Hortense Watson

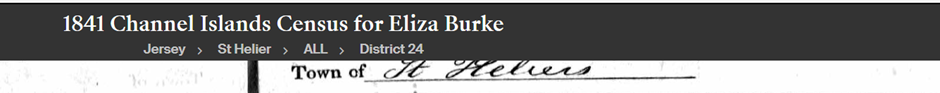

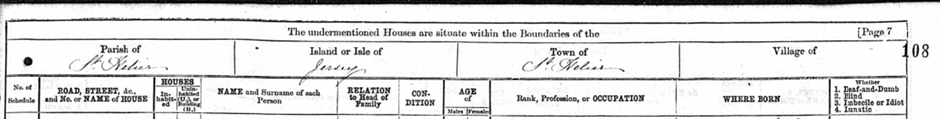

1841 Census

The 1841 census in Jersey shows Hortense Watson, aged 20, as a servant in the residence of William and Eliza BURKE. Though it was noted that she was born outside of Jersey, this was sometimes interpreted as not born in England, Scotland, Ireland or “foreign parts”, but born in the British Empire.

William and Eliza were planters in Grenada and had recently moved St Helier, Jersey at an address at Windsor Crescent, Trinity Road.

Hortense must have been regarded highly by the family as she was bequeathed an annual annuity for life of £15 from William Burke when he died in 1850.

On researching the Slave Register, it seems apparent that she was likely born in Grenada and brought over to Jersey with the Burkes.

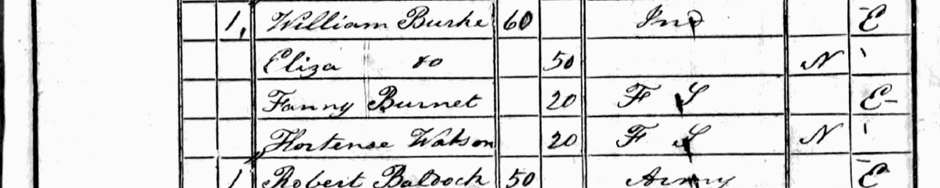

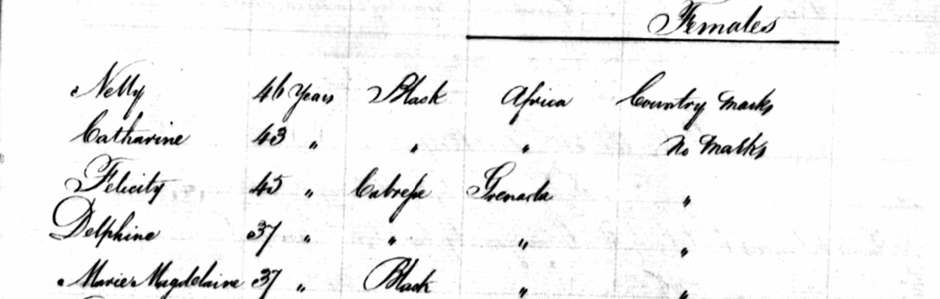

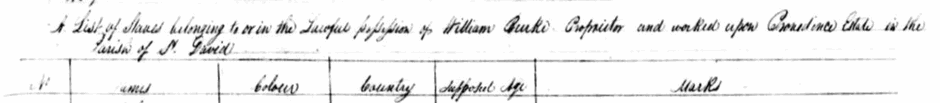

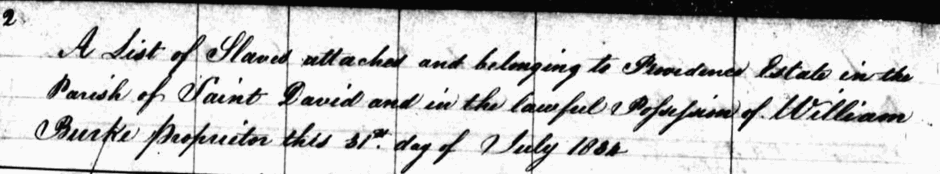

1821 Slave Register

This Slave Register records a Hortense living on the estate of Eliza’s grandmother, (Elizabeth Langaigne) born in 1821. The register shows that Hortense was born enslaved as the daughter of a Marie Magdelaine (who was 29 at the time), and was described as being black.

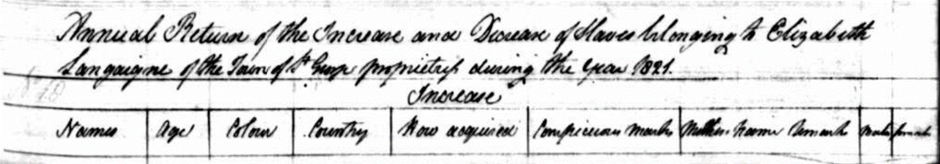

1829 Slave Register

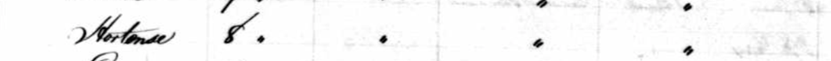

We see Hortense again in the 1829 slave register, age 8, living with her mother Marie Magdeleine (now age 37).

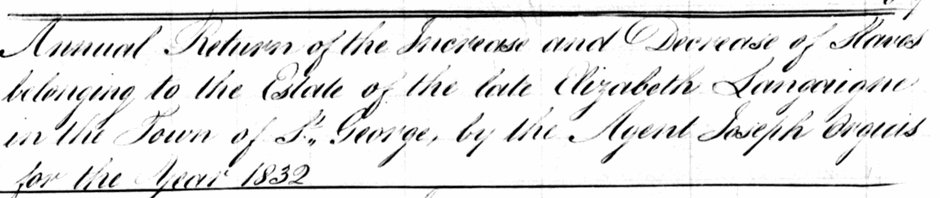

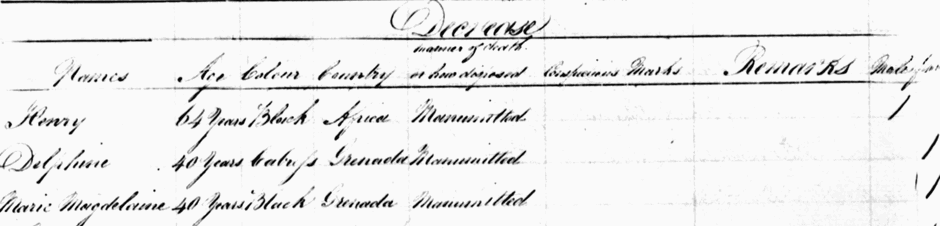

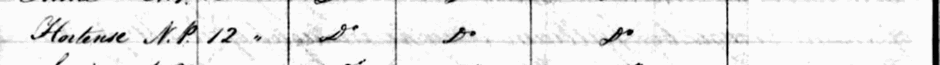

1832 Slave Register

Marie was manumitted in 1832 after Elizabeth LANGAIGNE had died but there are no records showing that Hortense was freed at the same time.

1834 Slave Register

In fact, Hortense was listed enslaved on the estate in 1834, aged 12. This register is significant as it shows the rapid change of ownership. William Burke acquired the estate of the late Elizabeth Langaigne following her death and that her son Louis Felix Langaigne who departed shortly afterwards leaving Eliza Burke as the heir who was William’s wife.

Hortense had lived her life enslaved at this point and released sometime between 1834 and 1838 before being taken to Jersey.

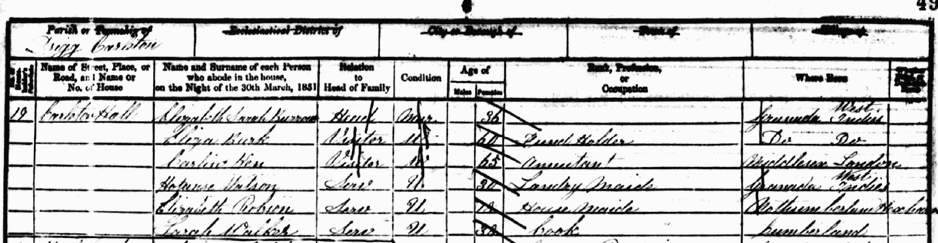

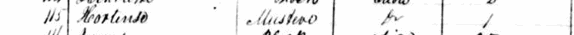

1851 Census

The 1851 Census shows that, after William had died, Hortense followed Eliza to live with her daughter, Elizabeth Sarah BURROW at her husband’s ancestral home at Carleton Hall, Cumberland. She was 30 and employed as the family’s laundry maid.

CARLETON HALL - 29/08/2000 © Mr Julian Thurgood. Source: Historic England Archive

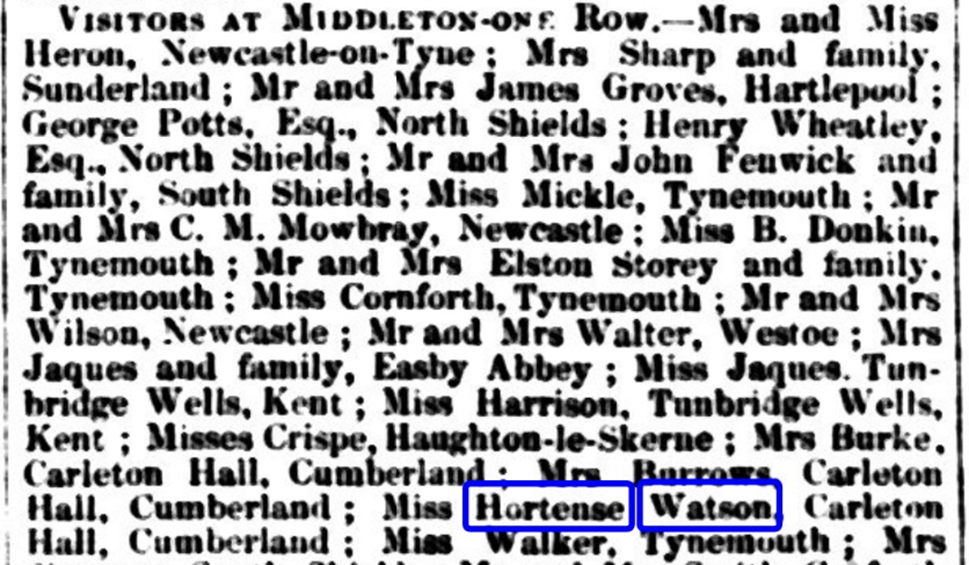

Spa Visit 1854

In the late summer of 1854, Hortense Watson travelled from Cumberland to Middleton-on-the-Row with the household of Carleton Hall. The journey itself would have been a modern one. By that date, the Stockton & Darlington Railway (opened in 1825, the world’s first public steam railway) was well established, and Middleton St George and nearby Dinsdale were directly served by the line. The railway had transformed the area into an accessible spa destination, allowing visitors from Cumberland, Newcastle, Tynemouth, and the wider north-east to travel comfortably and respectably, without the expense or inconvenience of long coach journeys.

Trains made it possible for whole households to travel together, and reinforced Middleton-on-the-Row’s reputation as a modern, fashionable retreat. Hortense’s presence in the visitor list therefore sits within a wider story of mobility after enslavement: she was able to move through Britain using the same infrastructure as other respectable travellers, participating in a world reshaped by railways, leisure, and visibility.

From Carlisle the train ran south through the Pennines to Darlington, before continuing to Dinsdale station, less than a mile from Middleton. What would once have been an exhausting coach journey could now be completed in a single day by women travelling together.

Middleton-on-the-Row was a recognised spa and leisure destination, shaped by the mineral springs at nearby Dinsdale and by its position on the river. Visitors came in search of health and for riverside walks, polite conversation, and the ritual of being seen among others of similar standing.

During the season, newspapers such as the Darlington and Stockton Times published lists of visitors staying in the area, a practice that served both as social record and public validation. To appear in print was to be acknowledged as part of respectable society. It was in this context that Eliza Burke, Elizabeth Burrow, and Hortense Watson appeared in the newspaper of 28 September 1814 together with other members of the provincial gentry, professionals, and well-to-do families from northern England.

It is interesting to see that Hortense was named in full but Eliza and Elizabeth’s names were left more formally as Mrs Burtke and Mrs Burrow. This conforms with Victorian newspaper conventions. Analysis of 19th-century provincial newspapers shows consistent patterns. Family groups listed as “Mr and Mrs X”, “Mrs and Miss X”, or “Mr and Mrs X and family”. Their individual names were assumed to be known or unimportant to the public record. Independent unmarried women listed as “Miss + full name”. Servants were almost never named, and if mentioned, described functionally rather than personally. These patterns are well documented in local history studies and routinely used by social historians when interpreting visitor lists.

The fact that Hortense is named and styled “Miss” is therefore exceptional, it gave her a standing within the society as a respectable, unmarried woman travelling with a known household.

The quiet significance of this moment lies in its ordinariness. Nothing in the notice explains who Hortense was or where she had come from. Yet the archive behind her name tells a different story. Born enslaved in Grenada, she had spent her childhood in bondage before being carried across the Atlantic after emancipation to live with the Burke family. By the 1850s she had lived in Britain for over a decade, moving with the family from Jersey to Cumberland, and occupying a position that defied easy classification. She was not a servant in the usual sense. The newspaper article shone some light on this ambiguity by presenting her as a social person in her own right.

The spa visit suggests something else as well. Middleton was a place of leisure, not labour. Hortense was there to walk, to rest, and to participate in a shared social rhythm. Her inclusion in the visitor list implies that she shared in the experience of the visit itself, rather than standing apart from it. In a society acutely sensitive to hierarchy, this public presentation mattered

Although this was, perhaps, a fleeting notice, it allows us to see what Hortense’s life after enslavement looked like in practice. The visit leaves no personal testimony, no letters or diaries. But in the thin column of newsprint, it records a life moving quietly, imperfectly, but unmistakably into visibility.

1871 Census

By this time, her employers Eliza BURKE, Elizabeth BURROW and her husband Edward had all died (1865, 1867 and 1863 respectively). The Burrows had no children and Elizabeth left Carleton Hall to her brother-in-law, the Reverend Joseph Ashton BURROW and Henry Edward Manning, Archbishop of Westminster. Although she had been given an annuity from William BURKE and possibly was one of the “old servants” referred to in Elizabeth’s will, Hortense may have found herself unemployed and left Carleton Hall after Elizabeth had died.

The 1871 census shows a Hortense WATSON back in Jersey lodging at Oxford Cottage, Oxford Road, St Helier when she was 52. She is listed as Unmarried. If this was her, this would add an ambiguity to her date of birth (1819) and so identity. The place of birth was given as Spain but I would imagine this could have been a confusion between Grenada and Granada.

The entry in the last column is not any of the options 1-4. It is likely to be a scheduling or clerical annotation unrelated to disability.

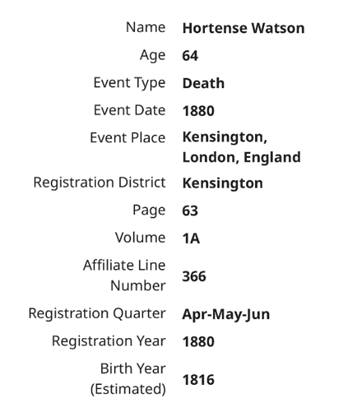

Death Record

There is a record for a Hortense WATSON who died in Kensington in 1880 age 64 which adds another date ambiguity as she would have been born in 1816. It is interesting to note that Elizabeth BURROW had also died in Kensington at 26 Argyll Road in 1867.

26 Argyll Road, Kensington is a large terraced house spread over 4,026 square feet, with a valuation of £10,552,000 in 2024.

The death record copied below is a simple statement. It also states that Hortense was born in 1816 and so conflicts with the census records which consistently indicate a date of birth of 1821.

Another look at the Slave Registers reveals another person that should be considered.

1817 Slave Register

A Hortense appeared in the 1817 slave register at the Providence estate which was owned by William BURKE. She was described as a mustevo which was a term used for someone with one African great-grandparent, making them predominantly European in appearance and, according to the prevailing standards of the time, often considered "whiter" and of higher social status than individuals with more recent African ancestry.

The term was used to determine social and legal standing, including access to rights, privileges, or, in some cases, freedom. People with lighter skin tones or more European ancestry were more likely to be freed from slavery or enjoy better working conditions.

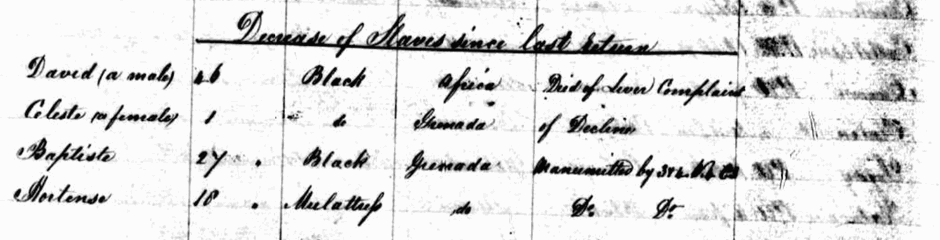

1834 Slave Register

This Hortense appeared again in the 1834 slave register aged 18 on the same estate. Described here as a mulatress which is the French term for someone with mixed African and European parentage. This showed that she was manumitted in the year leading up to 31st July 1834.

If this was indeed Hortense Watson, she would have been 25 in 1841, not 20 and all the census records in Jersey and England must have been incorrect.

So, the data on Hortense is somewhat ambiguous. Knowledge of her race, either black or mixed race, would answer the question conclusively. There are no known portraits of her or references to her race other than contained in the Slave Registers.

Jersey Black History Month

Jersey Heritage celebrated their black history in 2020 and wrote a mini biography on their Facebook page.

The Jersey Philatelic Bureau later commissioned a set of commemorative stamps with images of black figures who played a part in the island’s history. It was amazing to see that Hortense WATSON was featured in the collection. Hortense is pictured here in front of the house that she lived in.

Unfortunately, the image they used for Hortense (and possibly the others in the stamp series) was just an imaginative illustration by the artist as there are no known images of her She is pictured standing in front of Windsor Crescent where she lived in 1841. As they have depicted her as a black woman, and not mixed race, the image should reflect a young woman of 20 years old. It is hard to imagine the woman depicted in their illustration as a fitting likeness.

Summary

The life of Hortense Watson, traced through slave registers, census records, wills, and commemorative gestures, reveals a journey marked by displacement, resilience, and quiet dignity. Born enslaved in Grenada, Hortense’s trajectory from plantation life to domestic service in Jersey and Cumberland reflects not only the brutal legacies of empire but also the ambiguous intimacies forged within them. She spent her life in servitude, however, her inclusion in William Burke’s will and the spa visit in Cumberland suggests a relationship with the Burke family that transcended conventional hierarchies. Yet, the archival silences, conflicting birth dates, uncertain racial descriptors, and the absence of authentic imagery underscore how incomplete our understanding remains. Hortense’s story is emblematic of many whose lives were shaped by enslavement but rarely recorded with care or clarity. Her presence in Jersey’s Black History commemorations is a powerful act of reclamation, even as it raises questions about representation and historical fidelity.