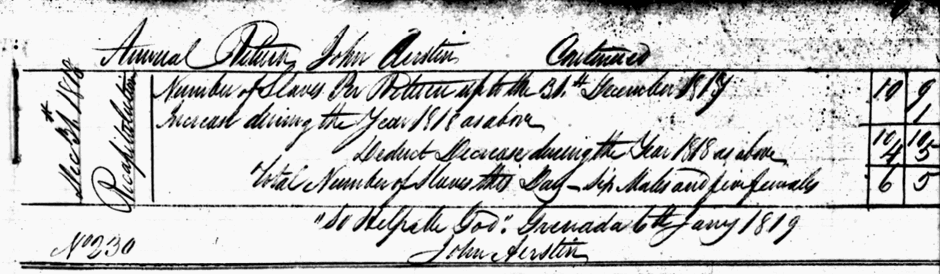

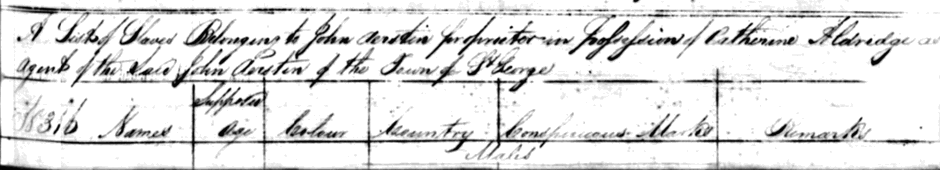

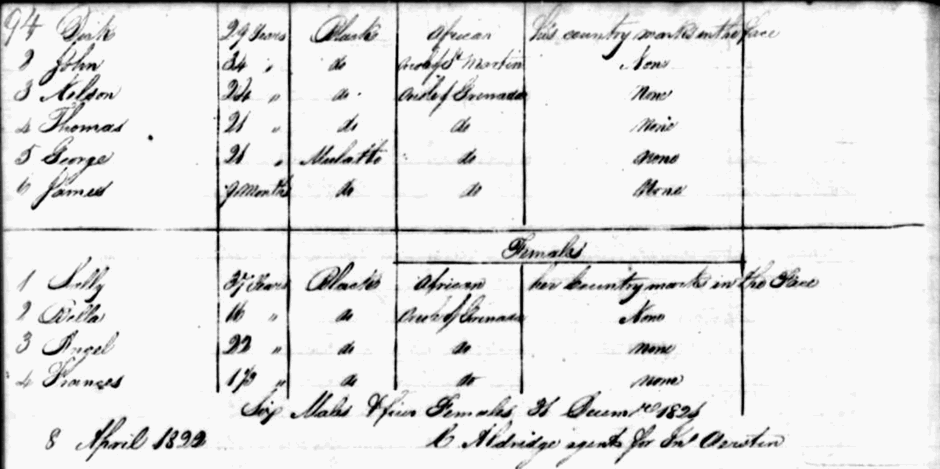

The Slave Register of this year, again under the possession of Catherine Aldridge showed 6 males and 4 females under his control. James was 9 months old.

The Slave Register of this year, again under the possession of Catherine Aldridge showed 6 males and 4 females under his control. James was 9 months old.

He likely died before emancipation, which would explain why no compensation claim exists under his name. There is also a

He likely died before emancipation, which would explain why no compensation claim exists under his name. There is also a

Sarah AERSTIN was also included in the 1821 register. She is listed as the owner of Margaret, a ten-year-old bequeathed to her by the late Sarah Fletcher under the same executor, John Aerstin, like Elizabeth. Sarah’s small-scale ownership resembles Elizabeth’s.

Sarah AERSTIN was also included in the 1821 register. She is listed as the owner of Margaret, a ten-year-old bequeathed to her by the late Sarah Fletcher under the same executor, John Aerstin, like Elizabeth. Sarah’s small-scale ownership resembles Elizabeth’s.

This was the last we saw of Thomas.

This was the last we saw of Thomas.

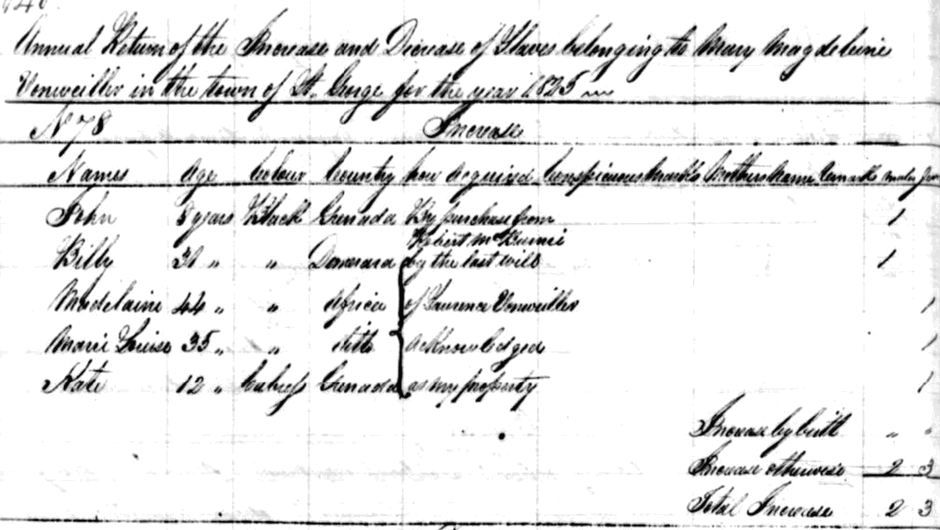

She was bequeathed to Magdeleine together with Billy (31), Madelaine (44) and Kate (12), who she knew from her time with Lawrence. She was also joined by John (8) who had been purchased from Robert McBurnie.

She was bequeathed to Magdeleine together with Billy (31), Madelaine (44) and Kate (12), who she knew from her time with Lawrence. She was also joined by John (8) who had been purchased from Robert McBurnie.