Frederick and Mary Aberdeen

Fact File:

Claim Number: 803

Compensation Award: £34 8S 0D

Number of Enslaved in Claim: 1

Parish: St. Andrew

Parliamentary Papers: p. 99

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Life of Frederick and Mary Aberdeen

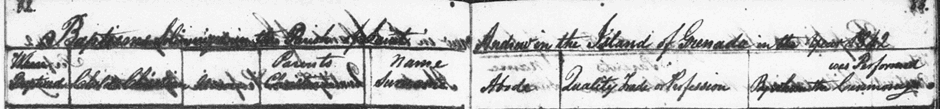

Frederick Aberdeen and his wife, Mary Angelique Aberdeen, were residents of the Providence Estate in the parish of St Andrew, Grenada. Records show that they lived on the estate during the final years of slavery and the transition into emancipation. They had a son Frederick Alexander ABERDEEN who was baptised on 12 Apr 1842 and the family were still on the estate at this time.

Frederick’s profession is listed as a mason, confirming his status as a skilled tradesman, an occupation that would have been in demand during the period of rebuilding and social transition following emancipation.

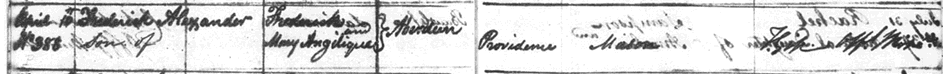

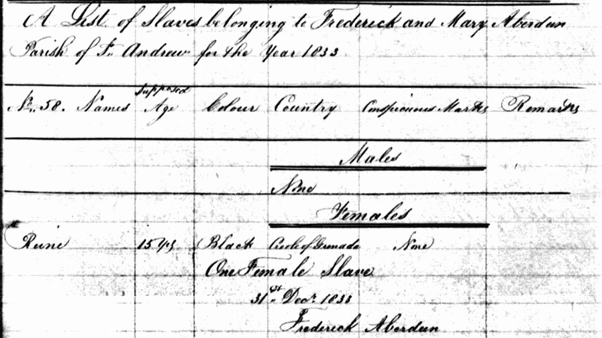

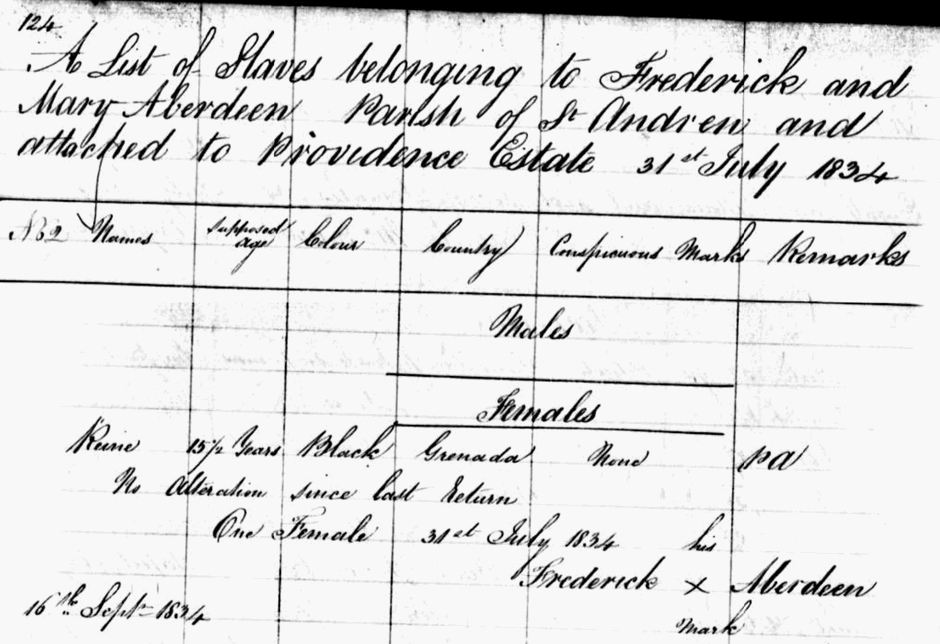

They jointly claimed compensation for the loss of their one enslaved worker called Reine who first appeared listed under their ownership in the 1833 slave register aged 15. By placing a cross for his name on the register, this suggests that Fred was illiterate.

Little else is known about the couple’s later lives although these records remind us that Grenada was not confined to large plantations but extended into households and skilled tradespeople who relied upon coerced labour.

Frederick and Mary Aberdeen’s story is therefore one of ordinary people caught up in a system that advocated enslavement and, although working class, became beneficiaries of the compensation scheme.

With little other information about the couple, we can speculate that the most likely ancestry for Frederick Aberdeen is that he was a free coloured man, likely of mixed African and European heritage. This conclusion comes from several clues in the historical record: the surname Aberdeen appears in Grenada most commonly among free coloured families rather than white planter dynasties; his occupation as a mason fits the pattern of skilled trades that were dominated by free coloured people in the early nineteenth century; and the fact that he and his wife enslaved only one young woman suggests a modest household rather than a large white-owned estate. Living on the Providence Estate rather than owning it also points to a free coloured working family rather than wealthy European-descended landowners. While we cannot be completely certain without a racial descriptor in the documents, the overall evidence strongly suggests that Frederick belonged to Grenada’s free coloured population.

Frederick’s surname was probably inherited from an earlier enslaver or estate owner bearing the name Aberdeen, and he retained the name as he entered the free coloured community. It is less likely to have come from a biological Scottish planter as there is no evidence of a large white Aberdeen planter family in St Andrew or even Grenada.

Mary Angelique Aberdeen was also most likely a free coloured woman. Her life circumstances mirror Frederick’s in ways that point toward the same ancestry: she lived with him on Providence Estate as part of a modest free household, rather than as part of the white planter class, and together they enslaved only one young girl, which was a common pattern among free coloured families who held one or two domestic servants.

Her marriage to Frederick, who himself appears strongly to have been a free coloured man, further supports this conclusion, as marriages in that period and community typically occurred within the same social and racial group. Although the records do not explicitly state her race, all contextual clues suggest that Mary Angelique was also part of Grenada’s free coloured population.

Frederick Alexander ABERDEEN (1842-)

Their son Frederick had a son with his wife, Elizabeth, born 3 May 1881 and baptised 6 days later in St. Andrew Ref

There is a birth record recording the arrival of another son between them on 11 May 1884 in St. Andrew. By this time Elizabeth is registered as Elizabeth Aberdeen which confirms that the couple were married. Ref

There are also marriage records of 3 other people born to a Frederick Aberdeen who could have been his children. Virginia (b.1871), Cornelius (b.1878) and Adrian Augustus (b.1887). There is a record that a Virginia Aberdeen had a daughter in St. Andrew in 1884. She would only have been 13 if it was the same person.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Enslaved

1833 Slave Register

The 1833 slave register shows that Frederick and Mary Aberdeen had one enslaved a girl named Reine. Reine was born in Grenada and lived on the Providence Estate in St. Andrew, where she was probably born.

1834 Slave Register

In the 1834 Slave Register, Reine was recorded as 15½ years old, still in their possession, and she remained with Frederick and Mary through the abolition period.

Reine was the only enslaved person in the Aberdeen household, which strongly suggests that her daily life was centred on domestic work: assisting Mary with cooking, laundry, cleaning, and other household duties, as well as running errands. In households that enslaved just one girl, the work was constant and wide-ranging, and girls like Reine were expected to be ever-present, obedient and industrious.

Her presence in the Aberdeens’ home also reflects the social structure of the time. Free coloured families of modest means frequently owned one or two enslaved people, often young girls whose labour provided essential support to the household. Reine’s life would therefore have been intimately entangled with the Aberdeens’ daily routines, expectations and demands.

Although the historical record does not tell us what became of her after 1834, her youth at the moment of abolition meant she would enter adulthood carrying the experiences of enslavement but with the possibility of shaping her own life in freedom.

That said, It is quite likely that Reine remained with the Aberdeens for at least a short period after emancipation, until she was old enough to establish her own household or employment. There is no record of her own family so there may have been no other option but to stay.

It is possible that she was not much younger than Mary Aberdeen who had Frederick Augustus Aberdeen in 1842. The Aberdeens were not wealthy and their limited means suggests they were unlikely to have suddenly employed another servant, making Reine’s continued presence valuable to them. Reine may have stayed on to support Mary as she was bringing up her family. This would have given Reine stability, familiarity, and shelter while she navigated early adulthood in a changing society.

Reine’s story is a reminder that emancipation was lived not only on large plantations but also within small households, where the lives of young enslaved girls were tightly controlled yet often overlooked in official histories. Reine’s presence in the Aberdeens’ home illuminates both the vulnerability of enslaved children and the resilience required to navigate a world marked by inequality, coercion and profound change.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. John Angus Martin of the Grenada Genealogical and Historical Society Facebook group for his editorial support and Owen Hankey for content contributions.